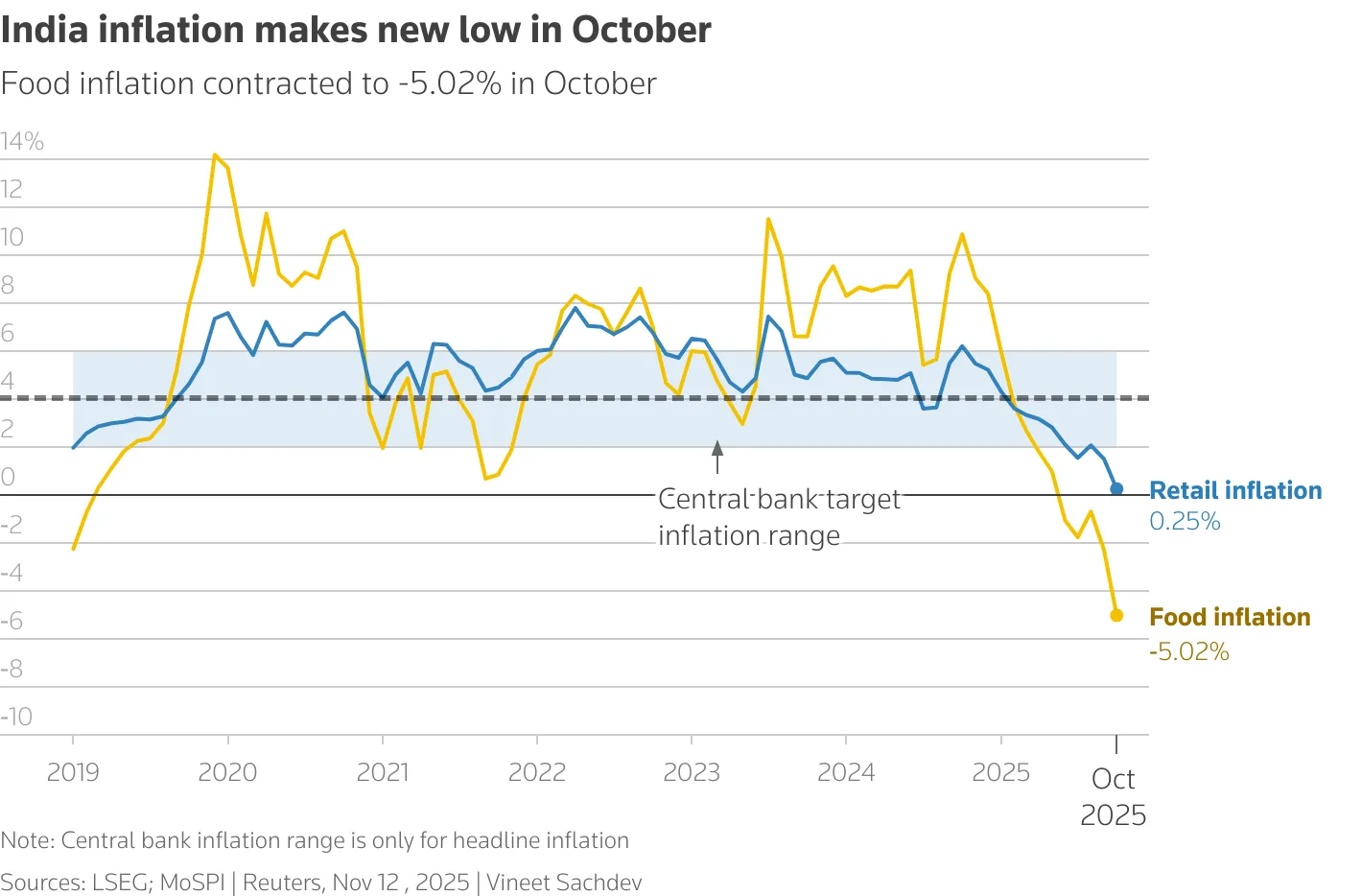

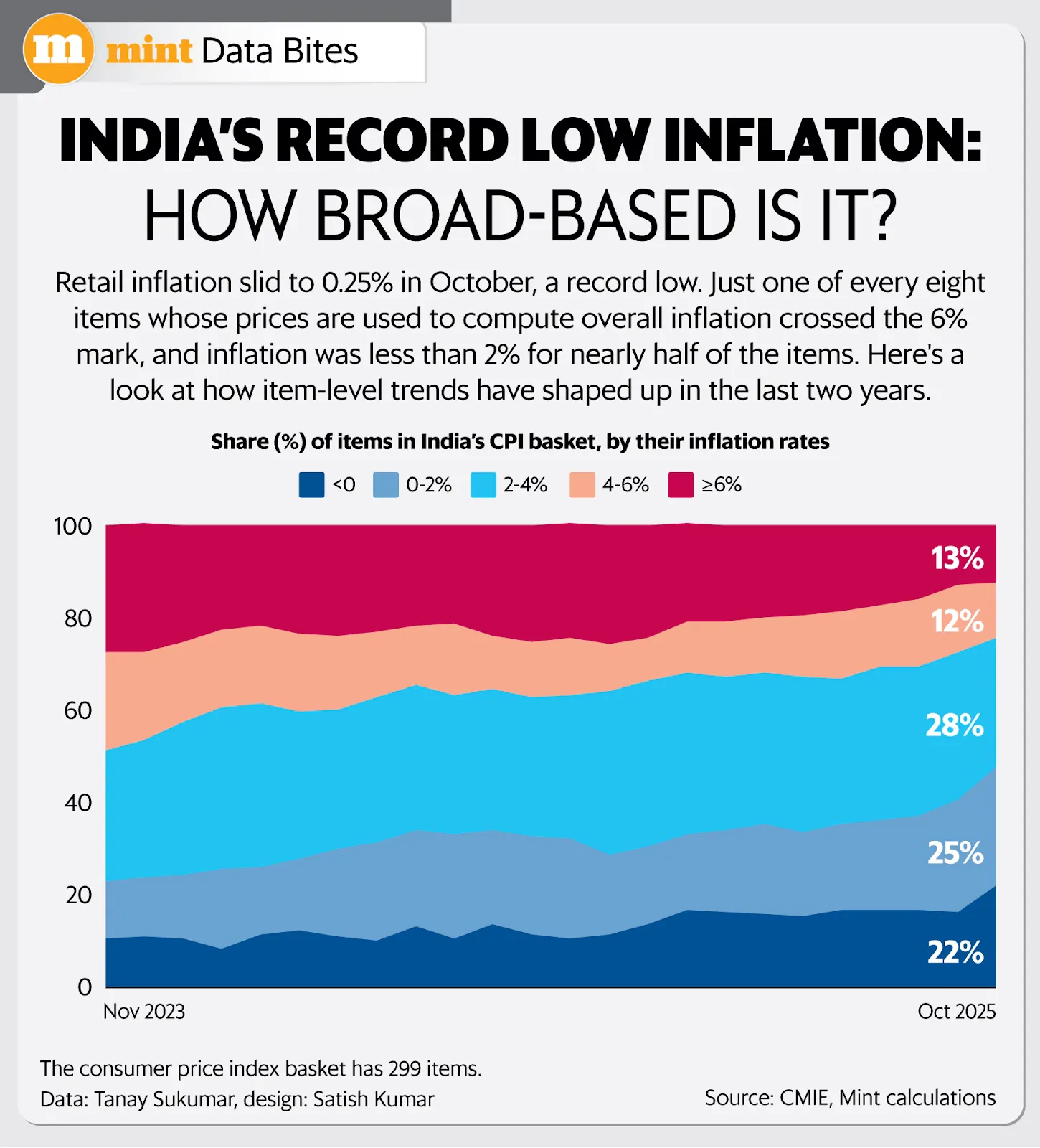

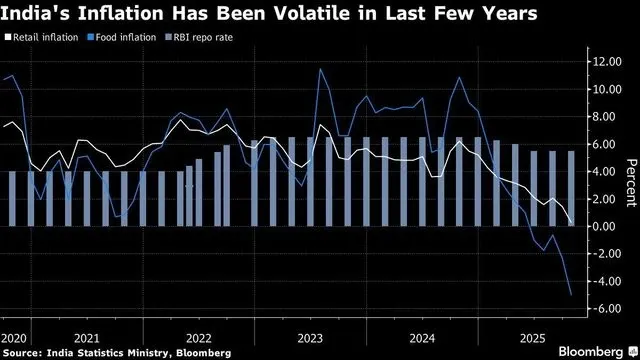

India is living through an inflation moment that would have sounded implausible a few years ago. Retail inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) crashed to just 0.25% in October 2025, the lowest print since the current CPI series began in 2013. This comes barely a year after inflation was above 6%, breaching the RBI’s tolerance band of 2–6%.

This sharp disinflation is not happening in a weak economy. Real GDP growth in the April–June quarter was around 7.8%, and full-year growth is projected in the high-6% range which is strong by global standards. That combination of very low inflation and robust growth is what makes India’s current macro backdrop so unusual. It gives policymakers space to cut interest rates, but also raises questions about whether such a move is necessary or even wise.

To understand India's near zero inflation and its policy implications, it helps to unpack the drivers: food prices, tax policy, statistical base effects, household expectations and the RBI’s own track record on monetary transmission.

Watch the full video here:

On the one hand, the data are strikingly benign. CPI inflation is near zero; wholesale prices (WPI) are also in negative territory, with a 1.2% year-on-year fall in October. On current projections, headline inflation could average around 2.5% in FY26, and CPI excluding gold is expected to remain negative for a couple of months.

On the other hand, this unusually low inflation is occurring in a world of substantial external risks. Global growth is patchy, and India is dealing with steep US tariffs of around 50% on several exports, which pose challenges for MSMEs and labour-intensive sectors. The RBI’s monetary decisions now have to be made with both domestic disinflation and external vulnerability in mind.

Domestically, the low inflation print comes after 9 consecutive months of CPI staying below 4%, the target midpoint of the RBI’s 4% ± 2% band. This suggests that the disinflation is not just a single freak reading, but part of a broader trend, albeit one with heavy food and tax components.

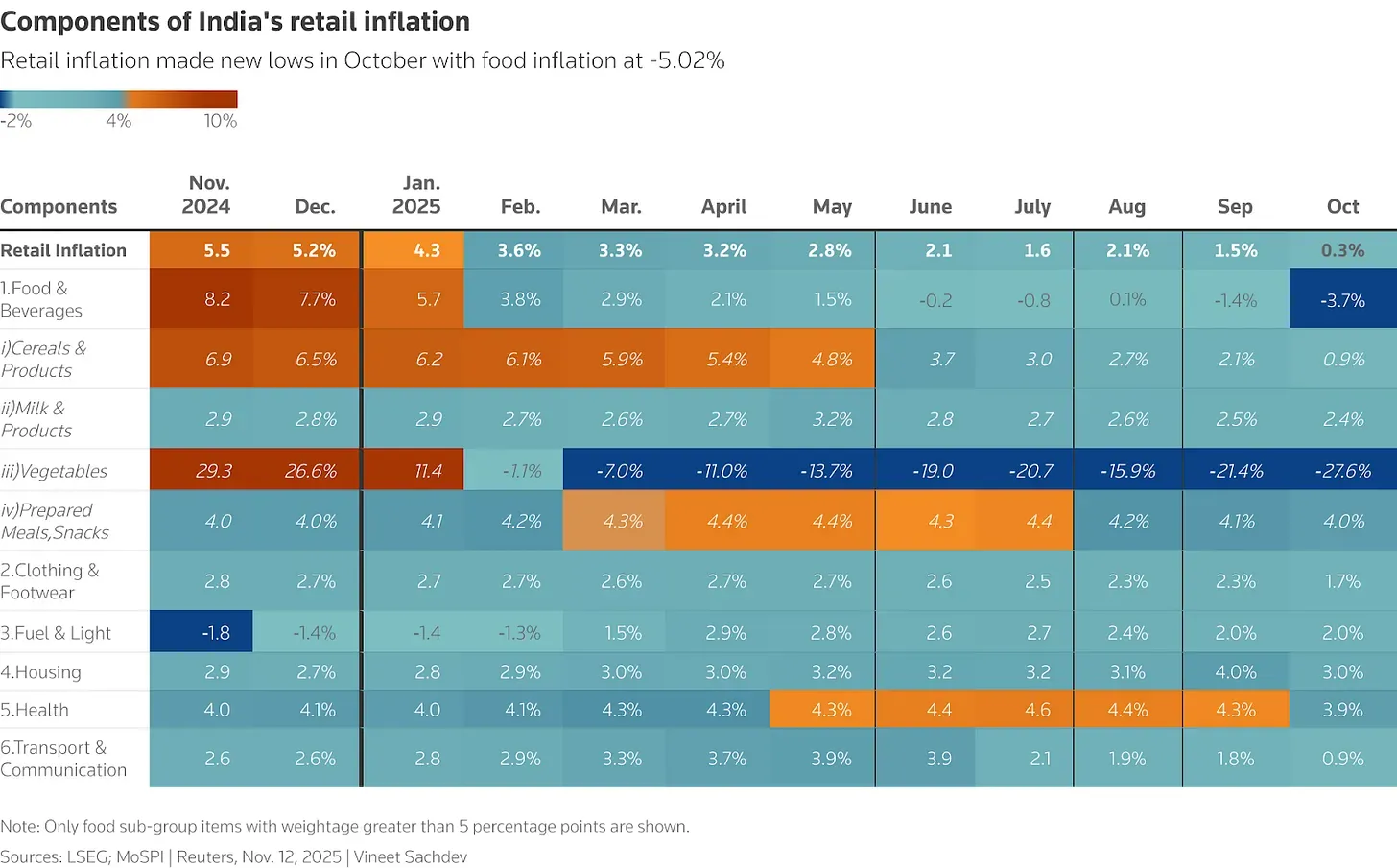

The single biggest contributor to October’s collapse in inflation is food. “Food and beverages” — which account for almost half of the CPI basket — have moved from high inflation last year to deep deflation this year. Vegetables that were over 30% more expensive a year ago are now more than 25% cheaper on a year-on-year basis, while pulses have also seen double-digit price declines.

This flip in food prices reflects a mix of good luck and policy. On the luck side, India has enjoyed exceptionally good monsoon rains and a bumper kharif harvest, which translated into large supplies of vegetables and pulses. On the policy side, the government leaned heavily on supply-side tools — allowing duty-free or low-duty imports of pulses and edible oils, and releasing onion stocks from buffer inventories ahead of the festive season. Together, these factors reversed last year’s food-price spike and dragged the overall CPI down.

The impact is uneven. For urban and rural consumers, lower food prices are an immediate relief. But for farmers and other rural producers, collapsing prices mean squeezed incomes. The same forces that are celebrated as “disinflation” in macro statistics can feel like a price crash at the mandi gate.

A second driver is tax policy. The September 2025 GST rationalisation compressed slabs and moved several mass-consumption items into lower tax brackets. As those cuts filtered through into retail prices, they knocked down inflation in clothing, footwear, household goods, and various consumer durables.

Core inflation, which strips out food and fuel, superficially looks higher than the headline number, at about 4.3–4.4%. But that figure is distorted by one outlier: gold. The precious metal sits inside the “personal care and effects” bucket in CPI, and gold prices are nearly 58% higher than a year ago, pushing that sub-index up sharply. If you exclude gold, prices of most core goods are flat to mildly positive, while many services categories (housing, health, education) are rising in the low-single digits — “sticky but not scary.”

In other words, this is not a classic demand-crash story where everything in the economy goes into deflation. It is a highly skewed disinflation, dominated by a short, sharp correction in food and a one-off tax change.

A third piece of the puzzle is purely statistical. In October 2024, inflation was above 6%, marking one of the highest readings in recent years. When you compare today’s price level to that inflated base, the year-on-year change looks unusually low. That “base effect” amplifies the impact of falling food prices and GST cuts, making inflation appear even more subdued.

This matters for interpretation. The low year-on-year print does not automatically mean that the monthly pace of price increases has collapsed in a lasting way. Some of the story is genuine disinflation, and some is the arithmetic of starting from an unusually high base.

Here is the paradox: while official inflation has nearly hit zero, households feel that prices are much higher. The RBI’s latest household inflation expectations survey suggests that consumers think current inflation is around 7.4%, and expect it to climb towards 8.7% over the next year.

Such surveys almost always overshoot actual inflation, but the current gap is unusually large. One explanation is that older households that lived through the high-inflation 2000s and the post-COVID price spikes anchor their expectations to those experiences.

Another is salience bias: people remember big jumps in milk, rent or school fees more vividly than gradual declines in vegetables or edible oils. Media coverage also tends to highlight price spikes rather than slow, boring disinflation.

The result is a two-track reality. In the data, inflation has zeroed out. In people’s heads, it remains uncomfortably high.

And this expectation gap has very real consequences. With CPI inflation at 0.25% and the 10-year government bond yield around 6.5%, India is delivering one of the highest “real” interest rates in the world — close to 6 percentage points above inflation.

For investors in government bonds and other fixed-income assets, this is a dream: they are being paid handsomely in real terms. For borrowers, it is the opposite. The cost of capital remains punitive, especially compared with economies where inflation is still 3–4% and long-term yields are only slightly higher than India’s.

The RBI did try to ease earlier in 2025, cutting the repo rate by roughly 100 basis points between February and June. But those rate cuts barely fed through. Long-term bond yields fell only about 20–25 bps, and average lending rates on new loans dropped by less than a percentage point. The transmission problem where policy moves in Mumbai do not fully reflect borrowing costs across the economy, remains a structural constraint.

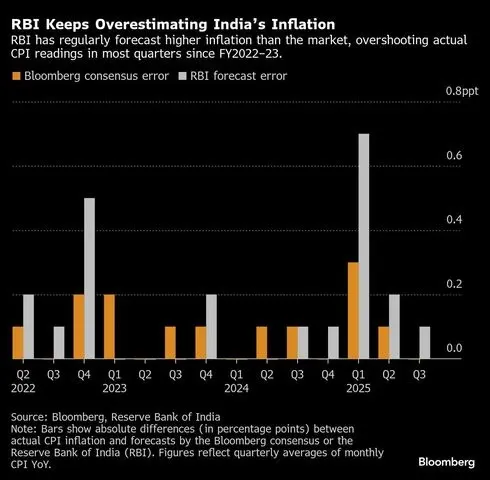

Reserve Bank of India’s inflation-forecasting model is under growing scrutiny because it has repeatedly overestimated price pressures through 2025, pushing policy into a more hawkish stance than the data ultimately justified. In the first three months of the year, the RBI’s inflation projections overshot actual outcomes by about 0.7 percentage points – its biggest miss in nearly six years – with smaller but still notable errors of 0.2 and 0.1 points in the next two quarters. Economists now expect another sizable miss after the surprisingly soft October inflation print, which has already rendered the RBI’s recent forecast of 2.6% inflation for the fiscal year through March outdated; private estimates cluster closer to 2.0–2.2%, near historic lows, versus the central bank’s 4% target.

These misses matter because they help explain why monetary policy has stayed tighter for longer. Relying on a model that kept flagging higher price pressures, the RBI has been cautious about cutting rates, even as actual inflation fell sharply. Economists argue that when forecasts are systematically biased on the upside, real interest rates end up unintentionally high, risking weaker growth and raising questions about the credibility of the framework. The main culprit has been food inflation: a favourable monsoon, strong harvests and better supply chains dragged food prices down much faster than the model anticipated, pulling headline inflation with them.

The RBI has already upgraded its forecasting framework to “QPM 2.0” and is tweaking it further, but some of the problem lies in data and structure, not just equations. The CPI basket itself is outdated and due for revision, and the RBI has also misread growth at times, over- and under-estimating GDP across quarters. The takeaway is that while models are essential for forward-looking policy, the central bank may need to lean more heavily on incoming data and shorter-horizon guidance, especially on volatile food prices, instead of putting too much weight on long-range point forecasts that keep missing on the same side.

India operates under a flexible inflation targeting regime, with a formal goal of 4% inflation and a tolerance band of 2–6%. With inflation below 4% for nine straight months and now even below 2%, the standard playbook would say the RBI has to loosen policy so inflation drifts back towards target from below.

From this perspective, a December rate cut looks not just defensible but desirable. Lower policy rates could reduce borrowing costs for households and firms, energise investment, and support consumption. Cheaper loans would particularly help homebuyers, car purchasers and consumers of durables, while still-benign inflation would protect real incomes.

Another argument for easing is to avoid what economists call “deflationary psychology”. If people come to expect ever-lower prices, they may delay purchases and capex, waiting for better deals. Over time, this can sap demand, slow growth and paradoxically make it even harder to push inflation back up — a dynamic seen in parts of Europe and Japan in earlier decades. Some Indian economists warn that persisting with very tight real rates when inflation is near zero risks nudging behaviour in that direction.

The other side of the debate points out that today’s low inflation is not fully “earned” by structural reforms or a deliberate policy strategy; it is heavily shaped by transitory factors: an exceptional harvest, aggressive food-supply management, GST tweaks and a base effect. As these fade, prices — especially food prices — could bounce back.

This camp notes that growth is currently strong, driven by public capex, tax-buoyed revenues and resilient urban consumption. With Q2 GDP likely above 7%, the economy does not appear starved of demand. Cutting rates into such strength might fuel asset-price froth more than productive investment, while creating confusion about the RBI’s reaction function.

External factors complicate things further. The US tariff shock raises uncertainty for exports; global growth is fragile; and any spike in global commodity or energy prices could transmit into Indian inflation fairly quickly. Against that backdrop, some analysts argue the RBI should treat the current disinflation as a valuable buffer rather than a prompt to immediately ease.

Finally, there is the issue of credibility and expectations. If households already expect 7–8% inflation, a premature or poorly explained rate cut could be misread as the RBI going soft on price stability, reinforcing those high expectations. Conversely, a well-telegraphed, moderate cut, with clear guidance about future moves and close monitoring of inflation data, could help re-anchor expectations around 4%.

Sustained inflation near zero with very high real rates can morph into a low-inflation trap. Businesses facing uncertain demand and high borrowing costs delay expansion. Households, especially at higher income levels, prefer financial savings over consumption. The economy can keep growing for a while, powered by government spending and select sectors, but private-sector risk-taking may stagnate.

If this coincides with weaker external demand or another policy shock, growth could slow sharply, and the RBI would then have to cut rates more aggressively in a less favourable environment. The current disinflation is therefore both a comfort and a warning: it gives space to act, but also signals that policy may already be tighter than necessary.

A second risk is distributional. Food deflation is a blessing for consumers but a curse for producers. If farm-gate prices remain depressed for too long, rural incomes will suffer. This can hurt demand for everything from two-wheelers and fertilizers to FMCG products, hitting corporate earnings and job creation.

At the same time, high real interest rates favour savers with financial assets — typically more urban and affluent households. The combination of rural price stress and high financial returns in cities could widen inequality. For a country that still relies heavily on rural consumption as a growth engine, that is a macro risk, not just a social one.

A third risk is that even if the RBI does cut rates, the transmission problem persists. The experience of early 2025 — 100 bps of repo cuts translating into only modest reductions in bond yields and lending rates — suggests that structural frictions in the banking system, elevated risk premiums and heavy government borrowing can all blunt the impact of easier policy.

If the central bank uses up precious conventional policy space but the real-economy impact is muted, it may find itself with less room to respond to future shocks. That reality argues not just for careful timing of rate cuts, but also for parallel efforts to improve financial-sector competition, deepen bond markets and reduce transmission bottlenecks.

The present moment offers India a rare opportunity. Historically, the country has battled structurally higher inflation than many peers, forcing interest rates to stay elevated and limiting the space for counter-cyclical policy. Today’s combination of low inflation, healthy growth and ongoing tax and supply-side reforms opens the door to a different trajectory — but only if the window is used well.

Turning this disinflation into a durable advantage requires three parallel moves. First, supply-side reforms must keep pace: investment in logistics, cold chains, storage and agricultural productivity can make food prices less volatile over time. Second, tax policy stability matters. The GST rationalisation has shown that smart rate design can support both macro stability and administrative simplicity; constant tinkering would undermine those gains. Third, the RBI must strengthen its communication and credibility, explaining clearly how it interprets data, what it is watching, and how it intends to navigate the trade-off between growth and inflation.

For now, the story of India’s inflation is one of an economy that has earned breathing room but not certainty. The RBI’s challenge is less about reacting to a single 0.25% print and more about managing expectations, improving transmission, and sequencing policy so that today’s rare disinflationary window translates into lower structural inflation and sustainably lower interest rates over the decade ahead.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart