by Siddharth Singh Bhaisora

Published On Dec. 9, 2025

The world thought chips were the bottleneck of the last cycle. It turns out the real choke point of the AI age is much narrower: memory. DRAM, NAND, and especially high-bandwidth memory (HBM) have quietly become the scarcest inputs in the most important computing build-out since the internet. For Indian investors, this is not a distant semiconductor soap opera. It will shape margins in consumer electronics, cloud, AI infrastructure, Indian policy on manufacturing, and, ultimately, returns on Dalal Street.

Watch the full video here:

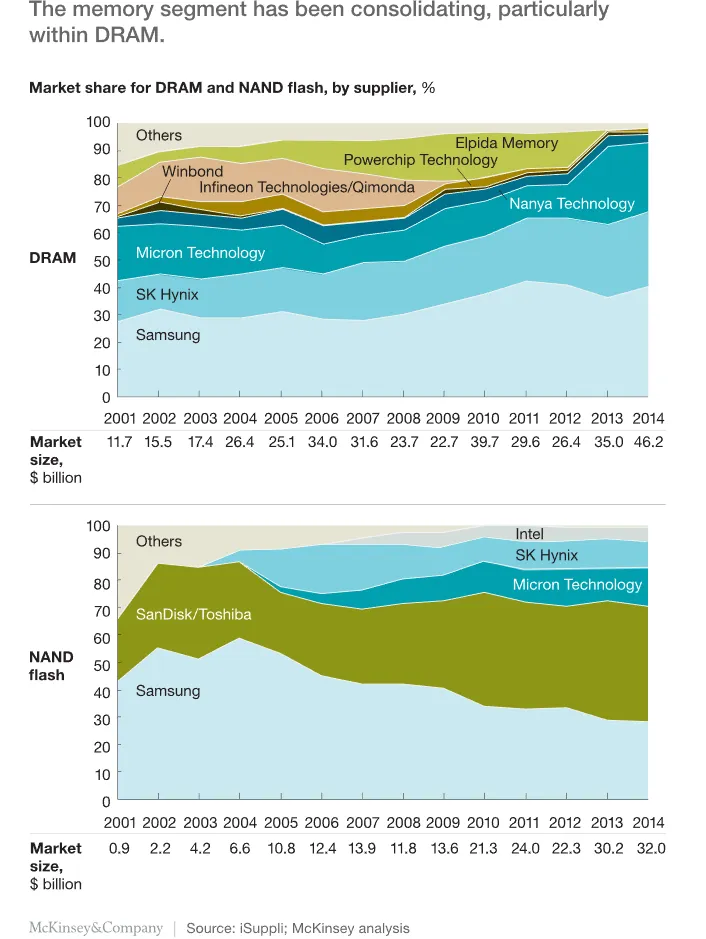

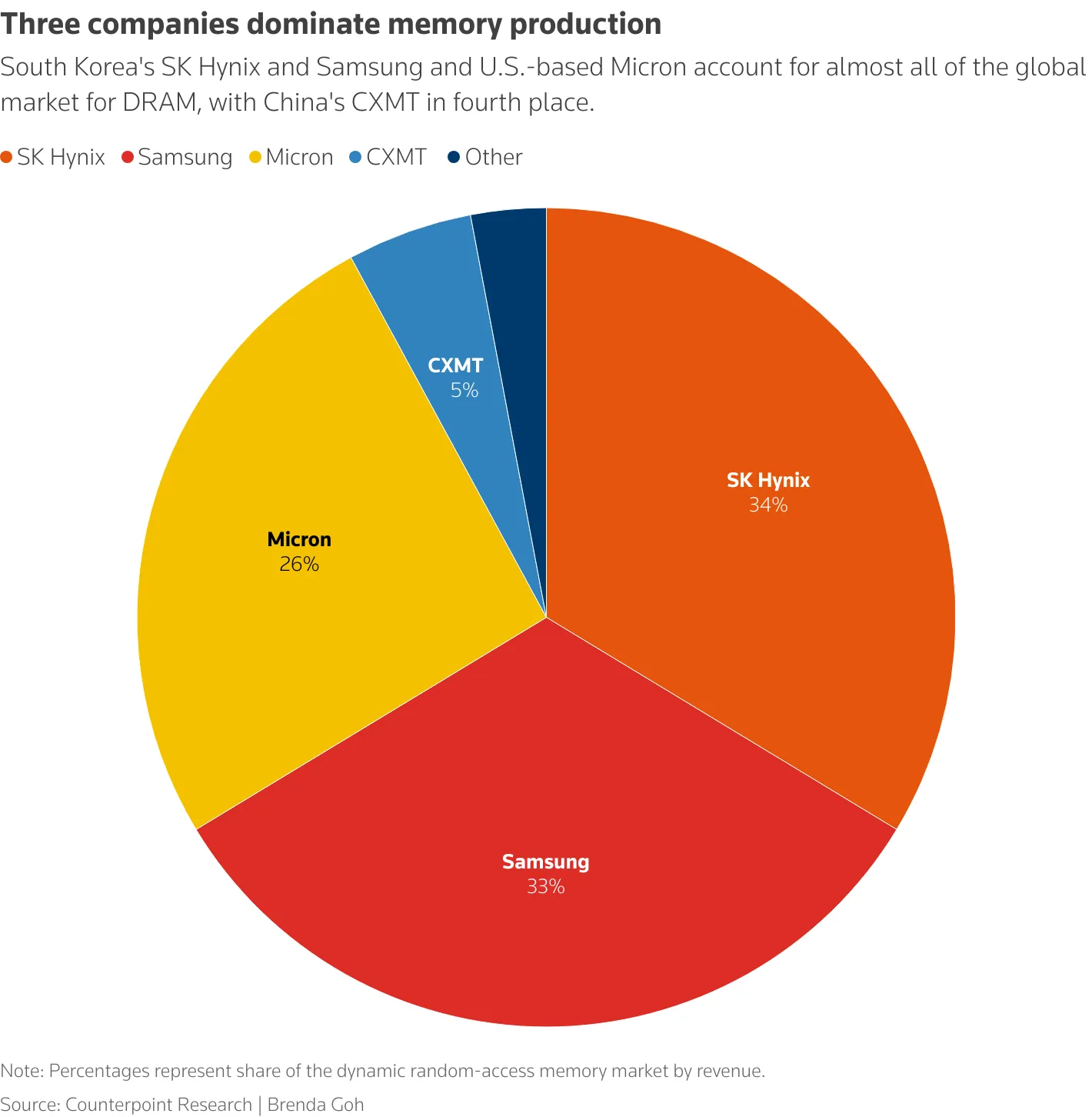

For most of the last four decades, memory has been the graveyard of semiconductor dreams. In the 1980s, more than 20 companies made DRAM. Today, three firms—Samsung Electronics, SK hynix, and Micron—dominate the market after repeated waves of bankruptcies and consolidation. The reason is simple: memory is a commodity. When times are good, everyone adds capacity; when demand slows, prices collapse, wiping out weaker players.

Even before the AI boom, memory was a quarter of the global semiconductor market by revenue. An Omdia study showed DRAM and NAND together accounted for roughly 25% of worldwide semiconductor sales around 2020.That base has since grown. One recent estimate pegs the standalone DRAM market at about USD 115.9 billion in 2024, rising to USD 121.8 billion in 2025 and almost USD 194 billion by 2032, with Asia-Pacific already holding around 45% of the market. When you add NAND, the combined memory market is projected at roughly USD 171.6 billion in 2024, rising towards USD 287.5 billion by 2033.

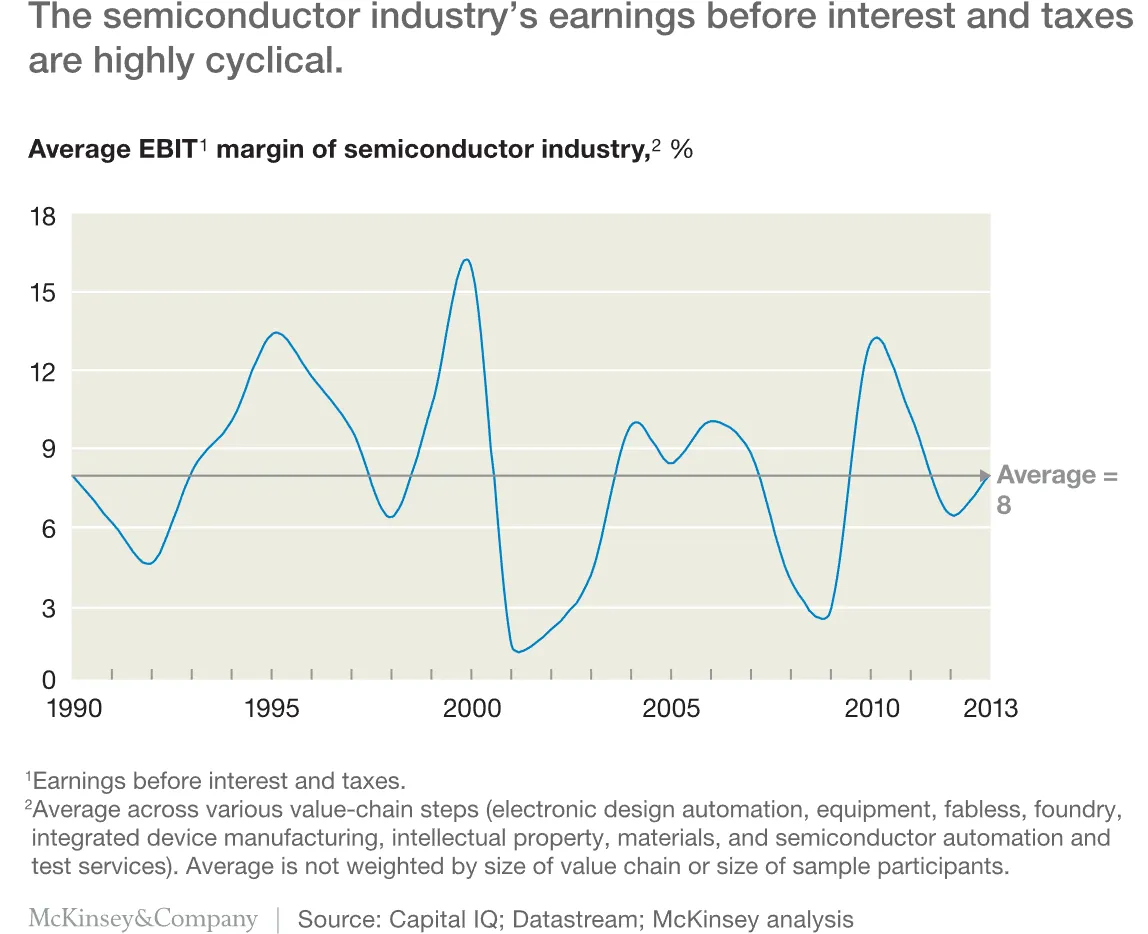

The AI wave has turned this inherently cyclical industry into something closer to a “supercycle”. Training and running large language models is extraordinarily memory-hungry. AI servers carry several times the DRAM and HBM content of traditional cloud servers. At the same time, PC and smartphone demand has recovered from its post-pandemic slump. Capacity that was originally planned for general DRAM and NAND is now being diverted into more profitable HBM. The result is a structural shortage, not just a normal up-cycle.

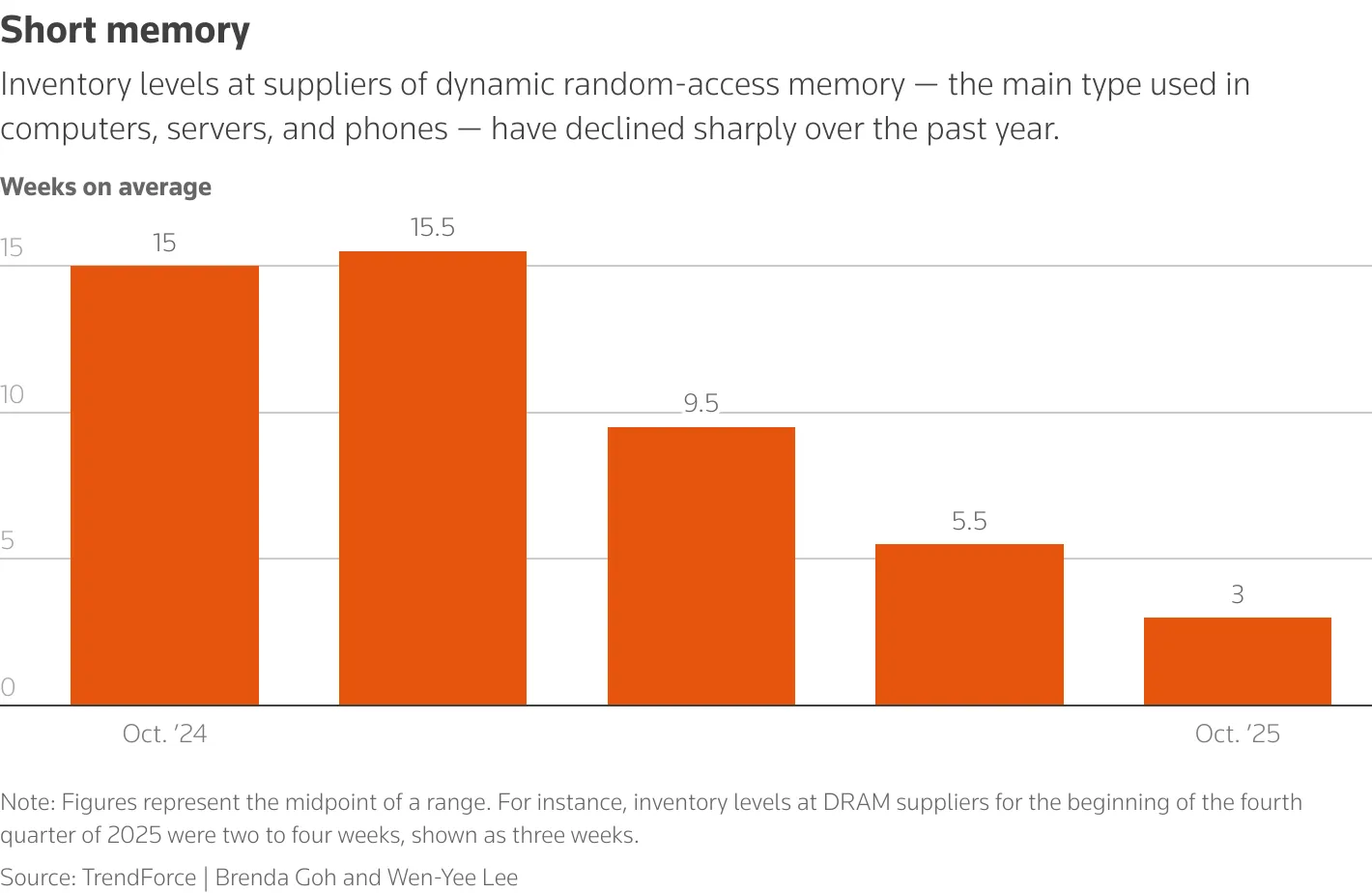

Over the last year, the global market has moved from surplus to outright scarcity at record speed. Industry data suggests DRAM prices are already up roughly 50% in 2025, with forecasts of another 30% rise in the fourth quarter and an additional 20% in early 2026. Another analysis points to a staggering 171.8% year-on-year surge in DRAM prices by the third quarter of 2025, one of the sharpest increases ever seen in memory. In some segments, server memory modules are on track to cost twice as much by the end of 2026 as they did at the start of 2025. Inventory levels for DRAM have declined sharply in the last 1 year.

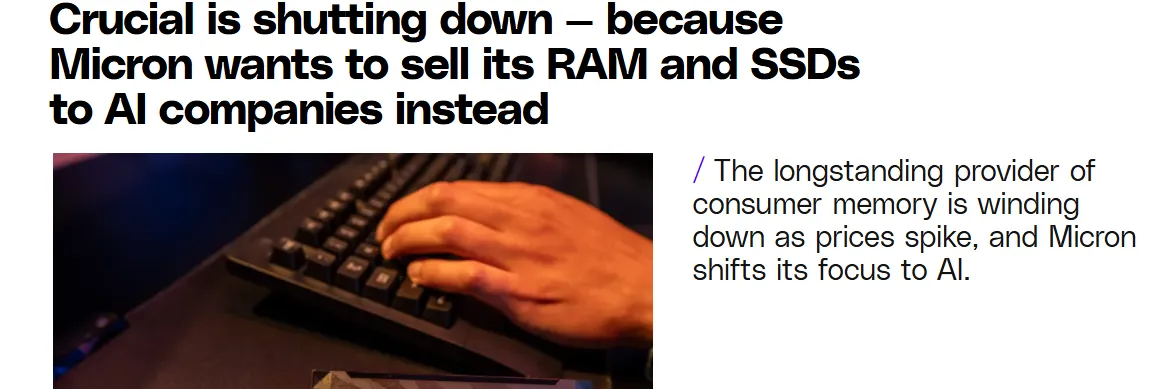

One example of this supply crunch is that, Micron has just recently shut down its 29 year old consumer-focused business and shifted its focus to sell memory products to AI companies.

Industry data suggests DRAM prices are already up roughly 50% in 2025, with forecasts of another 30% rise in the fourth quarter and an additional 20% in early 2026.

There is a genuine supply chain crisis.

A recent Reuters report describes a genuine supply chain crisis: AI data-center operators and cloud giants are placing open-ended orders for DRAM and HBM, while smartphone makers and PC OEMs are told to accept rationed allocations and higher prices. In some product categories, memory prices have already doubled. Suppliers warn that significant new capacity will not come online until 2027–2028. That is not a normal inventory cycle; it is a multi-year structural mismatch between demand and physical manufacturing capability.

HBM sits at the heart of this crisis. Unlike conventional DRAM, which is packaged on simple PCBs, HBM stacks multiple layers of DRAM vertically and connects them through advanced interconnects to GPUs or custom AI accelerators. This provides dramatically higher bandwidth and lower latency—exactly what training and inference workloads demand.

But that performance comes at a cost. HM is far more complex to fabricate and package, requiring cutting-edge process nodes, advanced 2.5D/3D packaging lines, and extremely tight tolerances. In practice, three companies—Samsung, SK hynix, and Micron—control the bulk of HBM production, while China’s ChangXin Memory Technologies (CXMT) is still catching up technologically and holds only a small share of the broader DRAM market. Building new HBM capacity is not like adding another shift in an assembly plant. It takes years, billions of dollars in capex, and stable access to lithography, materials, and packaging tools that are themselves in short supply.

Because HBM yields are still evolving and demand visibility is high, memory makers have every incentive to prioritise pricing discipline over aggressive capacity additions. Unlike previous cycles, balance sheets are stronger, industry concentration is higher, and management teams are more focused on margins than on sheer market share. That is good news for their shareholders, but bad news for downstream buyers hoping for a quick relief from high prices.

The immediate losers from the memory squeeze are obvious: device makers who cannot pass on higher costs. Smartphone brands like Xiaomi and Realme have already warned of price hikes and product delays due to memory shortages. Some retailers in Asia are reportedly rationing consumer memory products to discourage hoarding and arbitrage.

In the data-center world, the shock is subtler but more profound. AI infrastructure is hitting a new bottleneck: not GPUs, but system memory. Server configurations with 1–2 TB of DRAM are becoming common for large AI clusters, and the incremental cost of memory now meaningfully alters the economics of training and serving models. Industry analyses already talk of “memory inflation” as a new structural cost line in AI, one that operators did not fully bake into their earlier business models. For hyperscalers, this means either absorbing margin pressure, raising prices for AI services, or both. For smaller AI startups, it means a higher bar for achieving viable unit economics.

As always in semiconductors, the supply crunch is not just a story of prices and profits; it is a story of power. The memory market is now effectively a four-cornered contest between South Korea, the United States, Japan, and China, with Taiwan’s foundries and ASML’s lithography tools as indispensable enablers.

South Korean giants Samsung and SK hynix still dominate both DRAM and NAND. Samsung leads the global NAND market with roughly 32% share as of mid-2025, while SK hynix has pulled ahead in HBM, supplying a large portion of Nvidia’s HBM needs. Micron, long the smaller player, has used the AI cycle to reposition itself: it surprised the market by launching competitive HBM3 products and has reportedly secured multiple HBM3E design wins with leading GPU makers, with much of its 2026 output already contracted.

China, despite pouring billions into its memory champions, has struggled to capitalise on the current shortage. Reuters’ Breakingviews notes that CXMT still holds only about 5% of the DRAM market and is roughly three years behind South Korean rivals in technology. Its DDR5 chips lag in efficiency, and looming U.S. export restrictions could further slow progress. That means China remains heavily dependent on foreign memory for its own AI ambitions, a strategic vulnerability in an era of escalating tech sanctions.

Governments have understood that whoever controls memory capacity controls a critical lever in the AI race. Japan has emerged as a key beneficiary. Micron plans to invest about 1.5 trillion yen (roughly USD 9.6 billion) in a new HBM fab at its Hiroshima site, with the Japanese government expected to subsidise up to 500 billion yen of that capex. This is on top of earlier EUV-based DRAM investments that already enjoyed substantial support from Tokyo.

The United States, meanwhile, is deploying CHIPS Act subsidies to keep advanced memory capacity onshore, while tightening export controls that limit China’s access to cutting-edge memory and manufacturing tools. China is responding with its own subsidies and import-substitution push, but the technology gap and sanctions regime make this a long grind rather than a quick catch-up. For investors, this “policy premium” means that memory valuations will increasingly embed geopolitical risk as much as business fundamentals.

The obvious question—especially for anyone who has lived through prior memory booms—is whether AI demand can finally kill the industry’s famous boom-bust pattern. On one side, the demand story is compelling. Global AI spending is estimated at around USD 1.5 trillion in 2025 and is expected to cross USD 2 trillion as soon as 2026, according to recent analyses cited by the World Economic Forum. That kind of spending will not be possible without a commensurate rise in memory capacity, particularly HBM.

On the other side, the laws of capital cycles have not been repealed. Current shortages and sky-high margins are already triggering huge capex plans—from Micron’s Japan HBM fab to Korean and Chinese expansions. If all these projects come online around 2027–2028, just as AI hardware growth normalises, the industry could once again swing into oversupply. For now, the base case is that this “supercycle” lasts several years, but investors would be unwise to assume that structurally high memory margins are permanent.

For India, the AI memory crunch is both a threat and an opportunity. On the threat side, India is overwhelmingly a net importer of semiconductors, including all advanced memory. Higher DRAM and NAND prices will flow through into the cost of everything from smartphones and laptops to servers and networking gear. That matters in a country where electronics is one of the fastest-growing import categories and where the government wants to reduce dependence on overseas suppliers.

On the opportunity side, India is finally finding a foothold in the value chain. Micron’s assembly and test project at Sanand, Gujarat, is the first major global memory investment on Indian soil. The company plans to invest up to USD 825 million across phases, while the central government will cover 50% of total project cost and the state will add another 20% in incentives, taking the combined investment to about USD 2.75 billion. Phase one, with around 500,000 square feet of cleanroom space, is slated to become operational around 2024–2025 and is expected to create up to 5,000 direct jobs and 15,000 community jobs over time.

This is not a wafer fab; it is an ATMP (assembly, testing, marking, and packaging) facility. But in a world where HBM packaging and advanced testing are as strategically important as the memory die itself, that distinction matters less than it used to. If India can execute well on Micron’s project, it builds credibility to attract more packaging, OSAT, and eventually front-end manufacturing over the decade. The timing is favourable: global players want to diversify away from a China-centric supply chain just as India is offering aggressive subsidies and a large domestic market.

Indian IT services and engineering-R&D firms that design chips, boards, or AI infrastructure for global clients stand to gain as semiconductor and cloud companies ramp up spending on design, validation, and optimisation of memory-heavy systems. Domestic EMS and electronics manufacturers benefit as device makers localise more of their production to arbitrage rising bill-of-materials costs and to qualify for India’s production-linked incentives. Data-center operators and REIT-like structures could indirectly ride the wave of AI infrastructure build-outs, though they also face the headwind of higher equipment costs and the need to pass through those costs to customers.

For all the excitement, memory remains a cruel business, and AI does not magically erase cyclicality. If you buy into beneficiaries of today’s supercycle—whether foreign memory makers or Indian companies exposed to AI hardware—position sizing and risk management matter more than narrative. A plausible scenario in 2027–2028 is one where all the currently announced HBM and DRAM capacity comes online just as the first big wave of AI infrastructure build-out slows. In that world, the same operating leverage that looks magical on the upside becomes brutal on the downside.

Indian policy risk is another factor. Subsidy-driven projects like Micron’s Sanand facility depend on consistent execution, stable regulation, and predictable power, water, and logistics. Any slippage erodes India’s credibility as an alternative semiconductor hub. At the same time, India will have to navigate a delicate geopolitical balance between the U.S., which wants tighter controls on China-linked tech flows, and its own desire to stay non-aligned and open to multiple supply chains. For investors, this means treating semiconductor-linked themes as long-duration but high-volatility stories, where political economy is as important as financial modeling.

Ultimately, the AI memory crunch is a reminder that every technological revolution redistributes bottlenecks. The GPU was yesterday’s hero; memory is today’s pinch point. For Indian investors, the task is not to chase headlines about shortages, but to understand where enduring bargaining power will reside once today’s shortage gives way to tomorrow’s overcapacity. Those who get that call roughly right—across both global and Indian markets—will be the ones who truly remember this cycle.

Discover investment portfolios that are designed for maximum returns at low risk.

Learn how we choose the right asset mix for your risk profile across all market conditions.

Get weekly market insights and facts right in your inbox

It depicts the actual and verifiable returns generated by the portfolios of SEBI registered entities. Live performance does not include any backtested data or claim and does not guarantee future returns.

By proceeding, you understand that investments are subjected to market risks and agree that returns shown on the platform were not used as an advertisement or promotion to influence your investment decisions.

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Skip Password

By signing up, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with Password →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Log in with OTP →

By logging in, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy

"I was drawn to Wright Research due to its multi-factor approach. Their Balanced MFT is an excellent product."

By Prashant Sharma

CTO, Zydus

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

Answer these questions to get a personalized portfolio or skip to see trending portfolios.

(You can choose multiple options)

Investor Profile Score

We've tailored Portfolio Management services for your profile.

View Recommended Portfolios Restart