In early January 2026, US forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. The US is taking control of Venezuela’s oil sector while US oil companies invest to revive output. A state can possess vast reserves and still be commercially isolated if buyers cannot pay, insurers cannot cover voyages, or companies cannot deploy equipment without sanction exposure. In that sense, “takeover” is shorthand for a possible regime shift in how contracts are honored, how exports are authorized, and how sanctions are applied or removed.

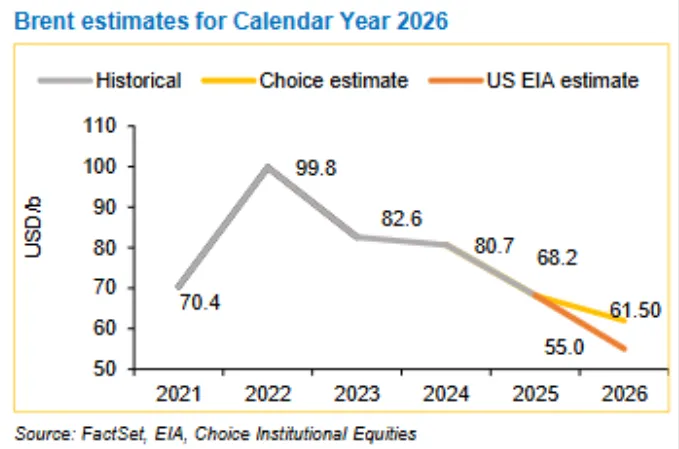

For global oil, the immediate question is not “How much oil sits underground?” but “How much oil can be produced, sold, shipped, and paid for without triggering sanctions risk?” Venezuela’s barrels have been constrained for years by sanctions and by degraded infrastructure. It raises the probability of sanctions recalibration and the return of capital and technology.

For India, the starting point is counterintuitive: even a major political rupture in Venezuela does not automatically shake India’s near-term oil balance because Venezuelan crude had already shrunk to a marginal slice of India’s import basket. What changes is the medium-term impact of discounted heavy crude becomes more plausible again, and stranded Indian upstream value in Venezuela becomes more recoverable if restrictions ease.

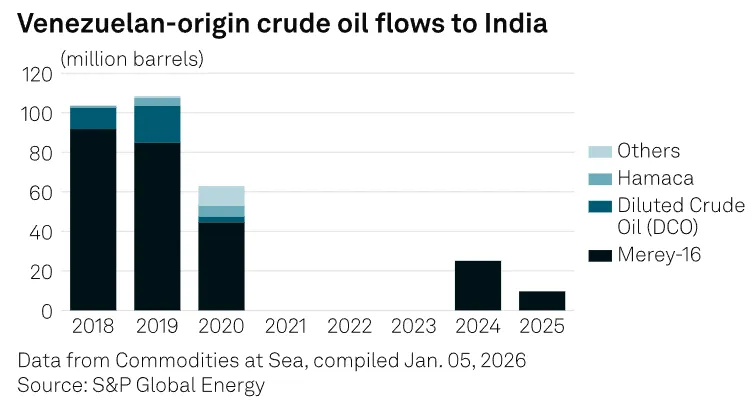

India imported 108 million barrels of Venezuelan-origin crude in 2019 (around 300,000 b/d), but this fell to 25 million barrels in 2024, and only one VLCC discharged Venezuelan crude at Sikka in 2025. When flows have already “largely dried up,” a political rupture, even one involving control claims does not mechanically remove a major stream from India’s ports.

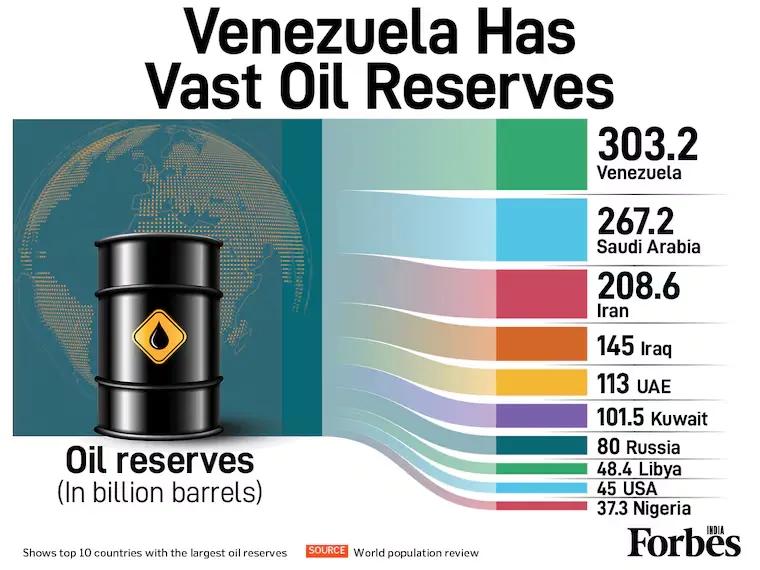

Venezuela’s oil story is built on a paradox: immense reserves alongside chronic underproduction. Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves at 303.2 billion barrels, about a 20% global share yet decaying infrastructure and political upheaval have stalled production.However, abundance is not the same as supply to market.

Because Venezuela currently accounts for less than 1% of global production, the takeover’s immediate global impact is likely to be more about expectations and trade routes than about physical shortages or surpluses. Venezuela has the world’s largest reserves but “accounts for less than 1 per cent of global production,” framing the event as a potential inflection point rather than an immediate supply shock.

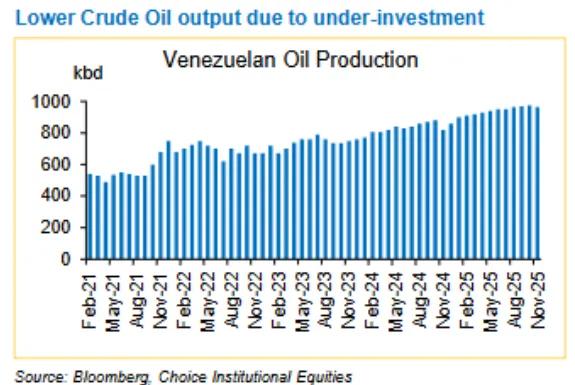

Production numbers show how far Venezuela has fallen from its own history. Venezuela’s oil production declined from 3 million b/d in January 2008 to about 963,000 b/d in December 2026. The combined picture is a country oscillating around the one-million-bpd mark, far below prior peaks, and vulnerable to further political shocks.

Crucially, even optimistic scenarios are described as slow. Meaningfully increasing Venezuela’s production would take “years and billions of dollars” in investment. It suggests a gradual easing of supply tightness rather than a sudden flood that resets oil prices.

Venezuelan grades that India historically bought such as Merey-16 and Hamaca are described as typically heavy, with high sulfur and high asphaltene content, producing a higher % of residue. This dictates which refineries can process the crude and how much incremental value they can extract without costly adjustments.

From refining operations perspective, Merey is “very heavy” with high acidity levels, and Indian refineries are not designed to process it “neat” without large-scale blending facilities. Some complex refineries have experimented by mixing it with lighter oils, but larger benefits from discounted Venezuelan crude would require “significant investments” in plant configurations. This is why a return of Venezuelan crude helps only a subset of Indian assets.

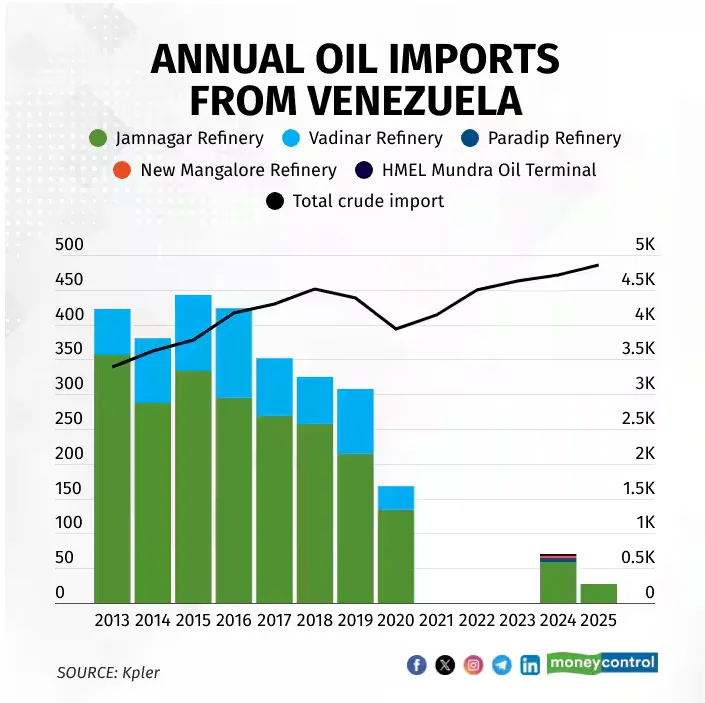

There are only a few refineries in India that can process Venezuelan crude at scale, with Jamnagar as “the only major refinery” that can do it, while sustained processing has historically concentrated at Reliance’s Jamnagar and Nayara’s Vadinar. The takeaway is that Venezuela’s crude may be cheap, but it is selectively cheap. Its discount is partly compensation for processing difficulty and limited refinery eligibility.

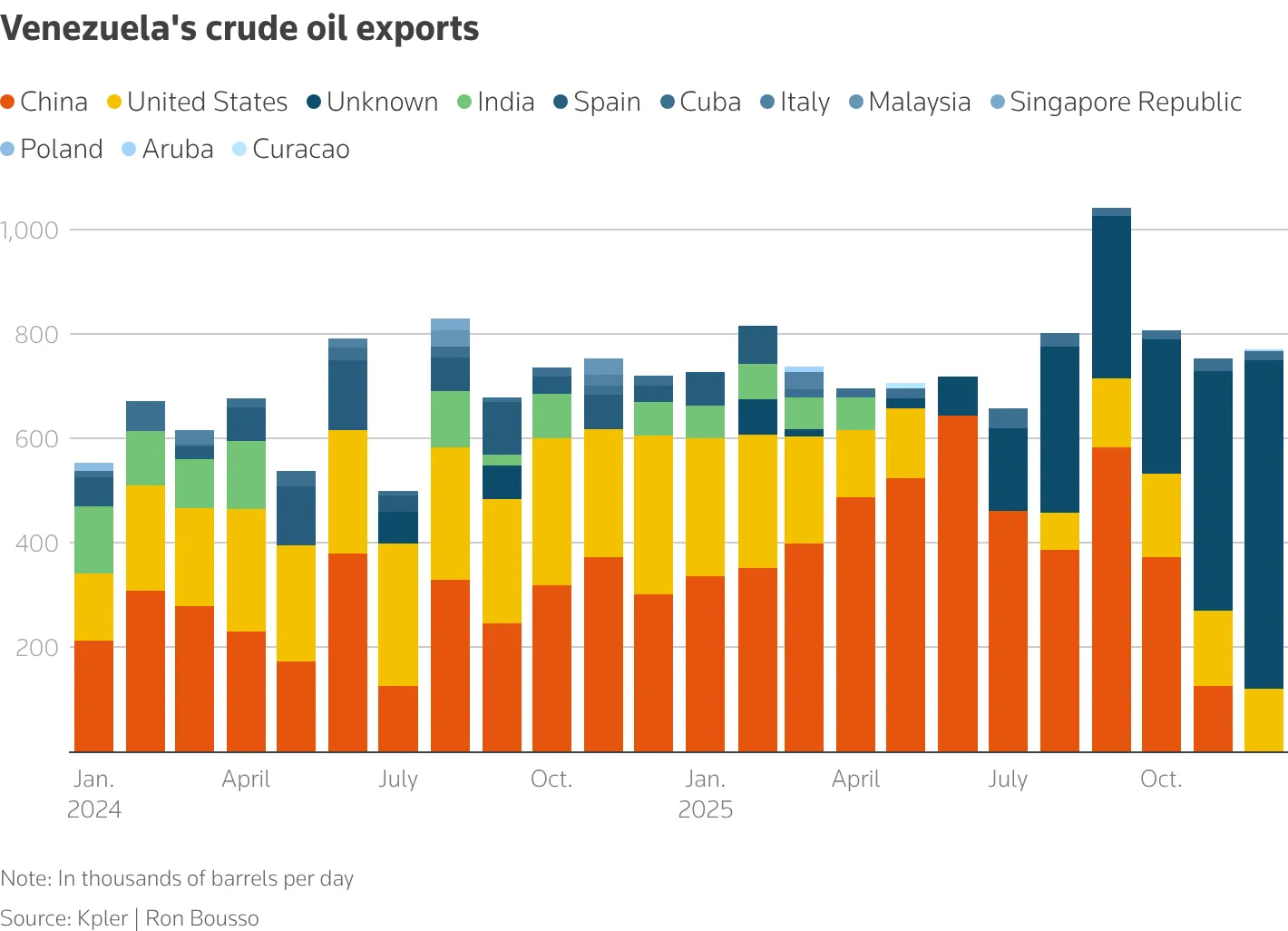

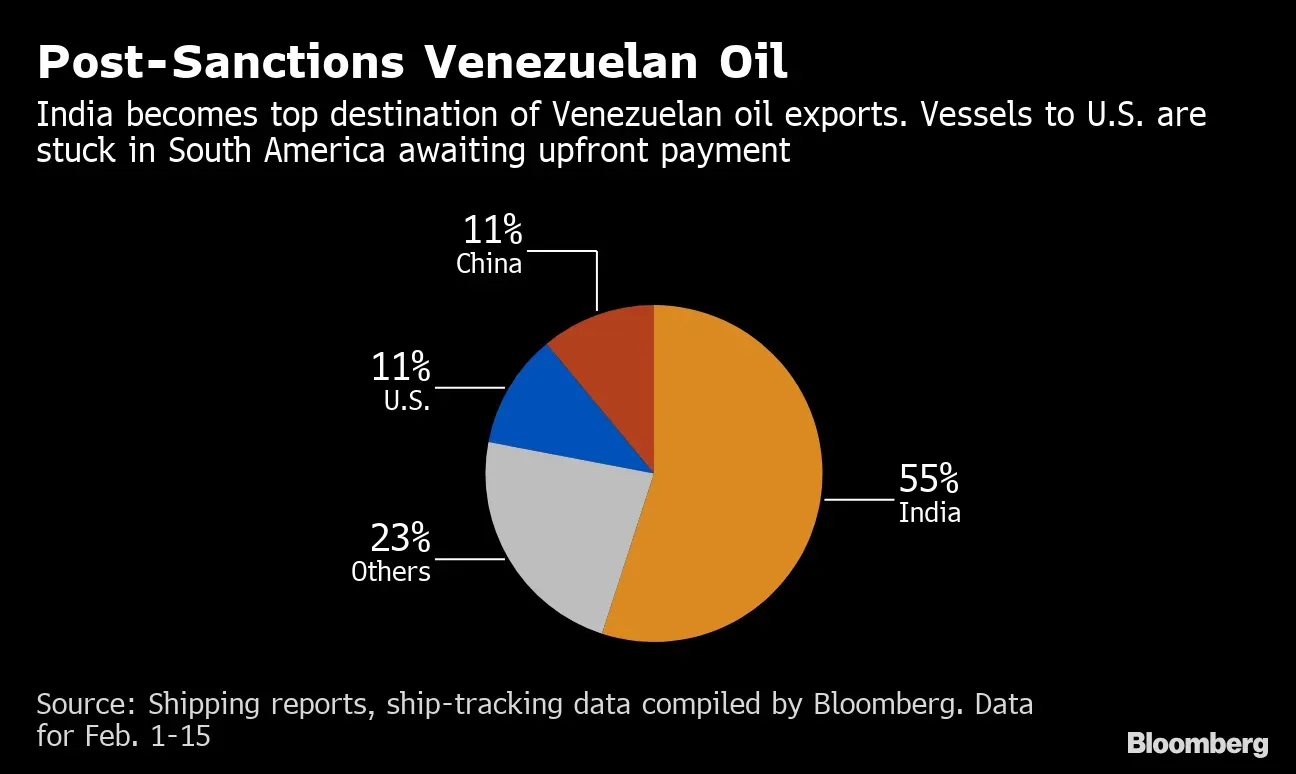

A US-driven redirection of Venezuela’s crude exports would hit China first because Beijing became the main outlet after US sanctions were imposed in 2019: China took more than half of Venezuela’s 768,000 bpd of crude exports last year, with roughly two-thirds of those barrels going to independent “teapot” refineries willing to buy at deep discounts that compensate for sanctions risk.

If sanctions are lifted under a US-backed setup, that discount disappears because the oil would trade closer to international prices, weakening teapots’ incentive to keep buying; meanwhile, about one-third of Venezuela’s China-bound flows currently serve debt repayment to Beijing, a channel that could also be disrupted because such barrels are likely priced near production cost rather than market value. With the US Gulf Coast a more natural destination for Venezuela’s heavy crude due to proximity and lower freight, Reuters estimates that diverting much of the teapot-directed stream could lift US imports by more than 200,000 bpd within months, more than doubling recent US purchases based on 2025 export levels turning China’s bargain supply into America’s refining advantage.

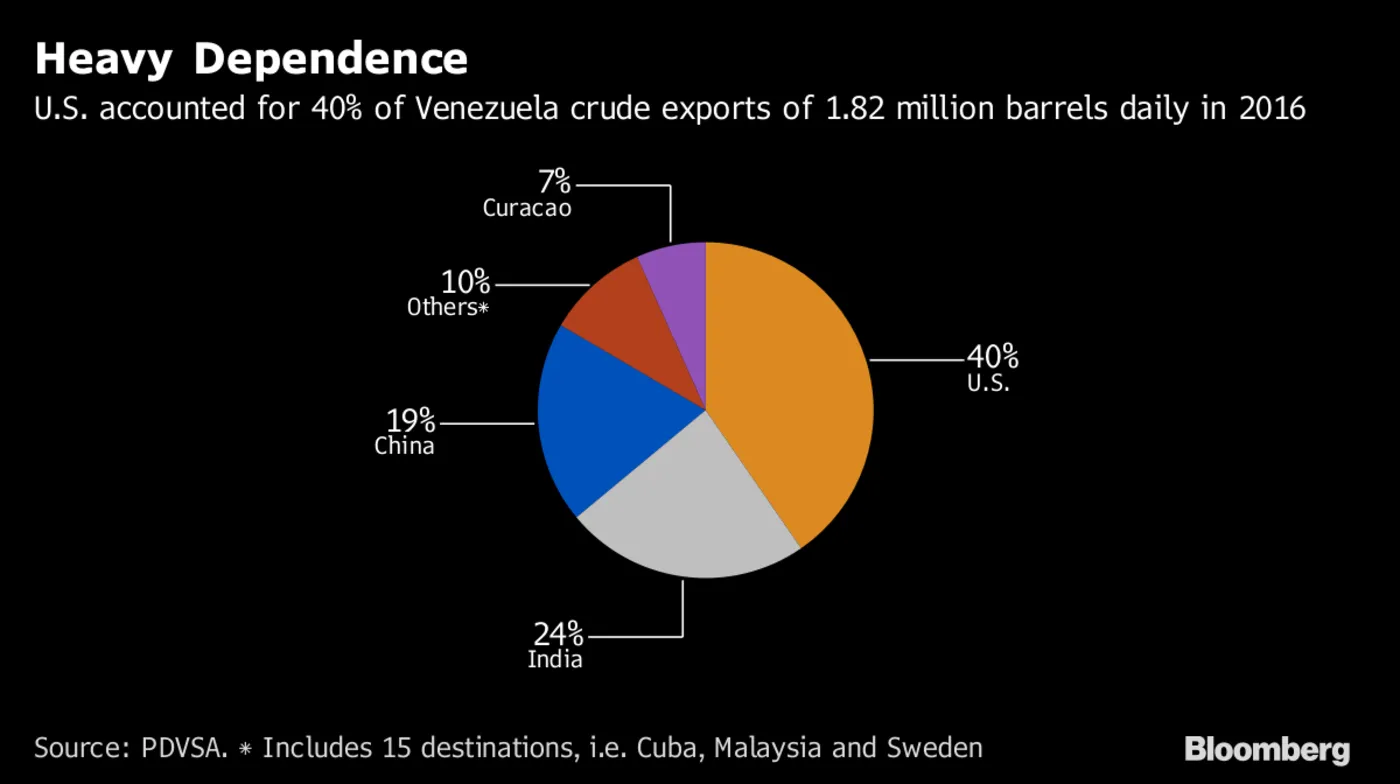

A stable, US-aligned transition in Caracas would likely “re-route” Venezuelan crude back toward the United States because Gulf Coast refineries are built to run heavy sour barrels and still need heavy grades to optimize yields of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel even after the shale boom made the US crude mix lighter. Historically, that pull was enormous, as was the US's dependence on oil from Venezuela.

Trade reallocation is already visible in the way Venezuelan crude moves under carve-outs and licences. The “cheapest crude available to India” became reachable again after the US reimposed restrictions, because exceptions and licences can still enable limited flows. That mechanism restricted regime plus selective permissions naturally favors the most capable refiners and the most compliant channels.

This matters globally because it implies that Venezuela’s barrels, when available, do not simply “add supply” in a neutral way; they shift bargaining power and discounts across regions depending on who can buy legally and process the grades efficiently.

The most practical lever in all this is the sanctions policy, because it governs whether oil trade is merely cheap or actually usable. US sanctions extending from 2019, with curbs lifted twice: first in October 2023 for a six-month period with conditions, then reimposed in mid-April 2024 after Maduro allegedly violated terms while allowing exceptions for firms such as Chevron, Repsol, and Maurel & Prom. Reliance also obtained a licence under these exceptions.

Imports to India peaked at $7.2 billion in FY2019, but the relationship faded as sanctions-driven compliance and payment risks grew; imports fell to zero in FY2022 and FY2023 despite technical compatibility with Indian complex refineries. When Washington partially eased sanctions in late 2023, imports revived to $802 million in FY2024 and $1.41 billion in FY2025, with Venezuela’s share edging back to about 1% before weakening again.

The hard data shows why India is unlikely to face an immediate problem. cites that in 2025 Venezuela’s share of India’s crude oil imports was merely 0.6%, averaging 28,000 bpd, compared with a 12.4% share in 2013 before sanctions-driven declines. When a supplier is already that small, a crisis there is not the same as a crisis in a dominant source.

At the same time, history shows Venezuela can be large for India under normal conditions. India’s purchases of Venezuelan oil peaked at 441,000 bpd in 2015, around 12% of crude imports that year, with Reliance accounting for 75% and Nayara for the rest. India imported 108 million barrels in 2019, around 300,000 b/d, before flows collapsed. These figures establish that Venezuela is not structurally irrelevant to India; it has simply been politically and commercially constrained.

Venezuelan crude offers India a “politically acceptable diversification option” amid American pressure on India’s Russian oil imports, while also warning that intake is constrained because only a handful of Indian refineries can process very heavy grades on a sustained basis.

If Venezuelan crude returns in meaningful volumes, the immediate payoff for India is refining margin support rather than some broad-based macro miracle. Merey averaged $68 a barrel in June and was $14 a barrel cheaper than discounted Russian barrels and $20 cheaper than Saudi and US grades, according to customs data. It also quantifies the scale effect: replicating a past peak of roughly 450,000 bpd of Venezuelan oil could save India more than $3 billion at current prices, and one month’s substitution could have cost $75 million more using an alternative Russian grade.

The price paid for Venezuelan crude in FY25 was $496/tonne versus an average of $586/tonne, described as “one of the lowest.” The point is not just that Venezuelan crude can be discounted; it is that the discount can be large enough to influence procurement decisions even when logistics are long and crude quality is difficult.

But constraints keep this opportunity from becoming system-wide. stresses only a few refineries can process these high-sulphur heavy grades at scale, and warns that without blending facilities and configuration investments, running Merey “neat” is not feasible for most units. That means the gains accrue disproportionately to the most complex refineries especially Jamnagar and Vadinar rather than to India’s entire refining fleet.

Bilateral trade between India and Venezuela fell from over $7.3 billion in FY19 to just over $1.6 billion in FY25, while imports peaking at $7.2 billion in FY2019 and reviving to $1.41 billion in FY2025 before slipping to $255 million in April–October 2025 (FY2026 to date), with Venezuela falling to 18th among suppliers. Those numbers show that a sanctions reset could reshape not just oil flows but the broader commercial relationship.

The first driver is policy clarity: whether “control” translates into a workable sanctions framework that banks, shippers, and refiners can rely on. Multiple sources converge on the idea that the near term is constrained and the medium term is where change happens, uses a one-to-three-year near-term window, and the development as “more structural than immediate,” contingent on sanctions policy and the pace of production recovery.

The second driver is the speed of operational recovery. Venezuela’s production has fallen dramatically from historical levels, and rebuilding is described as requiring years and billions of dollars. Even if US oil companies invest, the market impact will likely come in increments, with early gains limited by infrastructure repair, field rehabilitation, and the technical challenges of producing and upgrading heavy crude.

The third driver is India’s ability to convert cheap crude into cheap products at scale. The upside is real discounts in the range of $14–$20 per barrel versus alternatives, and FY25 pricing that is materially below average per tonne, but so is the bottleneck of refinery configuration and blending. If India’s complex refiners scale their ability to handle Venezuelan grades, the country gains both economically and geopolitically, widening its procurement choices while keeping exposure to compliance risk under tighter control. If not, Venezuela remains an episodic, opportunistic barrel which is valuable, but not transformative.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart