by Siddharth Singh Bhaisora

Published On Jan. 16, 2026

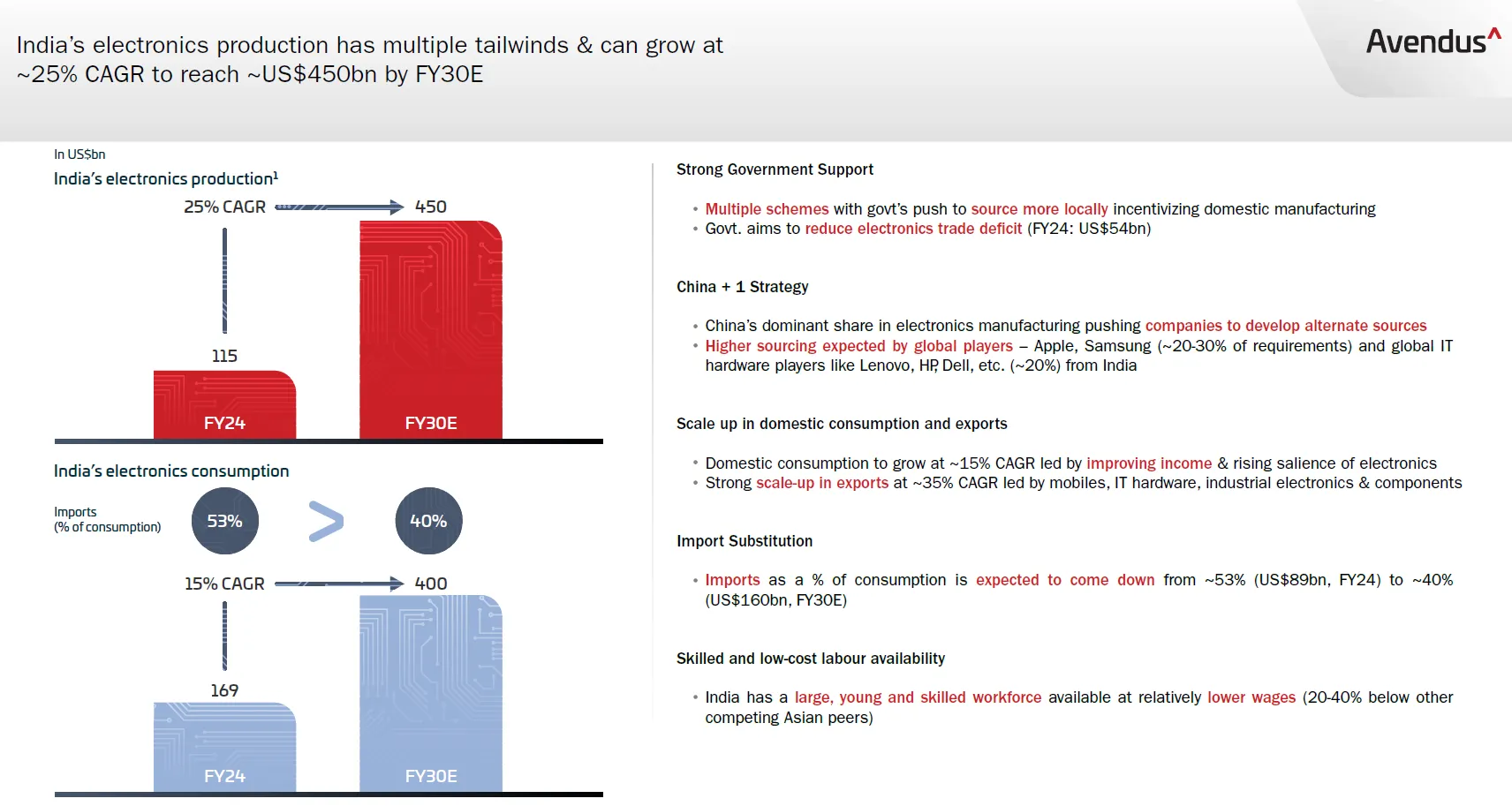

India’s electronics story looks like a triumph on the surface. Output has scaled, exports have surged, and global brands now treat India as a real manufacturing base rather than a “someday” option.

Government releases point to electronics exports rising eightfold from ₹38,000 crore in 2014–15 to ₹3.26 lakh crore in 2024–25, while electronics production climbed sharply over the same decade. Mobile phone exports are growing to the point where they’re now among India’s largest export categories, with smartphone exports hitting $13.1 billion in April–November 2024.

And yet the EMS (electronics manufacturing services) industry, the factory layer that turns designs into shipped products, feels stuck. EMS in India has expanded in volume faster than it has expanded in capability. The country is getting better at assembling finished goods, but far less successful at capturing the value that sits upstream in components, engineering, process IP, and design ownership.

Even as India aims for a much larger electronics manufacturing base over the next decade, the current shape of the ecosystem keeps EMS companies squeezed between customer power and imported dependency.

Net margins are structurally thin, often in the low single digits; working capital is a constant choke point; and the biggest growth tailwind of the last few years, PLI has been unusually concentrated and inherently temporary.

What follows is the case for why Indian EMS is stuck and what it would take to break out of the middle.

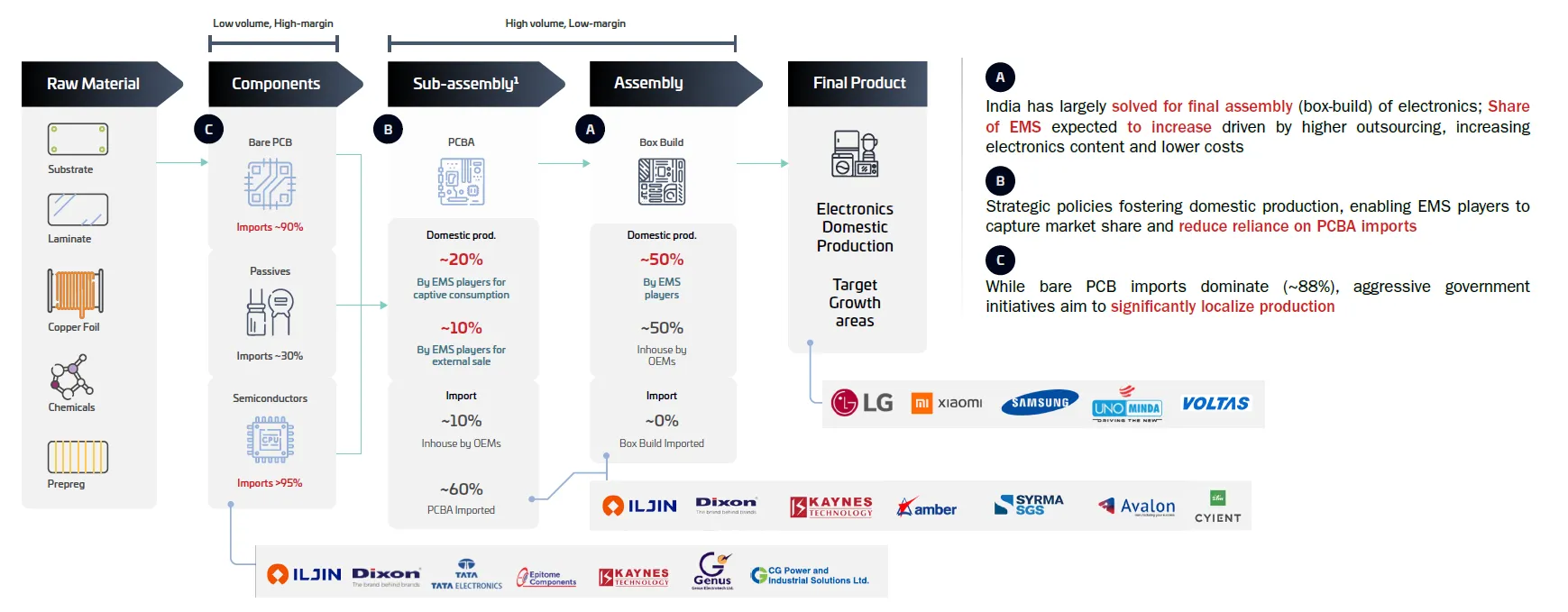

One reason is that a large part of the visible export boom is concentrated in final assembly, where value capture is limited. Domestic value addition in electronics at roughly 15–20%, with the government hoping to double it over time; it also points out China’s value addition is materially higher. This gap is the cleanest way to understand the plateau: India may ship a lot of electronics, but it keeps importing much of the depth that determines profit pools, resilience, and bargaining power.

India had an electronics trade deficit of US$54 billion in FY24, an indicator of both scale and dependency. EMS players contribute ~25% to domestic electronics production, below the ~35% global average, implying “headroom” but also showing India is still behind on outsourcing depth and ecosystem maturity. When EMS grows inside a shallow component ecosystem, growth becomes fragile: the factories scale, but the supply chain leverage doesn’t.

If the goal is to build an electronics base that is not just large but strategically durable, “more assembly” is not enough. The real question is whether India’s EMS layer can escape the low-margin middle and move toward higher value capture either through scale that creates bargaining power, or through capability that creates switching costs. Right now, most firms are stuck between those two outcomes.

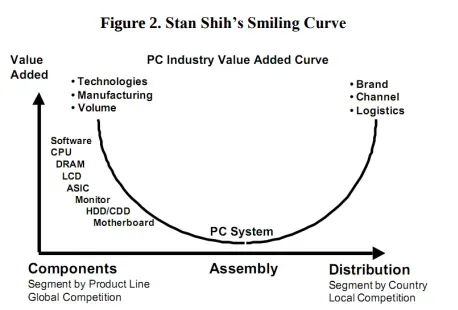

EMS is structurally disadvantaged because it sits between the owners of IP (brands/OEMs) and the makers of critical components. This is the “Smile Curve” dynamic: the ends of the chain (IP and key components) capture more value, while the middle (assembly/EMS) captures less. The result is a business that can grow huge in revenue yet remain thin in profit.

In most electronics products, components account for around 70% of total cost, with the EMS firm often buying parts and passing them through near cost; the money is made on the remaining portion - assembly, testing, logistics, execution. The brand owns the demand, the design, and the roadmap. The EMS firm mostly owns execution.

This is why the industry’s default margin profile is so unforgiving. In a world where 2% is normal, tiny shocks from yield issues, demand correction, delayed component shipments, warranty spikes etc. can all erase profits for a year.

The trap deepens because much of the EMS work is replicable. If one firm can reliably assemble phones, another can learn to do the same without needing to invent the underlying technology. That keeps competitive intensity high and pricing discipline low. The business becomes a race to scale and efficiency rather than a race to differentiated value.

The same 2% margin on ₹50,000 crore of revenue is a very different business than 2% on ₹20,000 crore, because fixed costs get absorbed, procurement improves, and working capital bargaining power rises. Scale also changes supplier negotiations: buying larger volumes across multiple customers can deliver better prices on commodity parts and sometimes allows partial backward integration.

But the scale is unevenly distributed. In India’s current landscape, a small set of firms sit closest to global OEM demand, and the rest compete for fragmented programs. When the best programs concentrate among a few, the industry becomes barbell-shaped: a handful of scaled winners and many mid-sized firms with insufficient leverage. When demand is strong and subsidies flow, even mid-tier players look strong. When demand slows or incentives fade, the economics revert quickly to the harsh baseline.

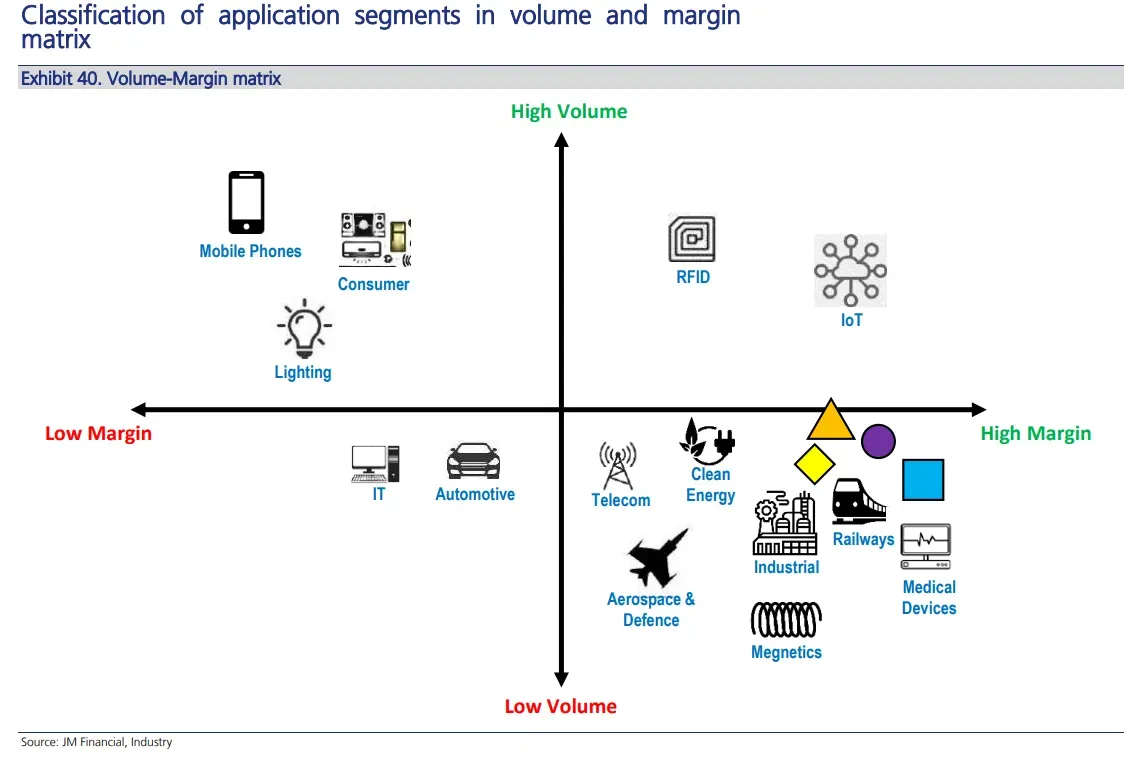

The alternative to pure scale is to move toward low-volume, high-mix manufacturing such as automotive electronics, medical devices, defence, industrial systems where lifecycles are longer, certification is heavier, and switching suppliers is slower.

But this path has its own friction in India. High-mix sectors require deep process control, compliance infrastructure, documentation culture, specialised testing, and a supplier base that can meet tighter tolerances consistently. Those capabilities take years to build and are easier when you already have a dense component ecosystem nearby. India is still in the “building the base” phase, which makes the leap into high-mix a long, cash-intensive climb.

So the industry is stuck between two difficult options. Scale requires winning huge programs and building cash-cycle leverage. High-mix requires building capability and ecosystem depth. Many firms have neither fully, and the middle becomes a squeeze.

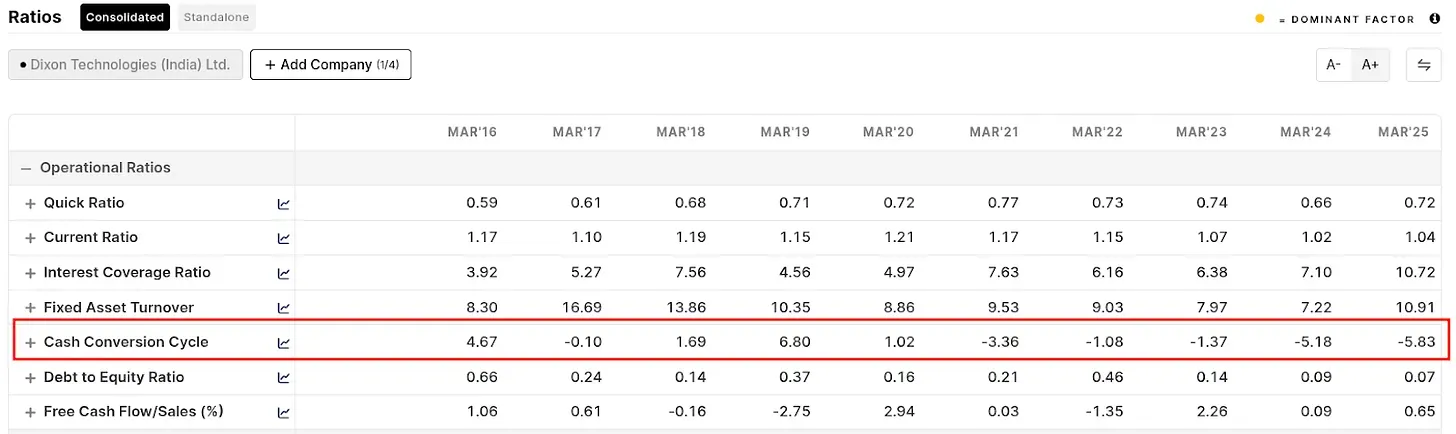

Margins get headlines, but working capital decides survival. The EMS model forces firms to finance the supply chain on behalf of powerful customers, and it punishes anyone without negotiating strength or cheap capital.

Suppliers often need to be paid within 30–60 days; production takes time; and large OEMs may pay 60–90 days after receiving goods. In plain terms, cash goes out faster than cash comes in. The longer and larger you run, the more cash you must trap inside inventory and receivables unless you can bend terms in your favour.

This is why the same margin can produce radically different outcomes across two EMS firms. A company with better payable terms, tighter inventory planning, and faster customer collections can run a lighter cash burden. A company without that leverage ends up borrowing to fund routine operations. EMS players routinely take loans to meet payments because so much cash is trapped in the cycle.

The working-capital problem is amplified in India because the cost of capital is meaningfully higher than in many competing manufacturing bases. Even if the operational model is similar, financing the same cycle costs more. In a 2–4% net margin business, a few percentage points of extra financing cost can consume a large portion of profit.

The structure of contracts matters. In a consignment model, the OEM owns the components and the EMS firm earns a conversion fee. In a turnkey model, the EMS firm sources components, manages suppliers, and assembles the product, taking both inventory risk and supplier risk. Turnkey can look like “more value-add,” but it is also more cash-intensive and more fragile when demand swings.

Most Indian EMS players are turnkey-heavy, which creates risks: if turnkey part prices spike, it’s the EMS firm’s problem; if a critical part is delayed, production stops; if demand drops, the firm is stuck with inventory and capacity it already paid for. This dynamic is a quiet reason Indian EMS can look great during upcycles and suddenly look stressed during downcycles.

The real moat in this world is not a single contract; it’s the ability to run the cash cycle better than peers. Dixon’s negative working capital cycle, getting paid before paying suppliers, as an example of how working capital can become a competitive advantage. But “negative cycle” outcomes are rare; most firms cannot achieve them because they lack the scale and customer mix needed to dictate terms.

So even as factories expand, the industry remains fragile. The treadmill is simple: more volume means more cash tied up, unless your bargaining power rises faster than your revenue.

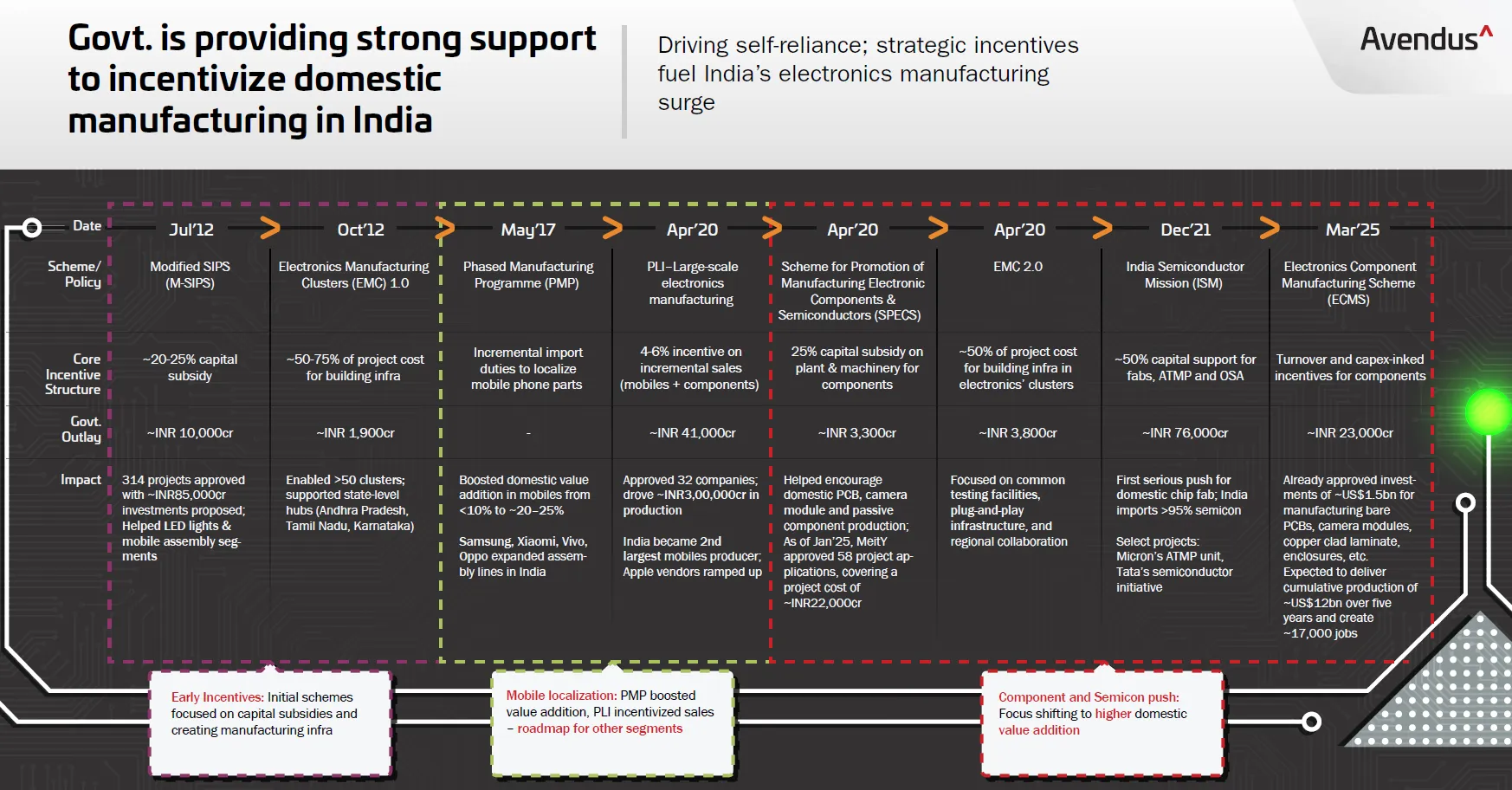

PLI was a catalytic policy success in one key sense. It proved India could attract and ramp large-scale electronics manufacturing quickly. Under the large-scale electronics manufacturing PLI, incentives of 4–6% on net incremental sales created a meaningful profitability layer on top of thin EMS margins. For a business earning 2–3% net margin, adding 4–6% changes the entire economic character.

But PLI also helped create the illusion that the “middle” problem was solved. Subsidies can offset structural disadvantages - logistics cost, thinner component ecosystems, higher working capital cost, but they don’t automatically remove them. And because PLI is time-bound, the underlying disadvantages re-emerge as soon as incentives fade.

Mobile manufacturing incentives expire in FY26, and as subsidies fade, “the original structural disadvantages don’t disappear.” That’s the heart of why the industry is stuck today. It used a window of policy tailwinds to grow volume, but the deeper ecosystem changes needed to protect margins and cash cycles are still incomplete.

Close to $1 billion (₹8,700 crore) was disbursed to 19 firms across 2022–23 to 2024–25, and that Foxconn, Tata Electronics, and Pegatron - all of which are Apple’s contract manufacturers received cumulatively over 75% of the amount. 5 beneficiaries collectively received more than 98% of total disbursals.

When the biggest incentives and the most scalable programs cluster around a few firms, the gap between “scaled winners” and “everyone else” widens. The mid-tier then faces a double squeeze: it competes for smaller, less sticky programs while trying to fund expansion in a high-cost-of-capital environment.

A concentrated incentive regime can still be rational, governments often back likely winners to build scale quickly. But it creates a policy-induced barbell. A barbell industry tends to feel “stuck” in the middle because the middle becomes a zone of permanent disadvantage.

If PLI was meant to buy time for ecosystem building, the key question becomes: what changed underneath during the window? Some things clearly improved: assembly scaled, exports grew, employment rose. But the persistent constraint is component dependency and low domestic value addition.

The gap between progress in final assembly and the next phase of growth, which it frames as sub-assemblies and core components where import substitution is “structurally larger and more strategic.” If that substitution doesn’t happen fast enough, EMS firms remain price-takers who import depth and export finished goods with limited value capture.

That’s why the industry feels stuck right now. The policy escalator is moving from “assembly” to “components,” but the transition is difficult, slow, and capital-intensive and the easy profitability boost from PLI is not permanent.

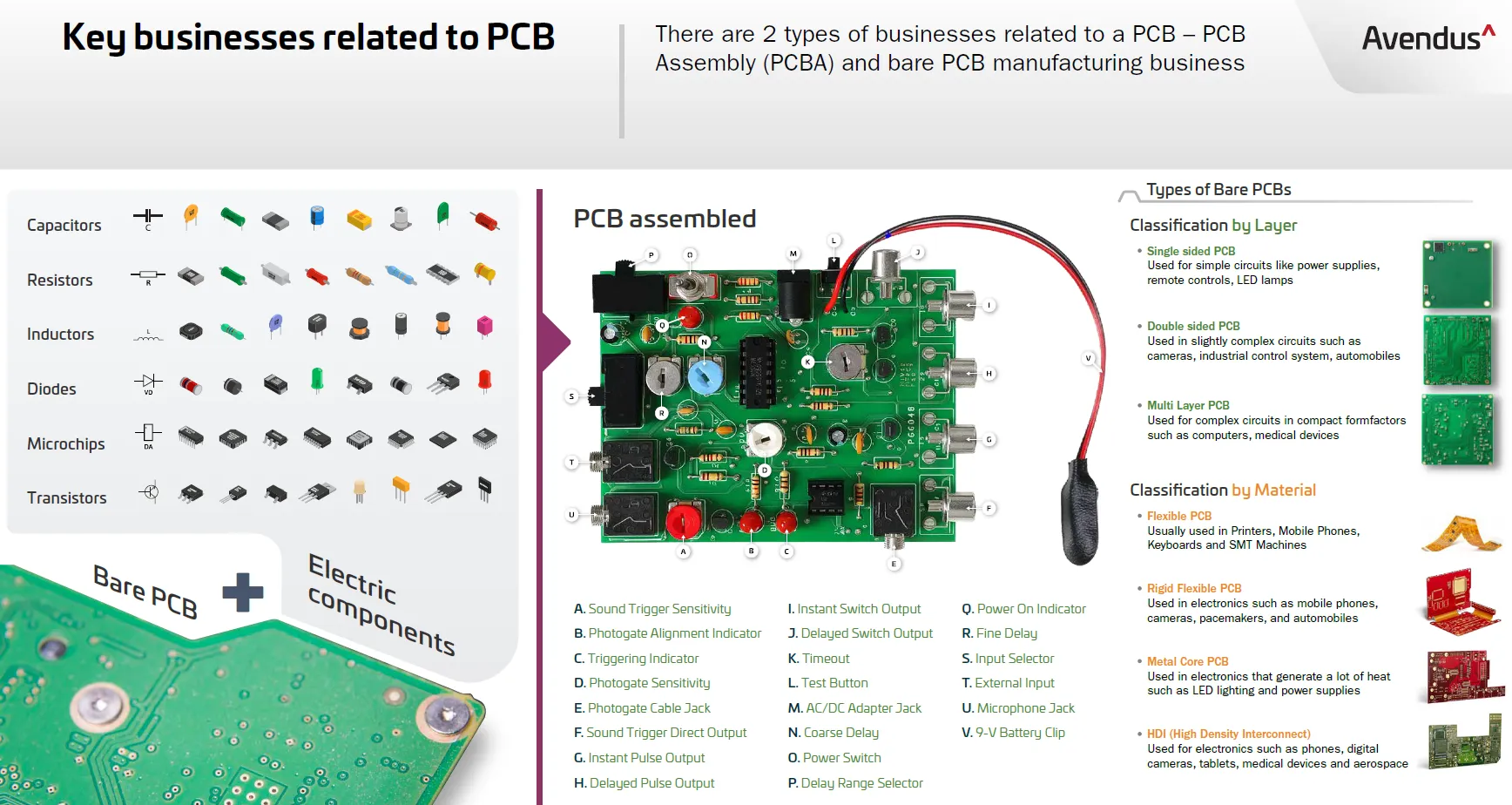

To understand why Indian EMS can’t escape the middle, look at components. India can assemble, but it still imports too much of what makes assembly valuable.

Electronics trade deficit at US$54 billion in FY24 - “the scale of the problem and the magnitude of the opportunity.” This deficit reflects the component content embedded across devices, IT hardware, industrial electronics, and telecom gear.

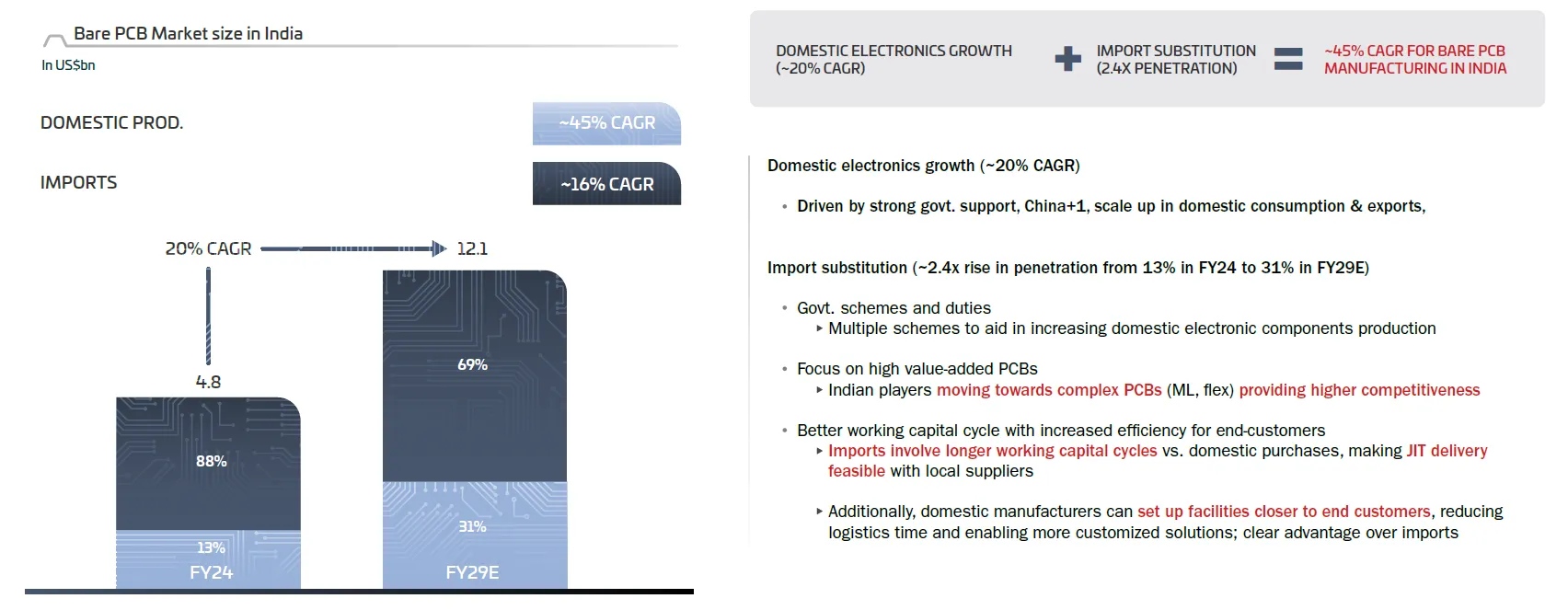

Even within a single component category bare printed circuit boards, the dependence is stark. India’s bare PCB market at ~US$5 billion with ~88% import dependence. That number explains why EMS margins remain constrained: if the backbone component is imported, you lose lead-time control, you lose working-capital efficiency, and you lose a chunk of value-add that could have sat domestically.

PCBs determine reliability, miniaturisation, and manufacturability. They also shape the economics of delivery. Imports involve longer working capital cycles than domestic purchases, while local suppliers can support just-in-time delivery and proximity advantages. This links component localisation directly to EMS cash cycles.

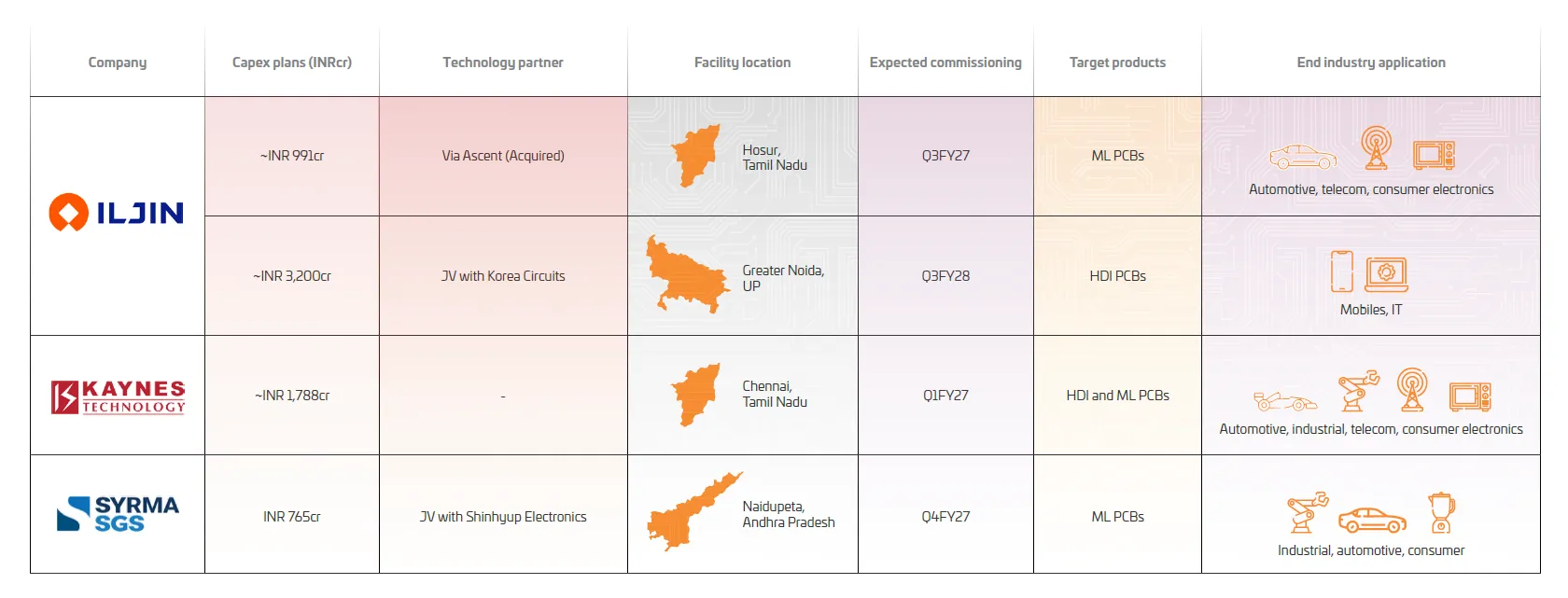

The forward projections show how large the shift could be if India executes. Domestic bare PCB manufacturing is expected to grow at ~45% CAGR over five years, reaching around US$4 billion by FY29E, alongside a ~2.4x increase in local sourcing penetration (from 13% in FY24 to 31% in FY29E). These are not small changes; they would meaningfully alter the bargaining power and operating rhythm of factories.

The Indian government is clearly trying to push the ecosystem down the value chain. The ECMS (Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme) is designed explicitly to deepen component and sub-assembly production. ECMS has a fiscal outlay of ~US$2.6 billion. PIB’s release on the second tranche reports 17 approved proposals under ECMS with ₹7,172 crore investment, projected production of ₹65,111 crore, and 11,808 direct jobs.

Indian EMS will not escape the middle by doing more of the same. The path out is a change in what factories mean inside the value chain.

If India reduces import dependence in high-impact components. EMS firms gain lead-time control, better working-capital cycles, and more leverage in negotiations.

The second unlock is engineering ownership. This is how EMS firms move from being priced on conversion cost to being paid for risk reduction.

The mismatch between supplier payment terms and OEM payment terms is a structural feature of the industry. India’s cost of capital makes this mismatch more painful. So “unstuck” also means building financing and supply-chain instruments that reduce cash stress for mid-tier firms; otherwise only the largest players will survive the next phase, and the ecosystem will remain barbelled.

Finally, India must accept what the “success” metrics should be. Export growth is important, but the more meaningful metric is domestic value addition rising materially above today’s ~15–20% range. If value addition rises, margins improve, component ecosystems deepen, and engineering talent compacts into clusters.

India’s electronics story is real but the next chapter is harder than the first. The next chapter is about proving India can own depth: components, engineering, quality systems, and supply-chain power. Until that depth arrives, Indian EMS will keep feeling stuck bigger every year, but still trapped in the middle of the smile curve.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart