by Siddharth Singh Bhaisora

Published On Dec. 7, 2025

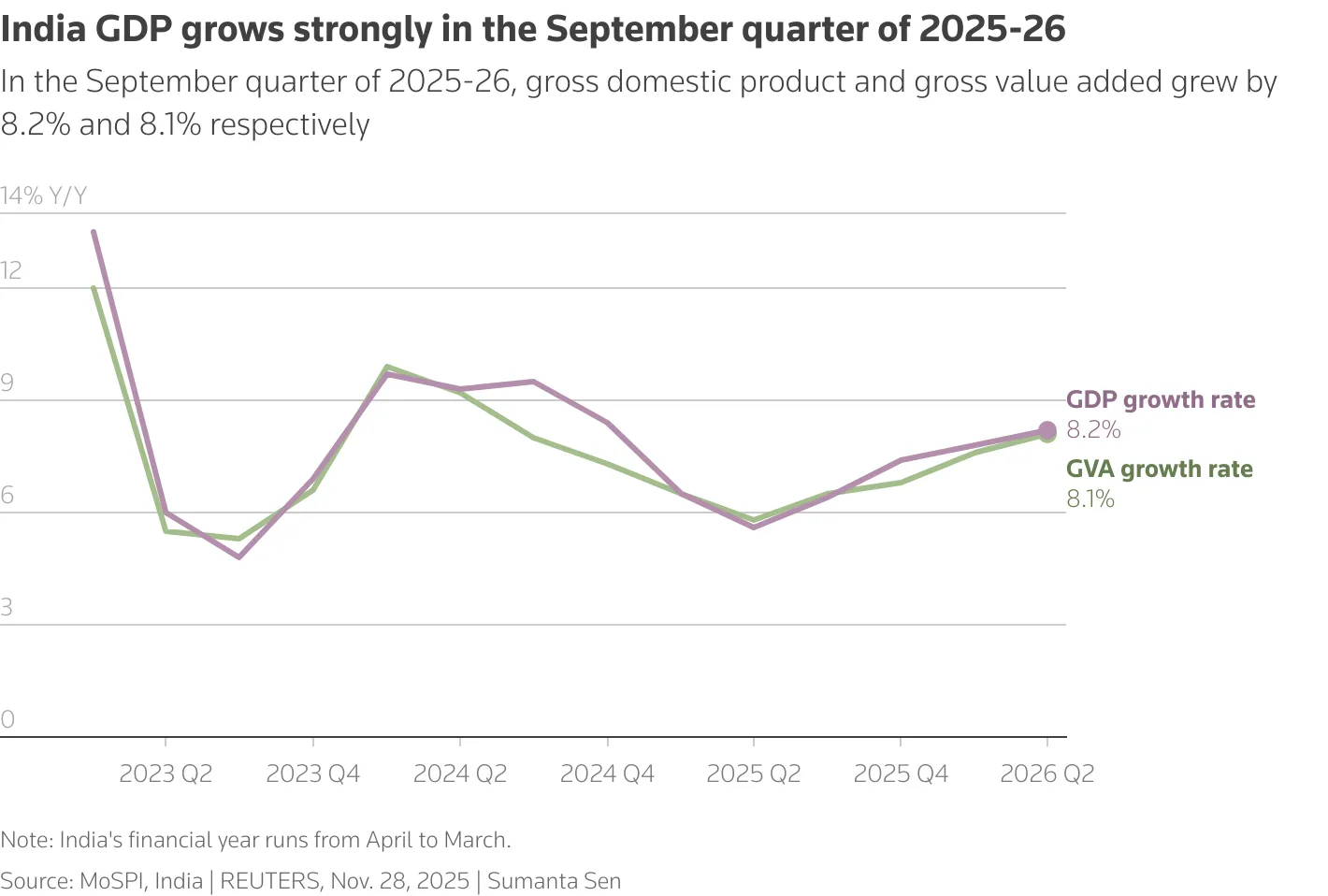

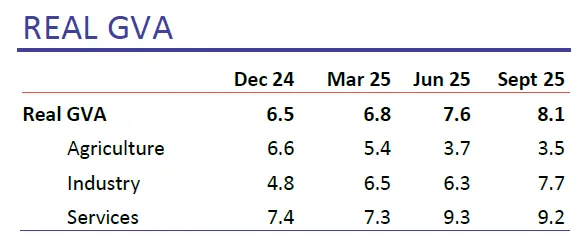

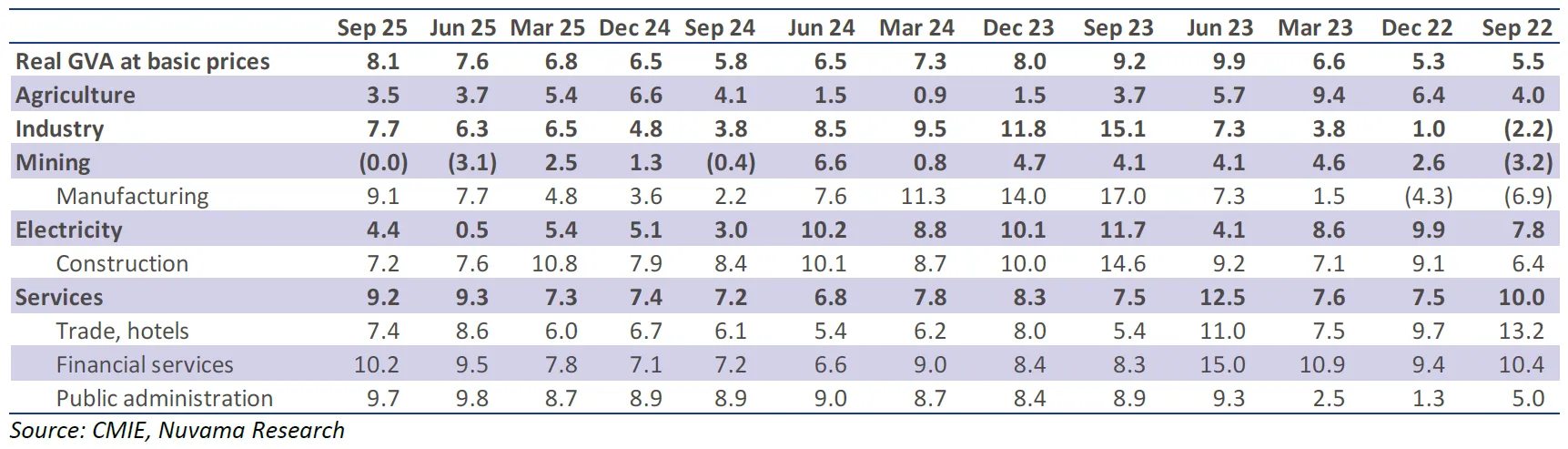

India’s latest national accounts data portray an economy growing at an enviable clip. According to the National Statistical Office, real GDP grew 8.2% year-on-year in Q2 FY26, taking growth in the first half of FY26 to around 7.6–8.0% compared with roughly 6.1% in the same period a year earlier. On the surface, this reinforces the popular narrative of India as the standout large-economy growth story in a slowing world. Real gross value added (GVA) is estimated to have risen by just over 8% in Q2, broadly in line with headline GDP, suggesting that most sectors of the real economy are participating in the expansion.

On the demand side, private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) remains the central pillar of growth. Real consumption is estimated to have increased by close to 8% in Q2, with its average in the first half of the year around 7–7.5%. Investment, as measured by gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), has also grown in the mid-single digits, roughly 7–7.5% in real terms. Government consumption, by contrast, has actually contracted in the latest quarter as the Union government front-loaded capital spending and tried to keep revenue expenditure under control.

External demand is contributing modestly. Exports of goods and services grew at about 5–6% in real terms in the first half, helped by robust services exports and some front-loading of goods shipments to the United States ahead of higher tariffs. Imports, however, grew faster, near 12%, driven by precious metals and non-oil non-gold imports, widening the trade deficit. While the export impulse has been supportive so far, there are signs of softening as US-bound shipments start to feel the impact of tariff hikes and global demand slows.

Beneath the aggregate, the sectoral story is one of manufacturing and services carrying the baton while agriculture and mining lag. Real GVA data show agriculture growing around 3.5% year-on-year in Q2 FY26, slower than previous year but still respectable given subdued food prices. Mining output has effectively stalled, with real mining GVA roughly flat on a year ago and nominal mining growth actually in contraction territory, affected by weather-related disruptions and weaker commodity prices.

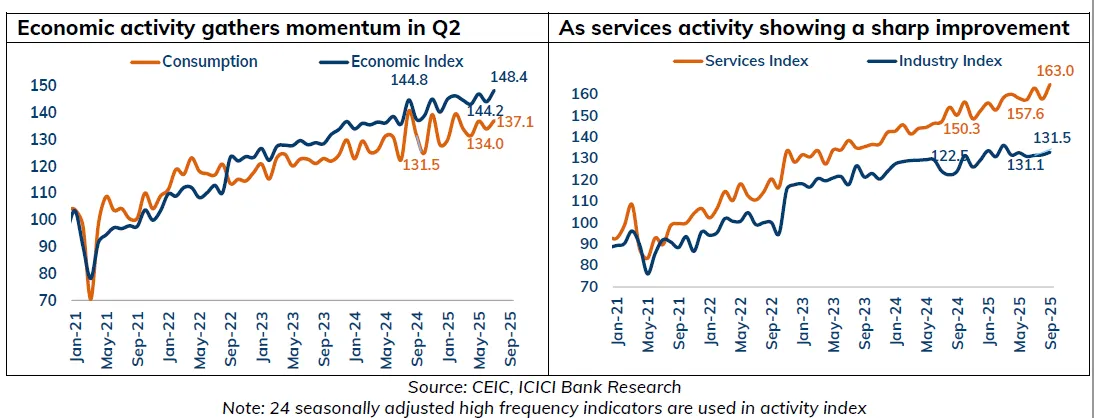

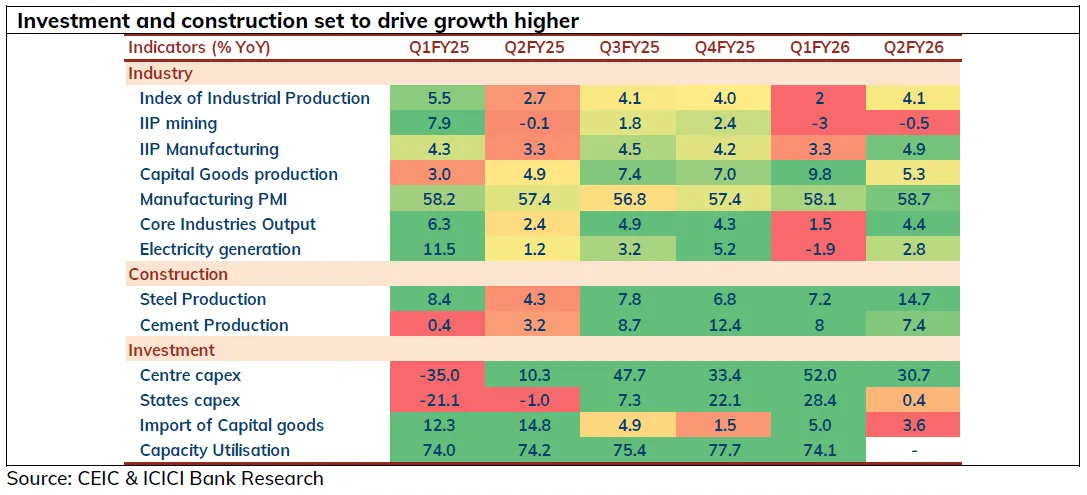

Industry excluding mining has fared better. Manufacturing GVA has grown by about 9% in real terms, its strongest print in six quarters, aided by a soft base and improved margins in automobiles, machinery, and basic metals. Construction activity remains robust, growing above 7%, supported by central government capital expenditure, infrastructure projects, and continued urban real estate activity. High-frequency indicators such as steel consumption, cement output and the manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) all corroborate solid industrial momentum in the quarter, even if they do not quite match the exuberance of the national accounts numbers.

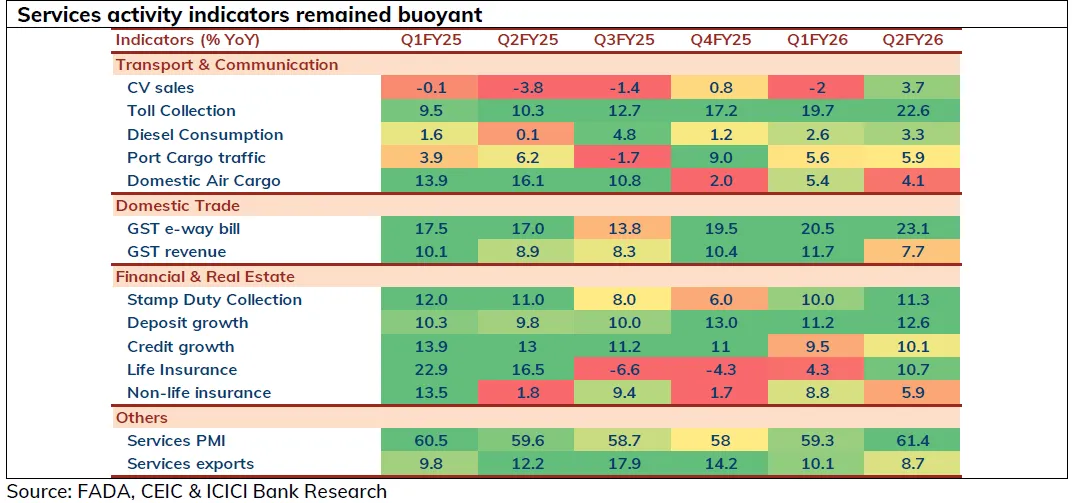

Services remain the backbone of the economy, posting real growth slightly above 9% in Q2. Within services, financial and real-estate services have grown in double digits, helped by healthy bank credit growth, rising deposits and steady insurance premiums. Public administration and defence continue to grow at around 9–10%, anchored by government salaries and welfare schemes. Trade, hotels, transport and communication have expanded in the upper single digits, though some sub-sectors such as tourism show signs of fatigue due to capacity constraints and erratic weather. Overall, the sectoral mix is consistent with India’s long-standing shift towards a services-heavy growth model, but with a welcome cyclical recovery in manufacturing and construction.

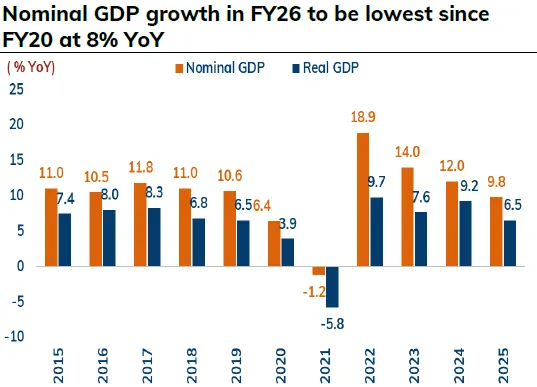

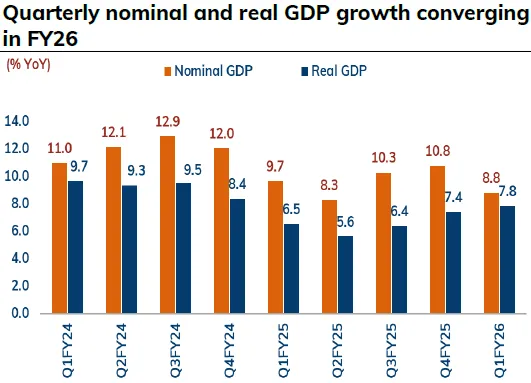

While real GDP prints make for impressive headlines, nominal GDP tells a more sobering story. Nominal GDP growth in Q2 FY26 is estimated at about 8.7%, almost unchanged from 8.8% in Q1 and well below the 11–12% norms that characterised the previous decade. For the year as a whole, several private-sector forecasters now expect nominal GDP growth to be only around 8%, the weakest since FY20. With the GDP deflator depressed by low wholesale price inflation and modest consumer price inflation, real growth appears strong even as the nominal economy lacks buoyancy.

This divergence between real and nominal growth is more than just statistics. Taxes, corporate revenues, household incomes and interest burdens are all denominated in nominal rupees, not inflation-adjusted terms. Nominal GDP has averaged roughly 10% over the past two years, which is only just back to its pre-Covid trajectory and significantly lower than the high-teens peaks seen during earlier inflationary episodes. From an investor’s perspective, equity earnings and nominal GDP tend to move together over time; a sub-9% nominal growth environment makes it difficult to sustain mid-teens earnings growth without either margin expansion or market-share shifts.

The low-deflator, high-real-growth combination also complicates monetary policy. With consumer price inflation projected around 2–2.5% in FY26 and wholesale prices even lower, real policy rates appear quite restrictive. Yet the GDP numbers suggest the economy is running hot, giving the Monetary Policy Committee little political room to cut rates. The result is a policy stance that looks tighter than warranted by nominal indicators but looser than headline real GDP would imply. Central bankers, like investors, are forced to look beyond the topline numbers to a wider dashboard of data before making decisions.

For the Union government, anaemic nominal growth is already visible in softer tax collections. Growth in combined direct and indirect tax revenues has slowed to under 3% in the first half of FY26 from nearly 12% in the corresponding period a year ago, despite increases in the tax base and better compliance. With fiscal deficit targets hard-wired into medium-term consolidation plans, lower-than-expected nominal GDP and tax buoyancy leave limited fiscal space for fresh spending initiatives or large counter-cyclical programmes in the event of a global slowdown.

From a corporate standpoint, national accounts data sit uneasily alongside reported results. For the Nifty-50 universe, sales growth over the last ten quarters has averaged close to 6% in nominal terms, far below the double-digit real GDP prints being recorded in the same period. This discrepancy is particularly acute in consumer-facing sectors, where listed company volumes and revenues point to only modest demand growth. If nominal GDP is growing in the high-single digits but corporate top lines are advancing at only mid-single digits, the implication is that either a large part of incremental demand is being captured by unlisted firms or, more plausibly, that macro numbers are overstating the true pace of expansion.

For investors in fixed income, low nominal growth and subdued inflation have mixed implications. On one hand, they cap bond yields by keeping inflation expectations anchored and reducing the supply of government paper relative to GDP. On the other hand, if markets begin to doubt the sustainability of growth or the quality of fiscal data, term premia can widen sharply. The recent hardening of the 10-year government bond yield to around 6.5%, alongside a weak rupee trading close to 90 per dollar, hints at a degree of scepticism among both domestic and foreign investors about the macro narrative, despite apparently benign inflation and strong real GDP growth.

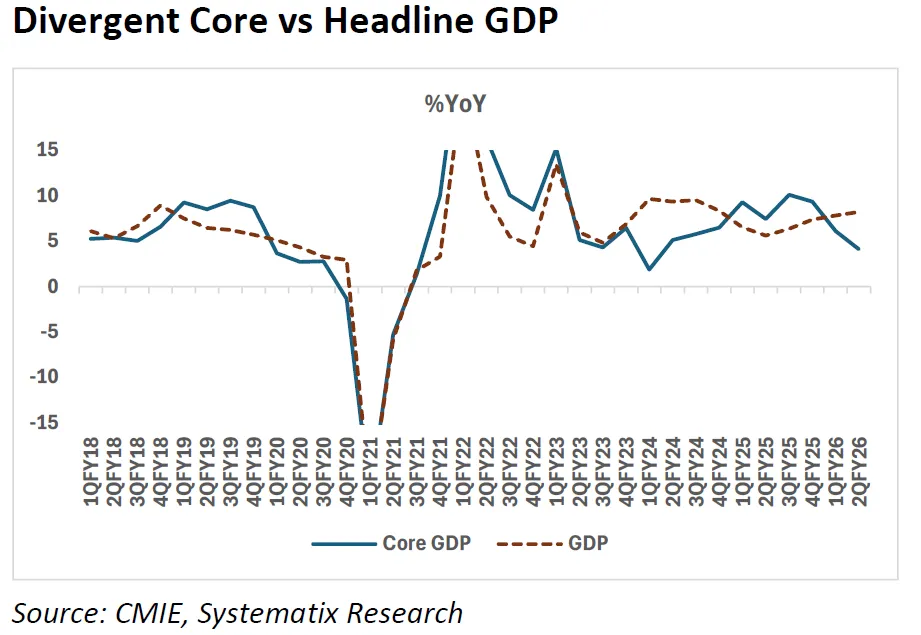

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of India’s GDP numbers today is the growing wedge between headline growth and what a range of high-frequency indicators, surveys and corporate data suggest. One way to formalise this is to look at “core GDP”, defined as real GDP excluding the statistical discrepancies that reconcile the production and expenditure approaches. Core GDP growth in Q2 FY26 is estimated at just over 4%, a nine-quarter low, compared with the 8.2% growth in headline real GDP. The difference is accounted for by a sharp rise in unexplained discrepancies, which effectively “top up” the official growth figure.

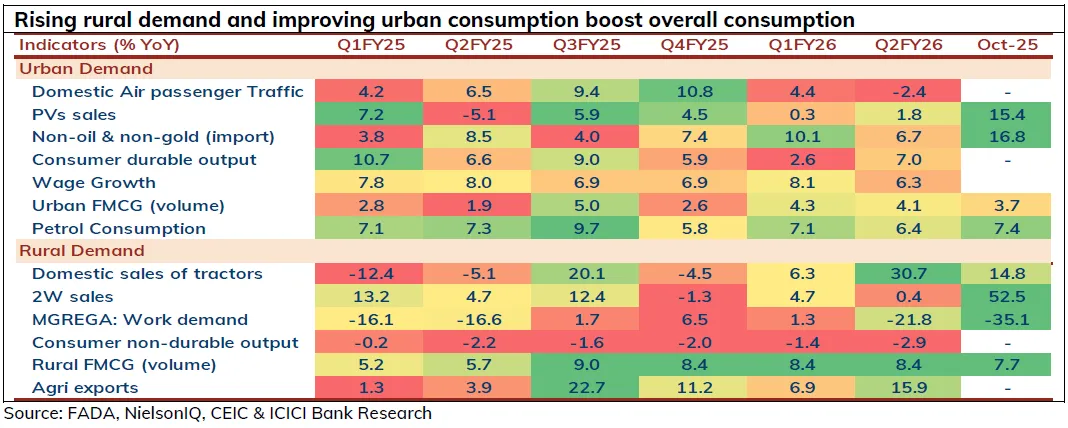

Consumption offers another example of this disconnect. The national accounts show real private consumption growing about 8% in Q2, yet production of consumer goods in the Index of Industrial Production rose less than 1% year-on-year over the same period, down from around 3% a year earlier. Fast-moving consumer goods companies report only low-single-digit volume growth in urban markets and somewhat stronger, but still moderate, growth in rural areas. Household surveys by the Reserve Bank of India point to cautious sentiment and heightened job insecurity, particularly among lower-income cohorts. On the credit side, incremental personal loans have slowed sharply, with the exception of loans against gold, a classic sign of household stress.

Investment data tell a similar story. While nominal GFCF is estimated to have grown a little over 8% in the first half of FY26, government capital expenditure (centre and states combined) has risen in the mid-teens, implying that private capex is either flat or declining in real terms. Bank lending to industry remains concentrated in working capital and refinancing rather than fresh project finance. Capacity utilisation in manufacturing has just about reached 74–75%, enough to support some brownfield expansion but not yet a full-fledged private investment cycle. Announced private projects have picked up, especially in power, cement and construction, but the lag between announcement and execution remains long and uncertain.

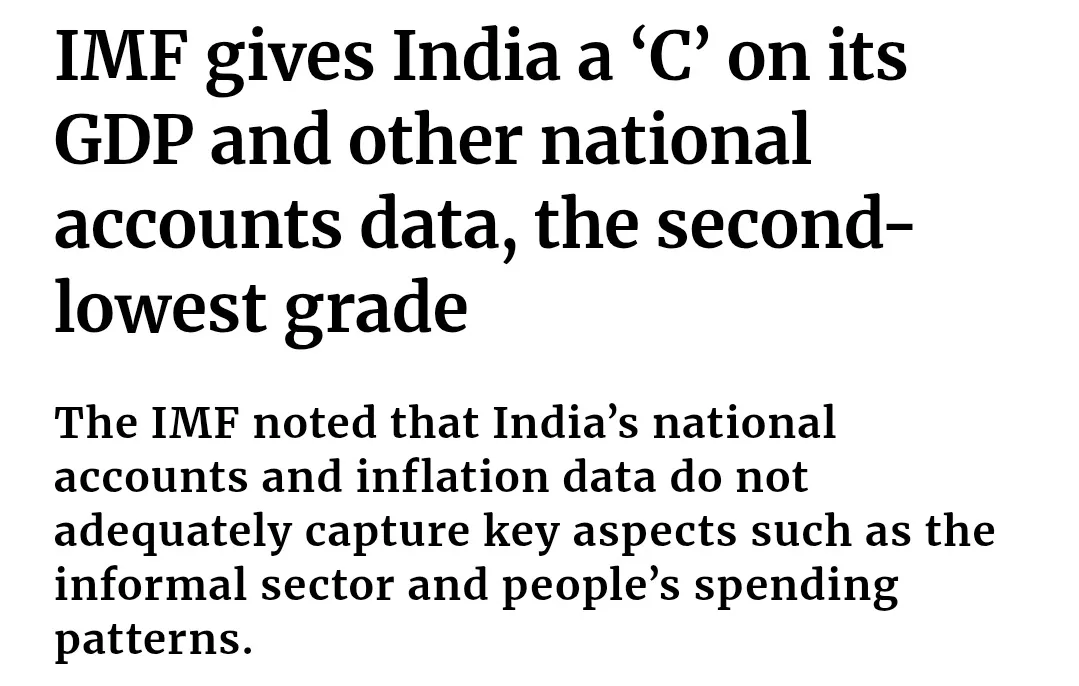

The growing gap between macro aggregates and micro realities has inevitably raised questions about data quality. The International Monetary Fund recently assigned India’s national accounts a “grade C” in its assessment of data adequacy for surveillance, citing concerns about the outdated base year, methodological opacity and particularly the large, variable discrepancies between production- and expenditure-side GDP estimates. While a “C” grade is not an indictment of the entire statistical system, it is a clear signal that users of the data should exercise caution and that the authorities need to strengthen underlying surveys and estimation methods.

For policymakers, unreliable GDP numbers can be more than an academic nuisance. If growth is overstated, the central bank may delay rate cuts for fear of overheating, even as households and firms experience weak income growth and tight financial conditions. Fiscal projections based on optimistic nominal GDP paths can lead to under-provisioning for deficits and debt, constraining policy flexibility when shocks hit. For regulators and planners, mis-measured sectoral output can distort everything from credit allocation norms to infrastructure planning, with real economic costs.

This does not mean dismissing GDP entirely, but it does require triangulating multiple sources and being open to the idea that the true pace of growth may be closer to 4–5% than the 7–8% being reported. Over time, persistent doubts about data can feed into risk premia on Indian assets.

Looking forward, most credible forecasts envisage some moderation in real growth in the second half of FY26. With central government capex heavily front-loaded—up more than 30% year-on-year in H1 but likely to slow or even contract in H2—and exports facing headwinds from weaker global demand and trade frictions, quarterly GDP growth could ease towards 6 - 6.5% in coming quarters.

On the monetary side, RBI has space to cut rates—real rates are high, inflation is subdued, and credit growth, while healthy, is far from excessive. Yet the political optics of easing in the face of 8% headline real growth and a still-wide current account deficit are tricky. The most likely outcome is a prolonged pause, with the RBI signalling that it stands ready to reduce rates if global conditions deteriorate or if domestic activity clearly slows.

On the fiscal side, the government will probably stick to a gradual consolidation path, relying more on expenditure reprioritisation and asset sales than large tax hikes, given the already heavy tax burden on formal households and businesses.

For the real economy, the GST cuts on select consumption items and regulatory easing for banks and NBFCs should provide some near-term support to demand, particularly in rural areas where two-wheeler and tractor sales have picked up after a long slump. Two consecutive good monsoons have lifted agricultural output by well over 6% in the current agricultural year, helping rural incomes even as low food inflation caps price realisation. Urban demand, however, remains more tentative, constrained by moderate wage growth and higher real interest rates. The balance of risks therefore points to a steady but unspectacular expansion, with growth outpacing most peers but falling short of the double-digit aspirations repeatedly voiced in policy circles.

The real growth story is not fictitious; India is genuinely growing faster than most major economies, with strong pockets in manufacturing, construction and services. However, the combination of weak nominal growth, questionable data quality and limited policy space argues for a discriminating, bottom-up approach rather than blind macro optimism. In such an environment, earnings visibility and balance-sheet strength matter more than top-down growth narratives.

Sectors tied closely to government capex and urban infrastructure—such as construction materials, select engineering companies and infrastructure financiers—are likely to feel the impact of any slowdown in public spending in H2, but their medium-term prospects remain supported by India’s structural investment needs. Export-oriented manufacturing faces near-term challenges from tariffs and global weakness but stands to benefit if global supply chains continue to diversify towards India over the next five years. Domestic consumption plays, particularly in discretionary categories, should be approached selectively, favouring firms with pricing power, strong brands and rural reach rather than those dependent purely on urban aspirational spending.

Above all, the GDP debate underscores the importance of building portfolios that are resilient to both upside and downside surprises in growth. This means balancing cyclical exposure with defensives, paying close attention to corporate governance and accounting quality, and tracking high-frequency indicators—tax collections, credit trends, freight volumes, power demand—alongside official GDP. India’s growth story remains compelling, but it is a story best read between the lines of the national accounts, not just in their boldface headlines.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart