by Siddharth Singh Bhaisora

Published On Feb. 7, 2026

India’s FY27 Union Budget is supporting growth while keeping the fiscal framework credible in a more uncertain global environment. One of the important measures for the government has been to reduce the fiscal deficit. Let’s understand what that is first.

A fiscal deficit is the gap between what a government spends in a year and what it earns from taxes and other income. If spending is higher than income, the government has a deficit and usually covers it by borrowing money (for example, by issuing bonds). It’s shown as a percentage of GDP to indicate how large the gap is relative to the size of the economy.

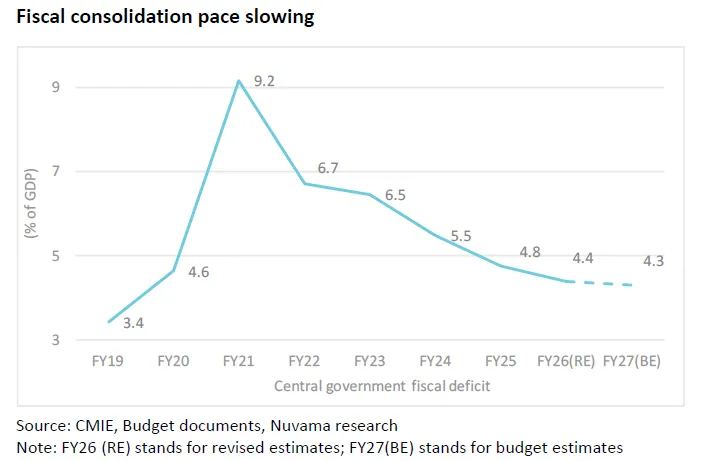

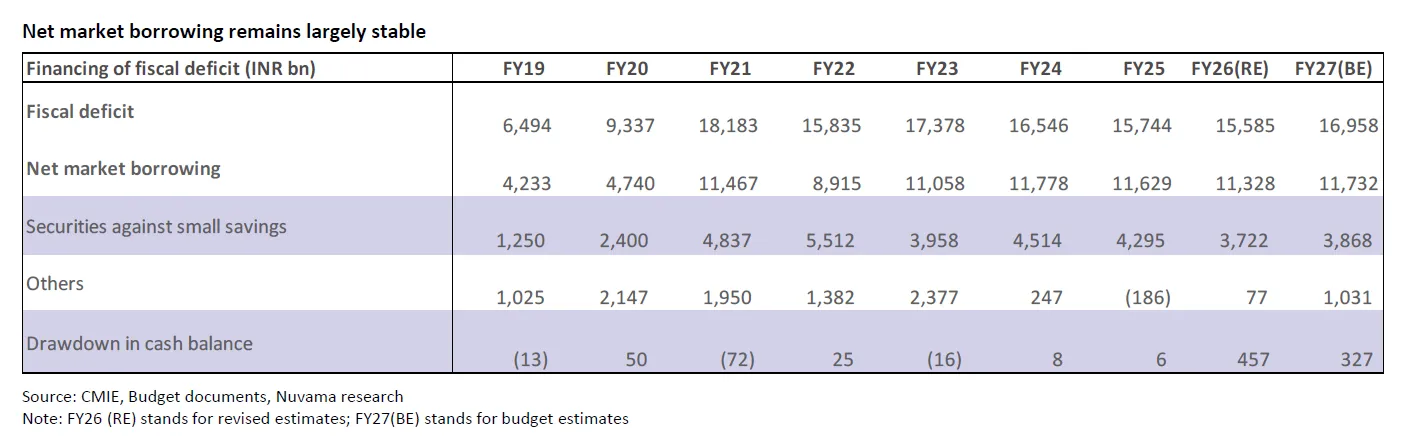

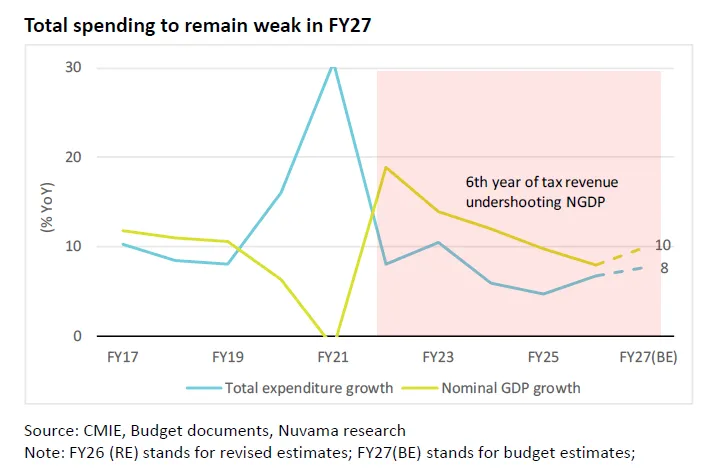

So, this budget is targeting a gross fiscal deficit of 4.3% of GDP in FY27, compared with 4.4% in FY26. The consolidation is now slower than in the earlier post-pandemic years, when the deficit fell sharply from elevated levels and government spending repeatedly undershot nominal GDP growth.

A key part of the fiscal stance is the interaction between deficit reduction and the removal of the GST compensation cess (about 0.2% of GDP impact for FY27). Together, the budget implies a neutral fiscal impulse, versus the negative impulse that has prevailed for multiple years.

This is what “fiscal drag ending” means in practice: government policy stops acting as a persistent headwind to growth and becomes more neutral, even without a large deficit expansion.

The deficit target matters because it anchors market expectations for borrowing, interest rates, and medium-term debt sustainability. A 4.3% deficit is not loose by India’s recent standards, but it signals that the government is prioritizing growth support through composition and steady spending rather than accelerating deficit compression.

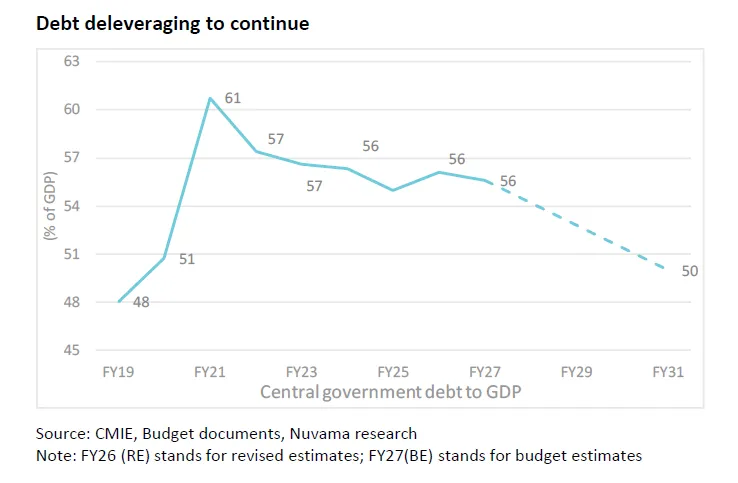

The budget reiterates the medium-term debt objective: bringing central government debt to around 50% of GDP (±1%) by FY31, from 56.1% in FY26. This is an important commitment because it frames how much room the government believes it has to support growth while still converging to a lower debt ratio over time.

Credibility is ultimately about whether the numbers add up. In FY26, the government reportedly met the deficit target despite a revenue shortfall of roughly INR 900bn, helped by slower-than-budgeted spending (including lower capital spending by about INR 250bn). FY27 builds on that with a manageable deficit path, conservative-to-plausible revenue growth assumptions, and controlled expenditure growth that remains below nominal GDP growth.

Neutral impulse means the government is no longer tightening fiscal policy in a way that mechanically subtracts from growth. For an economy where public investment and targeted transfers can influence demand conditions, moving from consistent tightening to neutral can lift the baseline growth outlook, especially when private investment is sensitive to demand visibility.

It also matters for the policy mix. If fiscal policy is less restrictive, monetary policy does not have to work as hard to stabilize growth, which can reduce the risk of a growth-inflation tradeoff. That can influence bond yields, credit conditions, and corporate earnings expectations, even if headline deficit improvement is small.

Finally, neutral fiscal impulse reduces the chance that growth support relies entirely on one lever, typically central bank easing. A more balanced mix helps when external conditions such as commodity prices, global growth, and financial volatility are less predictable.

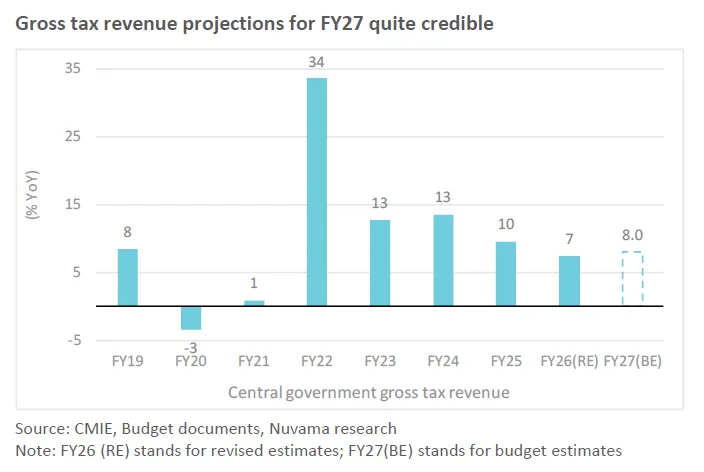

The revenue side is anchored by a moderate recovery in tax collections, without assuming a return to the very high buoyancy seen immediately after the pandemic. The budget expects gross tax revenue to rise 8% YoY in FY27, versus 7.4% YoY in FY26. In absolute terms, revenue is budgeted around INR 44.0tn in FY27.

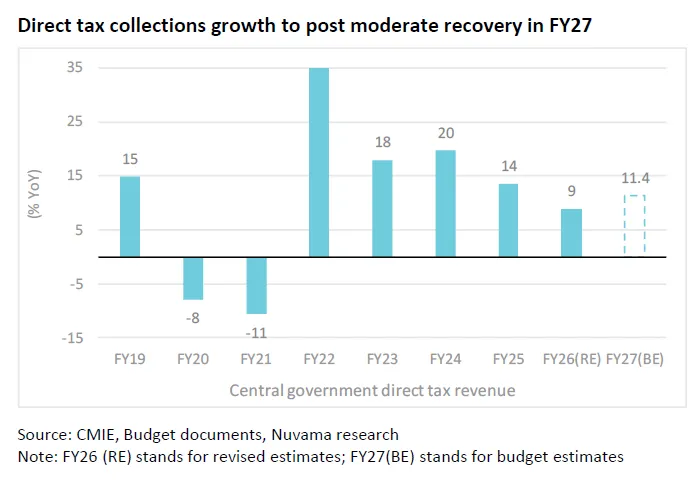

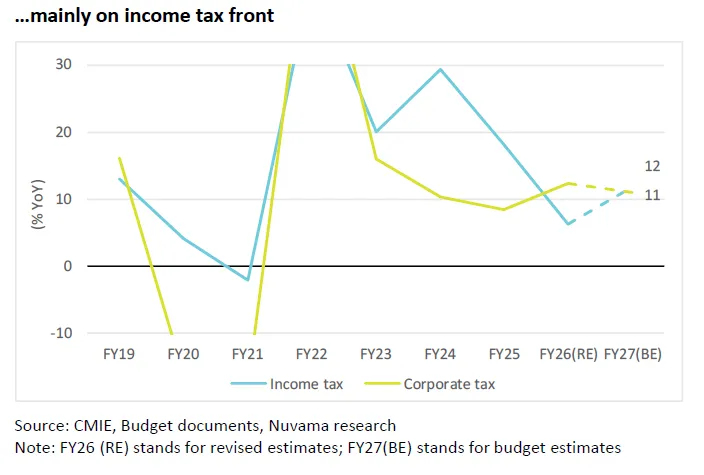

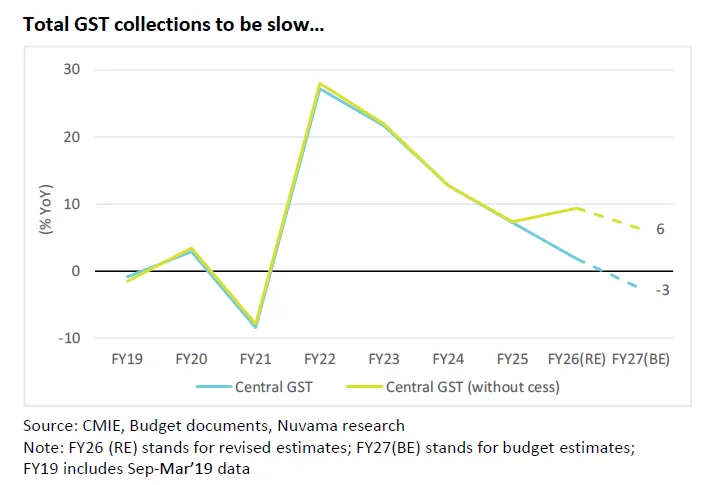

That revenue is supported by a stronger direct tax profile and a softer GST profile, largely reflecting policy changes rather than a collapse in the tax base. Direct taxes (corporate and personal combined) are projected to grow 11.4% YoY in FY27, while total GST is budgeted to contract (about -3% YoY) because of cess changes and tax cuts flowing through.

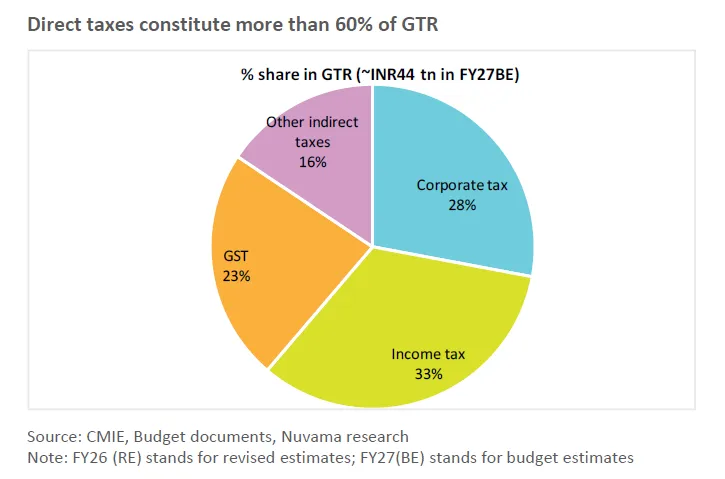

A notable structural point is the composition of tax revenues. Direct taxes are estimated to account for more than 60% of GTR, with shares around 33% income tax and 28% corporate tax, while GST contributes about 23% and other indirect taxes about 16%. This mix matters because direct taxes tend to track income and profits more closely, while indirect taxes are more sensitive to consumption volumes, trade flows, and policy rates.

In FY26, direct tax growth slowed to sub-10% levels, partly due to weaker income tax collections linked to tax cuts. FY27 assumes a return to 11–12% growth in direct taxes, framed as credible in an environment with no major new tax shocks and nominal GDP expected to improve.

If nominal GDP growth is around 10% (the budget framework implies this order of magnitude), then direct tax growth of 11–12% is a mild buoyancy assumption rather than an aggressive one. The key risk is the macro cycle. If profits compress or income growth slows, direct taxes could surprise on the downside.

At the same time, the reliance on direct taxes can be a stabilizer if consumption remains uneven, because income tax collections can hold up better than GST in certain conditions—especially when formalization and compliance trends continue.

GST is budgeted to contract in FY27, primarily reflecting the dissolution/removal of cess and the impact of earlier tax changes. This is an important distinction: weakness in GST here is not automatically a signal of demand collapse, but a reflection of how collections are recorded after policy shifts.

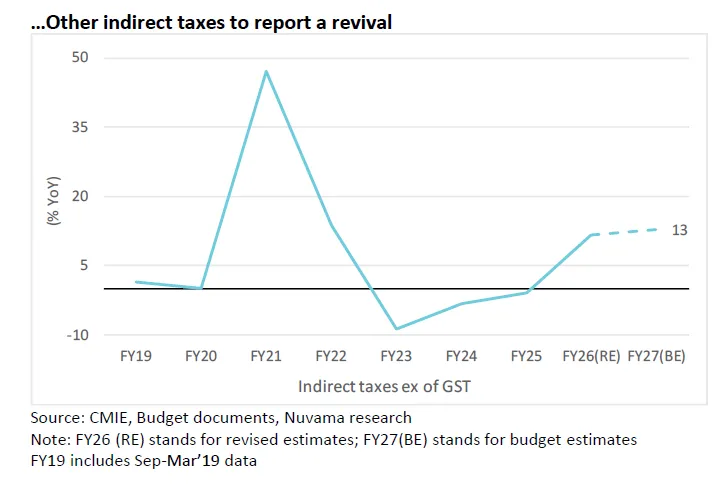

Other indirect taxes such as customs and excise components outside GST are budgeted to grow strongly (around low-double digits in the framework). That offsets part of the GST softness and helps keep total indirect tax growth positive.

The broader macro takeaway is that the government is not leaning heavily on a rebound in indirect tax buoyancy to make the numbers work. That reduces the risk of a large revenue gap if consumption growth remains modest.

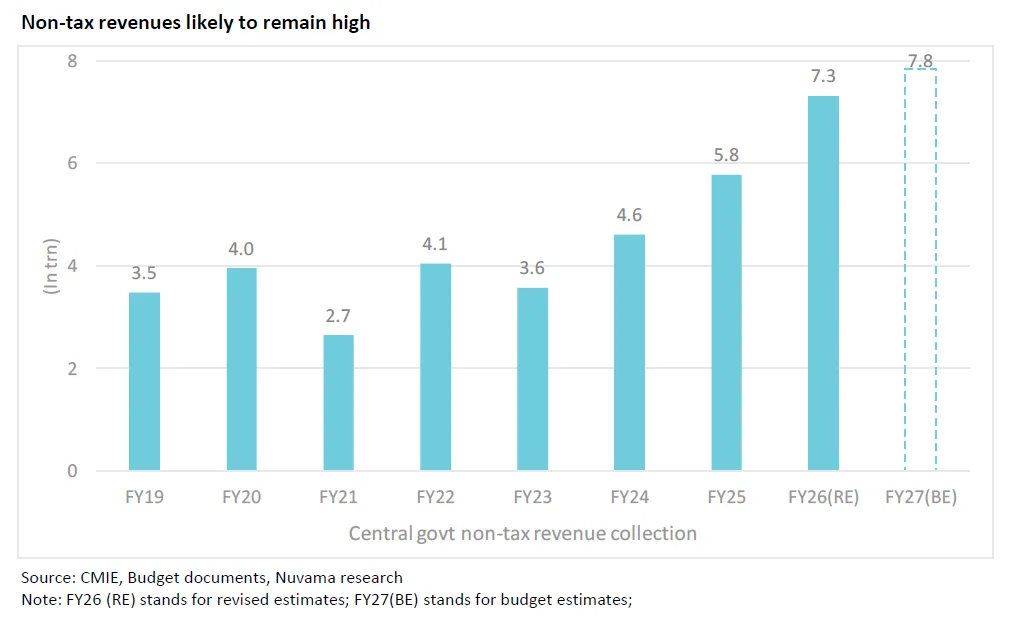

Non-tax revenue is budgeted at about INR 7.8tn in FY27, growing around 7% YoY after a sharp FY26 increase supported by higher central bank dividends. The FY27 profile assumes moderation in dividend-led upside and places more weight on disinvestment receipts.

This can be constructive if asset sales are executed cleanly and market conditions are supportive, but it is not fully within the government’s control. If disinvestment receipts fall short, the adjustment typically occurs through expenditure restraint or higher borrowing.

The budget’s overall credibility improves when tax assumptions remain moderate, and even if non-tax receipts are volatile, the revenue is less dependent on a single optimistic factor.

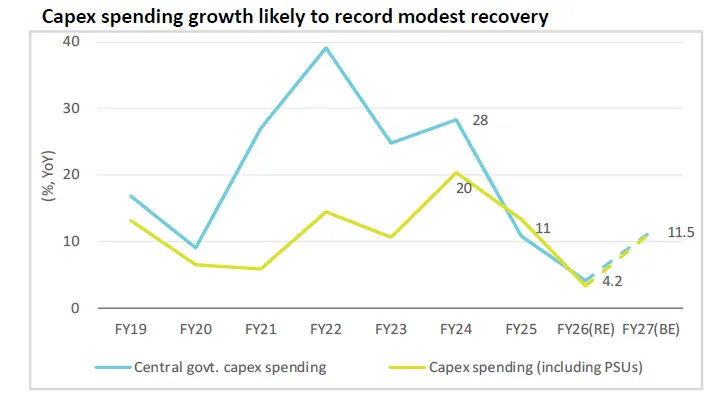

Total expenditure is budgeted at about INR 53.5tn in FY27, up 7.7% YoY from FY26 revised levels. Revenue expenditure is budgeted to grow 6.6% YoY, while capital expenditure is budgeted to rise 11.5% YoY to about INR 12.2tn. This will be the 6th year of tax revenue undershooting nominal GDP growth.

The government is keeping overall spending growth controlled, but prioritizes capex because it supports medium-term productivity and crowds in private investment. It also reflects a political-economy trade-off where capex is easier to defend under a fiscal prudence narrative than large recurring revenue expansions.

However, the distribution within expenditure categories points to constraints. Interest payments are budgeted at about INR 14.0tn in FY27, rising roughly 10.2% YoY. That is a large fixed charge and limits the flexibility of discretionary spending.

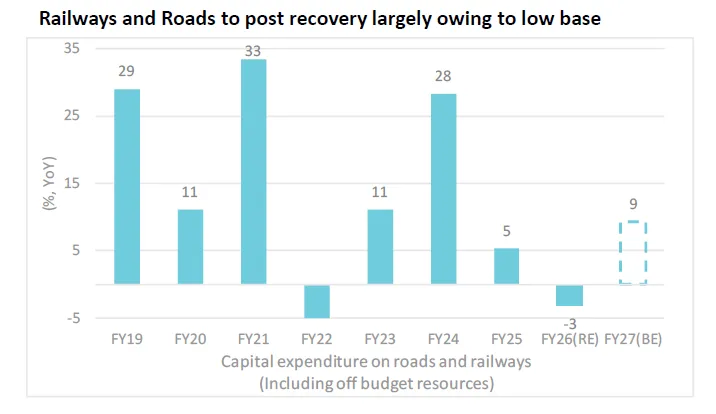

Capex had slowed sharply in FY26 (low single-digit growth), with roads and railways under pressure. FY27 aims for a revival driven significantly by defence. Defence capital expenditure is budgeted at about INR 2.3tn, up roughly 17% YoY.

By contrast, the growth profile for roads and railways is more moderate, and metro allocations appear softer. That suggests the budget’s “big push” is less about broad-based infrastructure acceleration and more about selective emphasis.

This matters for industrial activity and order books: defence-related manufacturing, electronics, and high-spec engineering can see stronger demand, while broad construction-linked impulses depend more on how effectively road and rail capex is executed through the year.

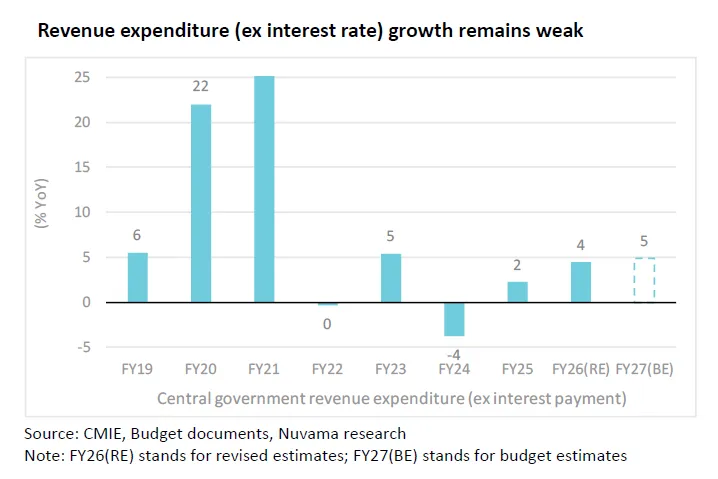

Revenue expenditure excluding interest is budgeted to remain restrained, with growth around mid-single digits to high-single digits depending on the sub-head. Subsidies are expected to remain broadly stable around INR 4.3–4.5tn, with FY27 budgeted subsidies slightly lower than FY26 revised levels.

Wages and pensions are budgeted to grow only about 4% YoY in FY27, a sharp slowdown from prior years. This can reflect either restraint or timing, if a pay commission cycle is expected later, allocations may shift into subsequent budgets.

A key macro implication is demand composition. When revenue spending remains weak (especially transfers and household-facing expenditure), consumption recovery can be uneven even if investment improves. That becomes relevant for sectors tied to mass demand.

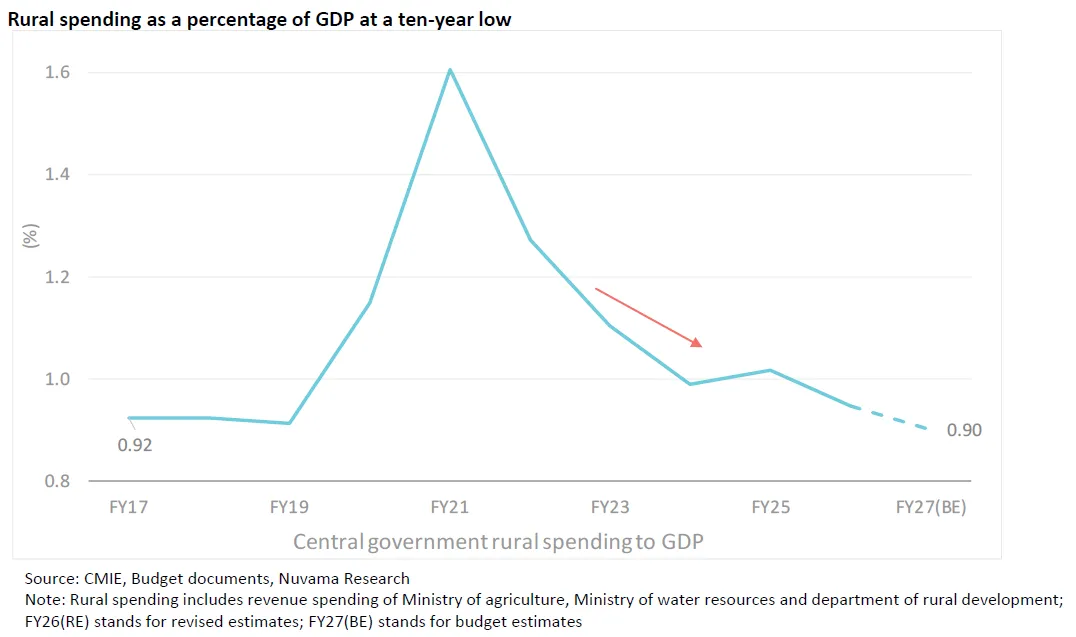

Rural spending is budgeted to rise about 5% YoY in FY27 after being flat in FY26, but its share of GDP is described as below 1% and near a multi-year low. This implies rural demand tailwinds may remain limited unless execution exceeds conservative assumptions.

Social sector spending is budgeted to jump sharply (around 40–50% versus FY26 revised estimates in certain aggregates), but recent years show a pattern of under-spending relative to budgeted levels, with shortfalls around INR 1tn in each of the last two years in the referenced framework. The headline allocations are supportive for sentiment, but the realized demand impulse depends on actual disbursement and implementation capacity through the year.

Sector impacts will depend on the capex mix, execution quality, and the extent to which revenue spending translates into realized household demand. The budget’s most direct demand impulses appear in defence capex, selected infrastructure lines, and certain targeted schemes such as EV-related incentives, electronics components, data centers, and healthcare/pharma initiatives.

Market-facing measures such as the STT hike are sector-specific by design, and their impact is more about volumes and sentiment than broad macro demand. Meanwhile, rural and social allocations look supportive on paper, but the historical pattern of under-spending means investors and operators will watch quarterly execution rather than budget speeches.

Defence Sector

Defence capital allocation is budgeted around INR 2.3tn, up roughly 17% YoY, reinforcing an ongoing modernization and procurement cycle.

This is supportive for defence electronics, platforms, and high-spec engineering supply chains, with a stronger medium-term order visibility bias than many other capex categories.

Execution pace and import substitution content will determine how much of the spend accrues to domestic manufacturers versus global suppliers.

Infrastructure Sector (roads, railways, metro)

Overall public capex is budgeted to rise (capex about INR 12.2tn, +11.5% YoY), but the mix looks uneven across sub-sectors.

Railways outlay is higher (around INR 2.93tn, +11% YoY), generally supportive for rolling stock, components, and EPC segments tied to rail.

Roads growth is positive but more moderate (around 8–9% in the referenced framework), and metro allocations appear softer, implying a more selective infrastructure impulse.

Capital markets and exchanges

STT collections are projected at INR 740bn in FY27 vs ~INR 640bn in FY26, with higher rates especially on derivatives.

The first-order impact is lower industry volumes and weaker sentiment for transaction-driven businesses, particularly in high-turnover derivatives.

Over time, outcomes depend on whether activity migrates to alternative instruments or compresses structurally.

Autos and EV ecosystem

The PLI outlay for auto and components is raised sharply in the sector notes (a multi-fold increase in the referenced budget summary), signaling continued policy support for EV localization.

EV-related scheme allocations (including e-drive) and electric bus deployment announcements are supportive for selected OEMs, charging infrastructure, and component suppliers.

The net demand effect depends on state-level execution, procurement pipelines, and financing availability for fleet operators.

Electronics manufacturing and components

The broader PLI/ECMS ecosystem remains supported, but aggregate PLI growth is described as moderating (cumulative allocation since inception noted around INR 460bn).

Incremental support appears more focused on components depth and supply-chain resilience rather than only final assembly.

For companies, the key variable is approval and disbursement timing rather than headline outlay.

Power and new energy

Several measures support energy transition themes: rooftop solar outlays rise, and customs duty changes on specific inputs can reduce project costs in parts of the supply chain.

A multi-year INR 200bn outlay for carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) across five sectors is notable for long-gestation industrial decarbonization pathways.

The near-term impact is likely more capex planning and pilot activity than immediate earnings, with clearer benefits for EPC, equipment, and select developers over time.

Pharma and healthcare services

A planned INR 100bn allocation over five years for biologics/biosimilars ecosystem, education/research institutes, and a large clinical trials network is supportive for long-term capability building.

Healthcare initiatives around medical hubs and workforce training can expand capacity and improve services depth, but execution determines speed of impact.

Import duty changes for select medicines can shift product economics at the margin, but the strategic move is toward standards, R&D, and trial infrastructure.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart