Nominal GDP growth is the economy’s “top-line.” It captures both real activity (volumes) and price effects (inflation). When nominal growth is strong without runaway inflation, it usually shows up as faster income creation, better employment momentum, healthier tax collections, and rising corporate sales. When it weakens, the stress often appears everywhere at once households feel a squeeze, businesses hesitate on expansion, and policymakers start leaning more on liquidity and support.

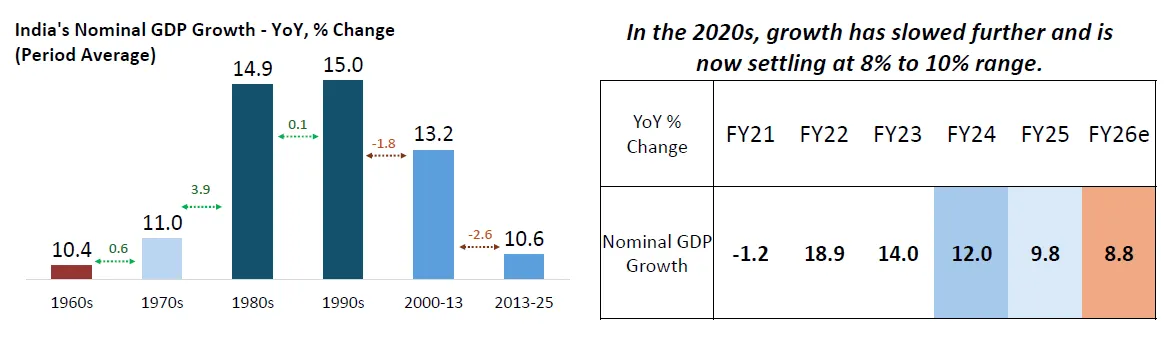

India’s nominal growth has clearly downshifted over time. After the high-growth decades that benefited from reforms and a favourable cycle, nominal growth averaged around the mid-teens in the 1980s–2000s phases, and then slipped materially in the post-2013 period. A key point is not just that the average is lower, but that the ceiling has lowered too: since FY14, outside of the post-COVID base-effect spike, nominal growth has struggled to sustainably exceed the low-teens.

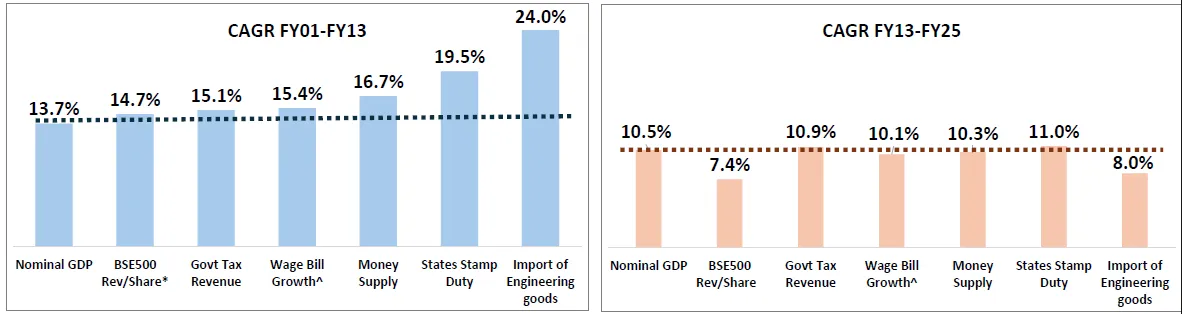

That downshift is visible - corporate revenue growth, tax collections, wage bills, money supply growth, stamp duties, and core goods imports all tell a similar story. The economy is expanding, but the pace looks more like a steady grind than a boom.

If policymakers want inflation around 4%, then 10% nominal growth mechanically maps to roughly 6% real growth. That may be decent in isolation, but it can be underwhelming for a country trying to maximise a demographic window, lift labour-force outcomes, and absorb a large working-age population into productive employment. The question is not whether 6% real growth is “good”; it’s whether it is enough for India’s ambitions and constraints.

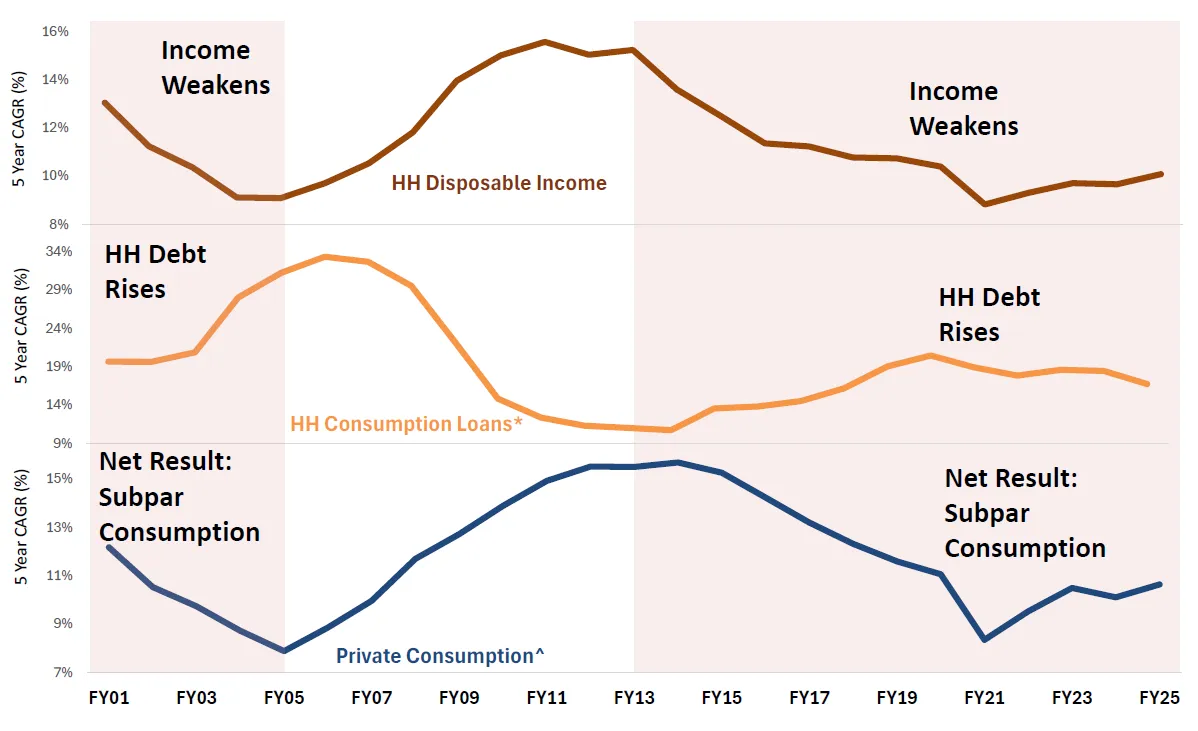

One of the clearest channels behind the nominal slowdown is consumption. Household spending can remain resilient for a while even when income growth weakens because credit can bridge the gap. But that bridge has a toll: the longer debt replaces income, the more future consumption is pre-committed to repayments, and the more sensitive households become to rate cycles and job uncertainty.

The key pattern is a divergence between the growth rate of household incomes and the growth rate of household borrowing for consumption. When consumption loans compound faster than disposable income over multi-year periods, the economy may still look “okay” in the moment. Retail demand holds up, services don’t collapse, and discretionary categories can remain buoyant. But the underlying quality of demand deteriorates because it becomes less self-funded.

Over time, this dynamic can create a feedback loop. Slower income growth restrains sustainable consumption; weaker consumption reduces business confidence and visibility; softer visibility discourages private capex; and weaker capex limits the job and wage engine that would have repaired consumption in the first place. The loop doesn’t require a crisis to be damaging—its main cost is lost compounding.

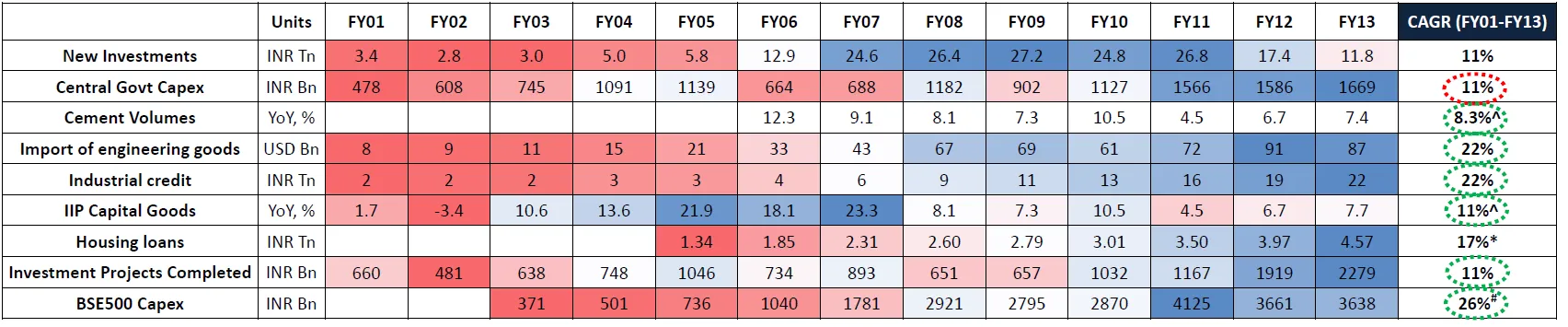

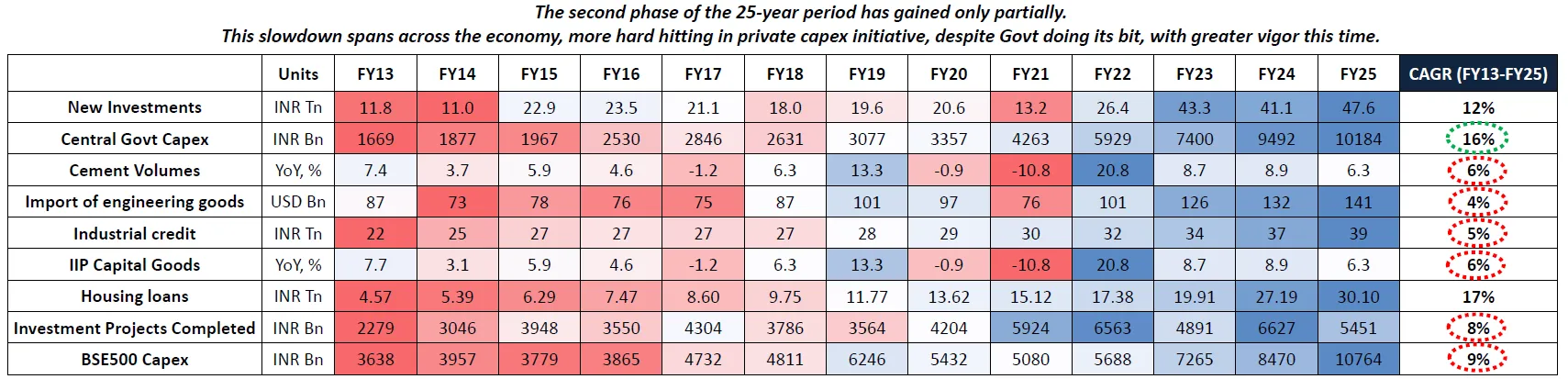

Government capex has been a relative bright spot, growing faster and more consistently than many private indicators. Yet several real-economy capex trackers such as industrial credit, capital goods activity, engineering goods imports, and broad corporate capex look far less energetic than they did in the earlier high-momentum period.

This matters because not all capex creates the same second-order effects. Investment that raises productive capacity logistics, freight efficiency, industrial corridors, energy reliability, manufacturing ecosystems - tends to pull employment, wages, exports, and tax buoyancy along with it. Investment that is more consumption-adjacent can improve quality of life and urban mobility, but it may not lift the economy’s ability to produce tradables, substitute imports, or generate mass employment at the same scale.

The consequence is visible in outcomes: wage growth remains less supportive, corporate sales growth struggles to regain earlier highs, and exports do not become the powerful second engine they need to be. In a world where India is trying to grow into a much larger economic footprint, capex that does not meaningfully raise productivity can leave the country with impressive assets but an economy that still feels “tight” in incomes and jobs.

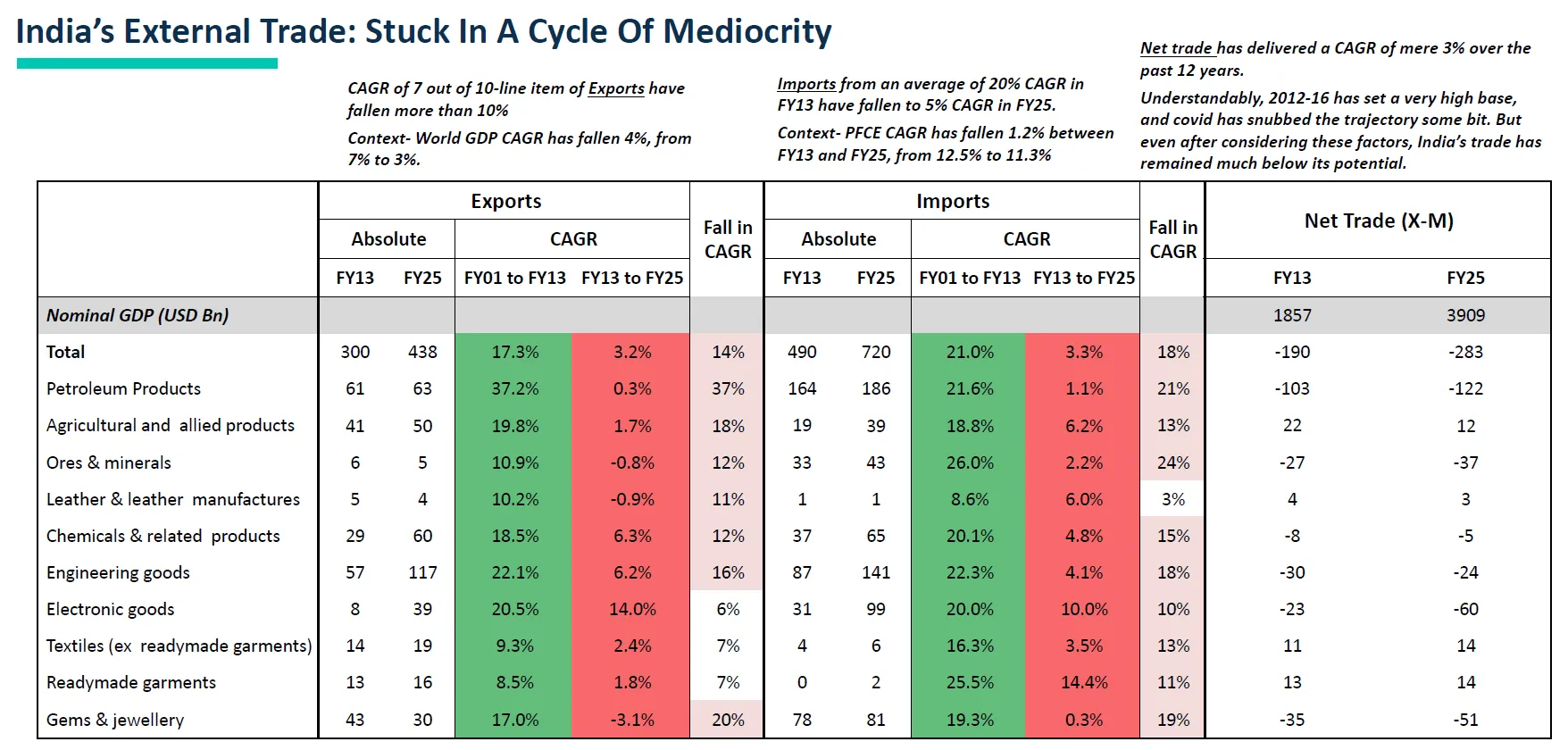

India’s external sector has 2 contrasting stories.

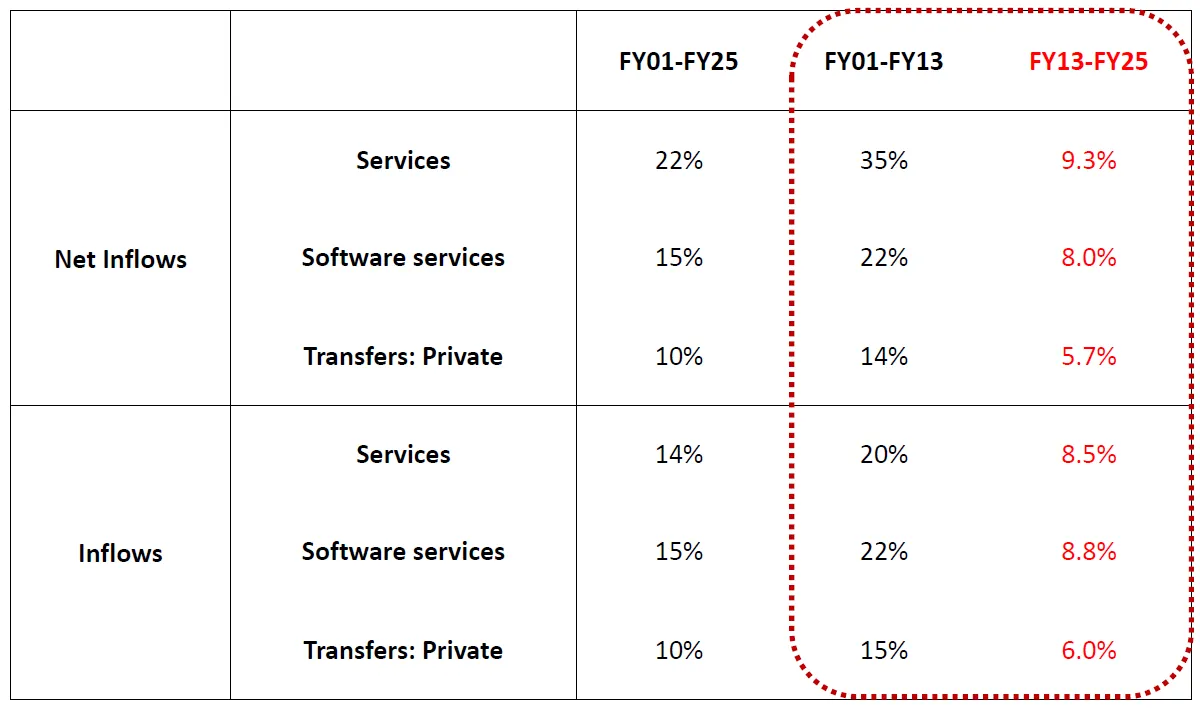

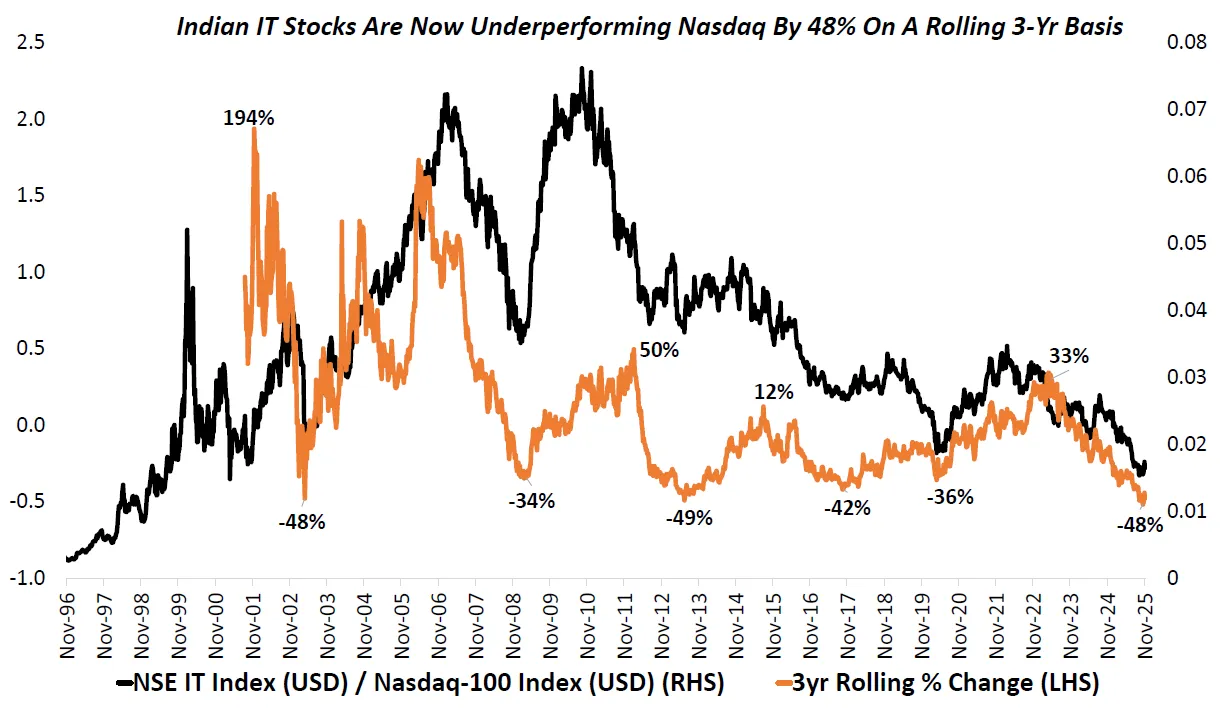

The first is a genuine success: services exports. Over a long runway, services especially IT and IT-enabled services have delivered an outsized prosperity impulse. They have generated large foreign-currency inflows, underpinned high-quality urban employment, and supported consumption and housing demand in ways few other sectors have matched.

The second story is far less flattering: goods trade has remained stuck in mediocrity. Export momentum has faded, import growth has also cooled, and the net trade picture has not delivered the kind of sustained positive impulse that a rising manufacturing power would normally aim for. This is not merely an accounting issue; it shapes currency dynamics, influences the stability of external financing, and ultimately affects domestic policy room.

The third, and perhaps most important, point is that the slowdown is not subtle. In the post-FY13 period, multiple export line items show meaningful decelerations in growth rates compared with the earlier decade. Even allowing for high bases and global slowdowns, the pattern suggests India is not extracting as much as it could from global demand, particularly in categories where scale, logistics, and ecosystem depth matter.

When goods trade fails to accelerate meaningfully, the burden on services becomes heavier. That can work for a while, but it increases concentration risk: if services exports slow (even to still-respectable single-digit USD growth), the knock-on effects are felt across domestic demand, real estate, and the broader corporate earnings pool.

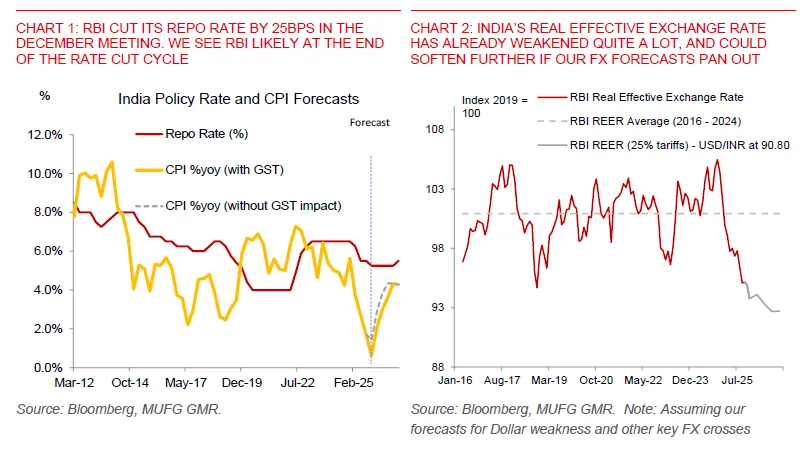

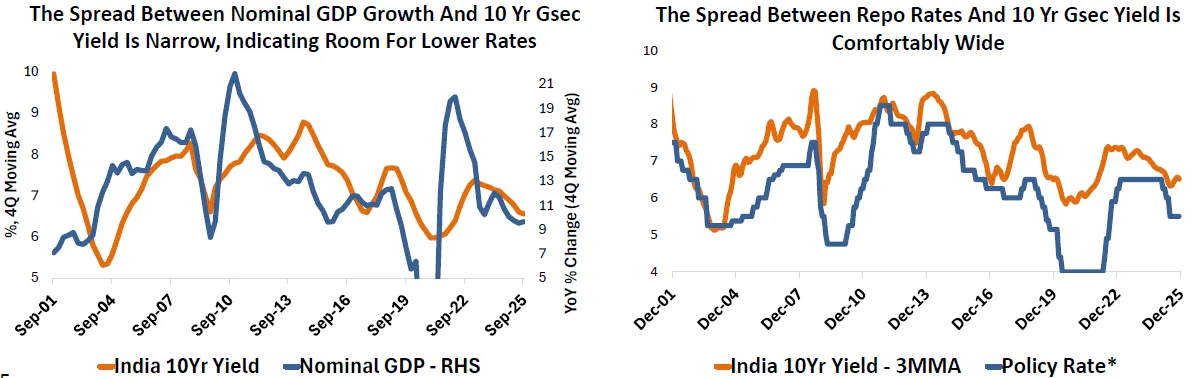

By December 2025, monetary policy was responding to this mix of patchy growth, contained inflation, and evolving external pressures. The central bank cut the repo rate by 25 basis points to 5.25% while keeping its stance neutral. The signal embedded in that combination is nuanced: policy is willing to support growth and liquidity conditions, but it is not declaring an all-out easing regime.

Liquidity actions reinforced the message. Alongside the rate cut, the system saw sizable liquidity injections: open market purchases of government bonds and an FX buy/sell swap operation. Easier liquidity can stabilise domestic conditions, but it can also coincide with a weaker currency if the balance of payments is under strain. A central bank can choose to smooth volatility without defending a specific level. When that happens, the currency can drift weaker over time even if volatility remains contained.

From an investor’s perspective, this environment can be unusually constructive for bonds. When growth is uneven, inflation is subdued, and bond supply pressures are not exploding, longer-duration government bonds can offer a combination of carry and potential capital gains.

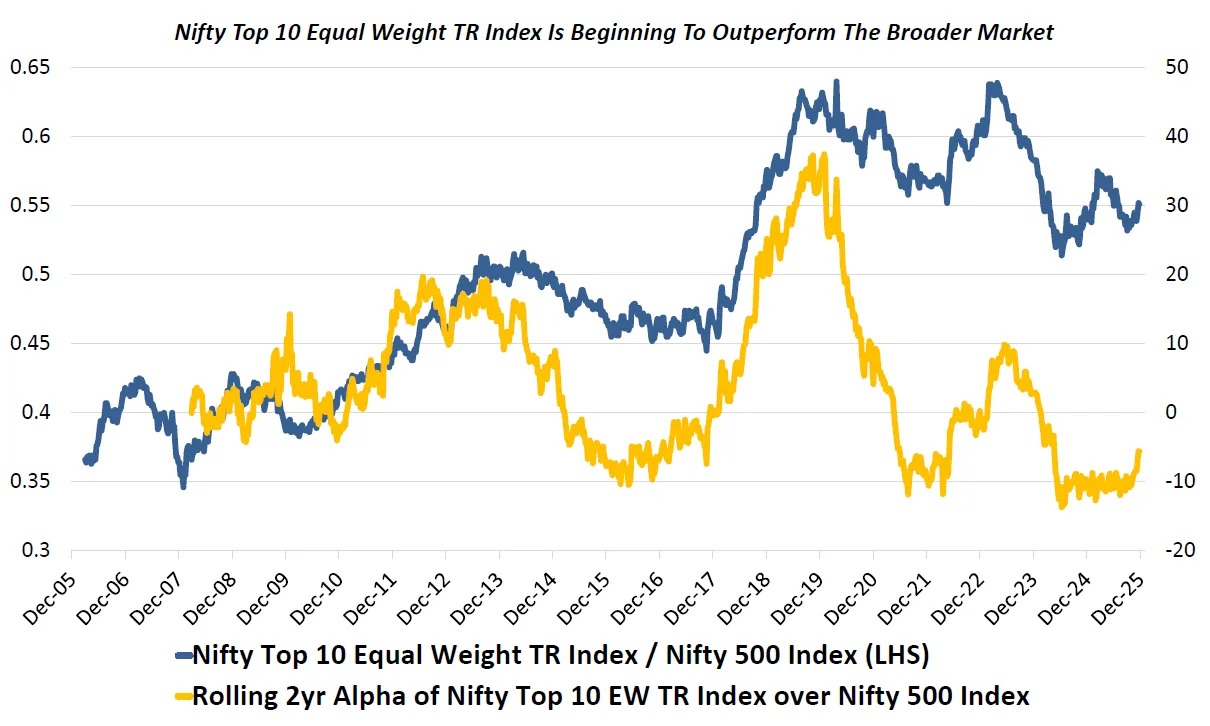

Large cap companies' share of total market capitalization fell to unusually low levels, and their relative price performance weakened versus the broader market. That combination matters because it is typically unsustainable; when the largest names become both under-owned and under-performing, the bar for positive surprise drops sharply. The recent trend suggests the inflection is already underway, with the top cohort beginning to outperform again versus broader benchmarks.

A key driver of that shift is the nature of incremental market-cap supply. A large portion of new listings has come at demanding valuation multiples, often above 50x trailing earnings, despite a comparatively thin profitability base. When new issuance adds market cap without adding commensurate earnings power, it can distort where “growth” appears to be and compress forward returns. Highly profitable large caps become a relative-value trade even if they do not look “cheap” in absolute terms.

This is also why the largest stocks can become attractive precisely when they feel unpopular. When top-10 and top-50 shares of total market capitalization hover near historical lows, the allocation pain of owning large caps is already embedded in portfolios. If the market’s next phase prizes earnings resilience, balance-sheet quality, and liquidity, large cap companies do not need heroic growth, they only need to disappoint less than the frothier parts of the market.

One of the more interesting late-cycle signals is what happens to largecap defensives. When risk appetite cools, sectors with durable cash flows, global revenue exposure, and strong balance sheets can become relative winners even if absolute returns are muted.

By late 2025, largecap Indian IT looked underowned and meaningfully derated compared with earlier phases. The sector’s weight in major indices was depressed, negative sentiment was widespread, and performance had lagged global tech benchmarks sharply over rolling periods. Yet the underlying businesses still showed strong return metrics and remained central enablers in enterprise technology shifts, including the operationalisation of generative AI.

IT does not need to become an explosive bull market leader to matter. In an environment of narrow breadth, heavy new-issue supply, and earnings expectations that may be too optimistic for the broader market, an underowned, cash-generative sector can serve as ballast. If valuations compress further, it can even flip from a weakness to opportunity, but that requires a clearer margin of safety.

India is still growing, but nominal momentum has cooled; consumption is more credit-dependent than it should be; private capex is not yet delivering the scale of productive expansion needed; and external balances look more constrained than the growth narrative implies.

When nominal growth settles into an 8–10%, compounding becomes less forgiving. Mistakes in allocation can carry a bigger opportunity cost than before. The economy can still perform well, but it must earn it through productivity gains and export capability rather than relying on broad cyclical tailwinds.

For policy, the course correction is conceptually simple but politically hard. Tilt investment toward productive capacity, not just visible consumption infrastructure; make it easier for private capex to commit for long horizons; and deepen the channels that attract stable, long-term foreign capital without overheating valuations.

For investors, this is not a market environment that rewards indiscriminate risk-taking. It rewards discipline and a strong understanding of fundamentals, along with macro variables such as currency risk.

The most powerful lever for lifting the nominal growth ceiling is improving the economy’s ability to produce tradables and scale employment. That requires a sharper focus on logistics efficiency, freight capacity, industrial ecosystems, and the kind of infrastructure that reduces unit costs for manufacturers and exporters.

A productive-capacity tilt also supports wages more directly. When investment creates scalable jobs, wage bills grow in a way that is less dependent on household borrowing. Consumption becomes self-funded again, which improves demand quality and stabilises the business cycle.

The real prize is a virtuous loop: stronger productive capex lifts exports and jobs; better jobs lift consumption; stronger consumption improves capex visibility; and improved external competitiveness stabilises the currency and reduces the “no free lunch” trade-offs in monetary policy.

Patchy growth and low inflation can create attractive opportunities for bonds, particularly when the yield curve and duration offers meaningful returns. Bonds perform best when growth is uneven and policy is supportive.

The stock market is signalling that breadth risk is real. Largecaps can regain relative appeal not because they are cheap, but because they offer defensiveness and liquidity when the marginal dollar becomes more cautious.

A controlled but persistent Indian currency exchange drift is not inconsistent with a stable domestic market. If the balance of payments is under strain and capital inflows are less supportive, currency weakness becomes part of the adjustment.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart