by Siddharth Singh Bhaisora

Published On Feb. 20, 2026

For a country that wants to industrialise faster, create mass employment, and keep growth durable, private capital expenditure (capex) is supposed to do the heavy lifting. When businesses invest in factories, logistics, machinery, technology, and new capacity, they set off a chain reaction: suppliers get orders, jobs get created, productivity rises, and household incomes support the next wave of demand. That’s the virtuous cycle most high-growth economies ride.

India’s puzzle is that the economy has often looked strong on headline growth, and yet private capex has repeatedly failed to break into a sustained boom. Over the last 10 years+, private investment has steadily lost share, both in the economy and within total investment while the public sector has taken a bigger role. The result is what many now describe as a “private capex crisis”: not a collapse to zero, but a stubborn refusal to accelerate in the way India’s ambitions require.

And yet, the same data that diagnoses the malaise also hints at something else. The pace of weakness may be moderating, the composition of investment is slowly improving, and conditions for a turn are quietly building. The private capex story may be closer to bottoming out than it appears.

Private capex is the money businesses spend on long-term productive assets such as factories, plants, machinery, logistics capacity, R&D facilities, and other investments that expand the economy’s ability to produce and employ.

Unlike consumption, it builds future supply. Unlike government capex, it is usually tied directly to commercial demand and tends to create self-reinforcing cycles of jobs, income, and repeated investment.

A growth model dominated by public infrastructure can lift demand for cement, steel, and construction services, but it may not be as durable as a model where companies continuously build capacity because they foresee stable, profitable demand.

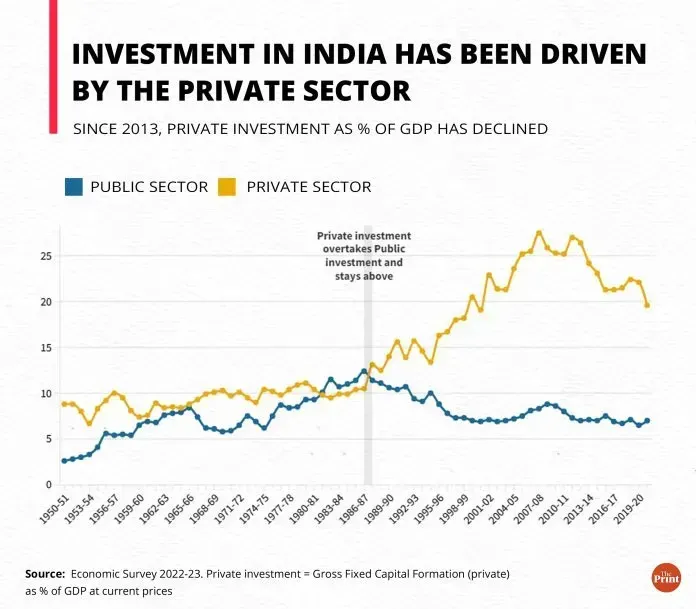

To understand today’s caution, it helps to start with where India came from. Private investment as a share of GDP peaked around 27% in 2007–08, recovered to about 27% again by 2011–12, and then entered a long decline, sliding to roughly 21% by 2015–16 and largely hovering around that level since.

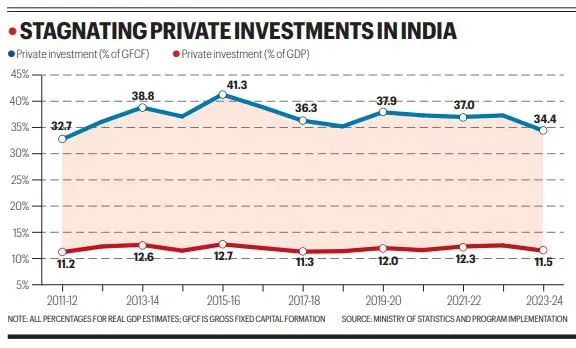

The private sector’s share of total fixed investment has shrunk from over 40% in 2015–16 to about 33% in 2023–24, implying that even when the overall investment pie grows, the private slice has not kept pace.

Another way to see the same dynamic is through the national accounts lens. Private capex has been stuck at around ~12% of GDP for more than a decade, while its share of total investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, or GFCF) fell to 34.4% in 2023–24, one of the lowest readings in more than a decade. This has happened even though GFCF overall has recovered from the mid-2010s lows. Total investment as a share of GDP rose from under 31% in 2016–17 to 33.7% in 2024–25, yet still below the mid-2010s/early-2010s highs.

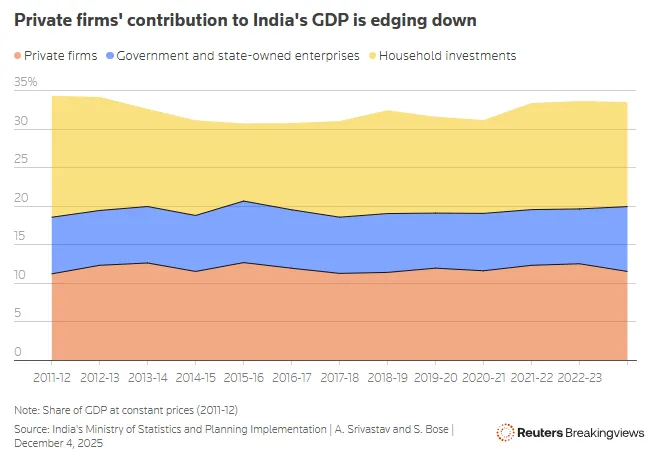

The picture that emerges is not of an economy starving for investment altogether, but of an economy where public capex and household investment have increasingly dominated the cycle while corporate India stays selective and cautious.

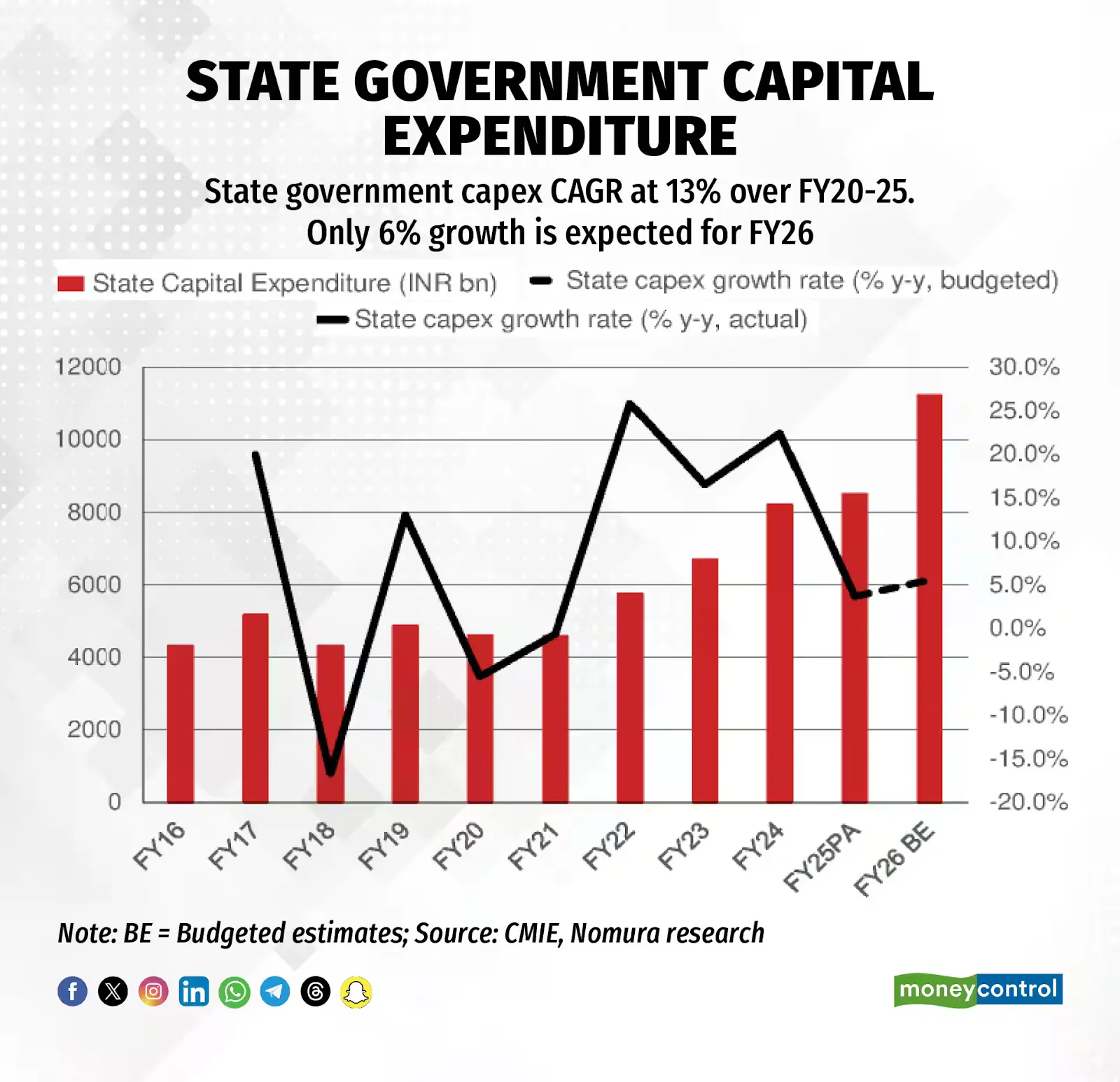

One reason India has been able to maintain solid growth despite private hesitation is that the public sector has stepped into the breach. Public investment directly through government capex and indirectly through state-owned enterprises has risen to unusually high levels by historical standards, with public spending (including state-linked entities) reaching about 8.4% of GDP in 2023–24, described as a multi-year high.

The most recent budget signals that this strategy is continuing. The government’s revised estimate (RE) of capital expenditure for 2025–26 is about ₹11 lakh crore, and the fiscal deficit target for 2026–27 is 4.3% of GDP, indicating an attempt to balance investment support with fiscal consolidation. Independent budget analysis summaries also note a planned increase in public capex from about ₹11.2 lakh crore to ₹12.2 lakh crore (budget estimate), reinforcing the intent to keep infrastructure momentum going.

This public push has real benefits: roads, rail, ports, power networks, digital infrastructure, and urban projects reduce logistics costs, raise productivity, and create the “platform” private industry needs. But governments can’t be the only engine forever. Unlike businesses, they face harder budget constraints over time, and they must allocate resources across competing priorities (health, education, social protection, defence). Even a well-executed public capex wave is ultimately meant to crowd in private investment, not replace it.

Many large firms today have stronger balance sheets than they did a decade ago. The core issue is closer to: will the demand be there, and will it be durable enough to justify long-gestation projects?

A useful proxy is capacity utilisation. Many firms expand only when existing plants are running hot and order books are strong. But surveys and reporting around industrial utilisation show India hovering in the mid-70s which isn’t weak, but not boom-level either. For example, manufacturing capacity utilisation was reported at 74.3% (up marginally from 74.1%) in mid-2025 readings, a level that often sits below the trigger point for aggressive private capacity expansion.

The “mid-70s trap” matters because it keeps boardrooms in wait-and-watch mode. If utilisation is stable but not tightening, companies can meet incremental demand by sweating existing assets, improving efficiency, outsourcing, or debottlenecking—strategies that require smaller capex than building entirely new capacity.

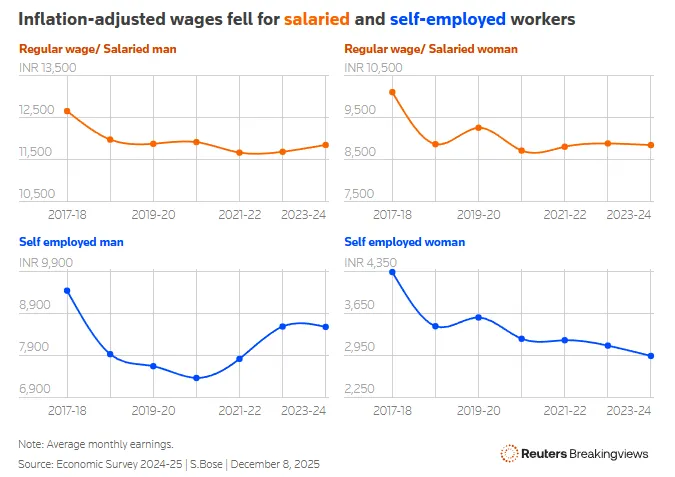

Meanwhile, domestic demand has had a mixed character: pockets of premium consumption look strong, but broad-based purchasing power and wage momentum have not always convinced firms that the next decade will deliver the kind of volume growth that justifies big bets. Global conditions add another layer of uncertainty: export demand cycles, trade friction, and geopolitical risk can make long-horizon projections feel fragile.

India’s last major private capex surge (mid-2000s to early-2010s) ended painfully for many firms. Over-optimistic demand assumptions, project delays, regulatory friction, and the subsequent stress in infrastructure and power created a corporate and banking clean-up that dominated much of the 2010s.

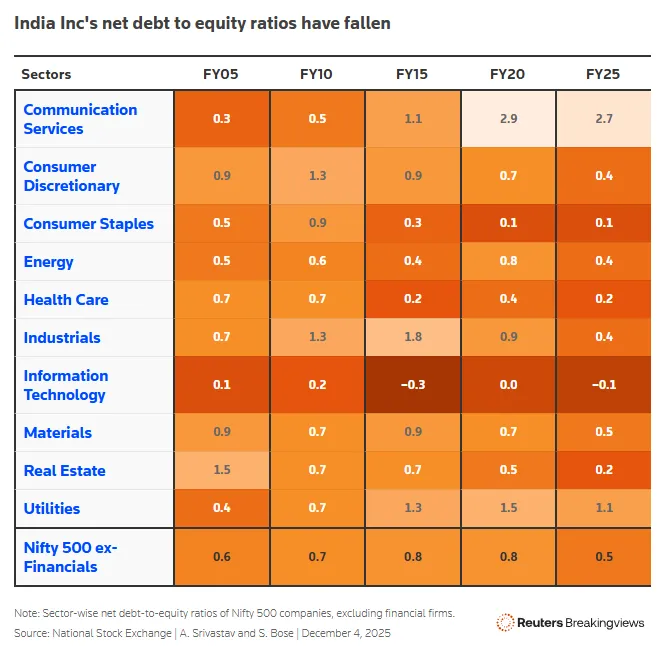

That experience has changed corporate risk culture. Even now, many large business groups prefer to keep leverage conservative. Data cited in commentary has pointed to net debt around 1.9× EBITDA for large firms and highlighted that, despite healthier balance sheets, the preference is to avoid a repeat of overreach. This caution is rational at the individual-firm level, but it becomes a macro problem when everyone waits for perfect clarity before investing.

One macro symptom of this is a higher incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR), a sign that each unit of growth is requiring more capital, often because investment is skewed toward public infrastructure and because productivity gains from private-sector scale are not fully kicking in. Estimates have put India’s ICOR around 4.4, higher than the ~3.8 seen during earlier boom years. (ICOR isn’t destiny, but it’s a useful indicator that the growth model may be becoming more capital-intensive without a commensurate private productivity dividend.)

One reason the private capex debate gets confusing is that different datasets tell different stories.

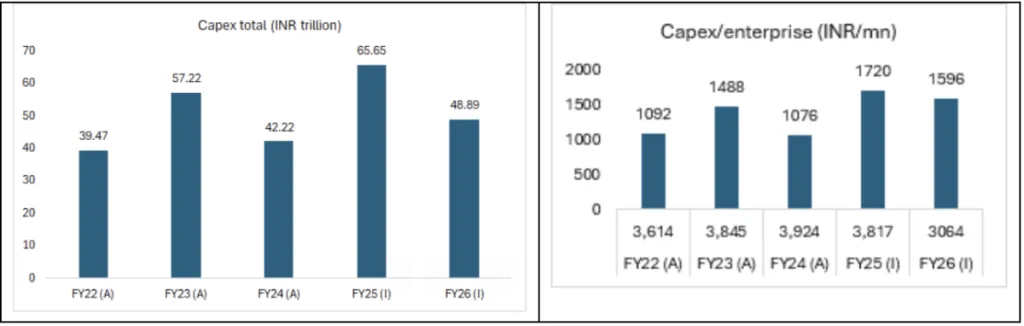

On one hand, measures based on listed companies show real activity. For instance, capex of nearly 2,000 listed non-financial companies was estimated to rise 11% in 2024–25 to ₹9.4 trillion (after adjustments), and corporate balance sheets for a broader set of firms showed gross fixed assets up 8.5% year-on-year as of end-September 2025.

On the other hand, the national accounts and broader economy-wide measures still show private capex stuck near 12% of GDP and private share of overall investment at subdued levels. The reconciliation is that India does see meaningful private investment, but it is uneven across sectors and firm sizes, and it doesn’t yet add up to a widespread, self-sustaining capex cycle.

A forward-looking survey of private corporate capex intentions projected a sharp year-on-year drop in intended private capex for FY26 to ₹4.88 trillion, from ₹6.56 trillion in FY25, roughly a 25–26% decline. The same material notes that the survey covered large enterprises and that response rates and coverage caveats matter when interpreting the results (for example, a sizable share of surveyed firms did not report intentions).

At the same time, other survey outputs around actual and near-term capex behaviour paint a more nuanced picture. Official releases on private corporate sector capex trends note that provisional capex per enterprise for acquiring new assets in 2024–25 was about ₹172.2 crore, with ~53.1% of capex used for machinery and equipment and meaningful shares going to work-in-progress and buildings/structures. They also suggest many firms are investing for income generation and upgradation, and that a substantial portion plan capex on core assets.

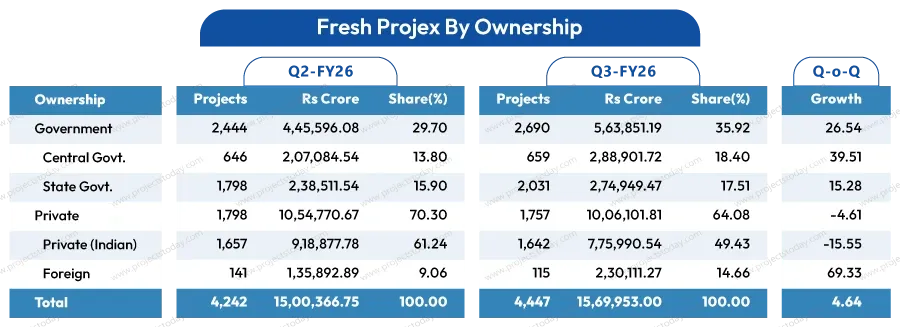

Fresh private-sector investment intentions were reported to decline for the second consecutive quarter, but with a crucial twist: the pace of decline moderated.

In one recent quarter’s tracking:

Fresh private investment intentions fell 4.61% quarter-on-quarter to about ₹10.06 lakh crore.

Within that, domestic private (Indian) companies’ commitments dropped much more sharply by 15.55% to about ₹7.76 lakh crore, while foreign-linked commitments rose (helped by a few mega projects).

The public sector share of new proposals rose, reflecting larger ticket sizes and continued infrastructure push.

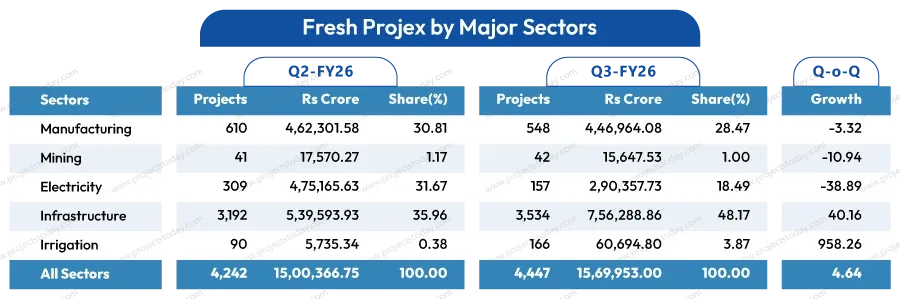

The sectoral composition is revealing. Manufacturing, often the bellwether for private appetite, showed a modest decline in announced value (about -3.32%) and a sharper fall in the number of new projects (about -10.16%) in that quarter, with heavy industries like steel, cement, and autos dragging. Yet even within manufacturing, some newer growth areas (such as electronics, pharma, and defence-linked manufacturing) were described as improving. Meanwhile, big-ticket announcements appeared in new-economy infrastructure like data centres and in energy storage, underscoring that the capex that is happening is increasingly tilted toward the future.

This is important for the “bottoming out” question: when a decline continues but becomes less steep, and when the mix shifts toward emerging sectors it often signals that a cycle is transitioning from contraction to consolidation.

Over the years, policymakers have tried multiple levers: cleaning up bank balance sheets after the NPA cycle, recapitalising lenders, lowering corporate tax burdens, rolling out production-linked incentives, and expanding public capex to crowd in the private sector. Yet the private response has been slower than hoped.

This doesn’t mean the interventions were useless, many of them improved the economy’s plumbing. It means the binding constraint may not be liquidity or headline profitability alone. The binding constraint is often a blend of:

Demand confidence (will utilisation tighten sustainably?),

Execution confidence (will projects be completed on time with predictable rules?),

Competitive clarity (can Indian producers scale without being undercut in cyclical downturns?), and

Global visibility (are trade and supply chains stable enough to bet big?).

But several indicators suggest the private capex cycle may be closer to a turning point than the headline narrative implies. Two consecutive quarters of decline is not good news, but the fact that the pace is moderating..”

Even as traditional big spenders (steel/cement/autos) appear cautious in announcement data, the rise of large projects in AI/data infrastructure, energy storage, electronics, and select manufacturing sub-sectors suggests capex is not disappearing, it’s rotating. The continued push toward ₹11–12 lakh crore-plus public capex levels, alongside efforts to improve the “investability” of infrastructure projects, can reduce risk premia for private participants over time.

As inflation cools and rate-cut expectations build, the cost of capital becomes less of a deterrent, especially for long-gestation projects. Reporting around easing cycles and demand softness has strengthened the case for monetary support.

The most constructive way to read the current “private capex crisis” is not as permanent decline, but as a prolonged transition, from a debt-fuelled, infrastructure-heavy boom of the past to a more diversified, technology- and productivity-led investment cycle.

Three forces make that transition plausible:

Roads, logistics, power reliability, and digital infrastructure funded by public capex lower the hurdle rate for private projects over time.

New sectors such as data centres, electronics supply chains, energy transition infrastructure, are naturally capex-intensive and often scale faster once they start.

When declines moderate and investment shifts toward “future” categories, it often marks the late innings of a downcycle.

So yes, India’s private capex has been falling as a share of the economy for years, and the latest indicators still show caution. If the next few quarters bring (a) steadier utilisation gains, (b) continued policy focus on execution certainty, and (c) a stable external environment, the private sector just needs enough confidence to move from postponing big decisions to progressively approving them.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart